When I heard Junot Díaz read last spring, he mentioned how when he started writing he was “stealing from the writers I loved the best. I cold-mugged the books.” Cold-mugging your favorite writers — a fine literary tradition. Reading John Updike’s appreciation of William Maxwell, it was nice to learn this anecdote about Maxwell’s first novel, Bright Center of Heaven, which was first published in 1934 and later suppressed by the author on the grounds it was “stuck fast in it is period” and “hopelessly imitative.”

In a Paris Review interview, [Maxwell] said, “My first novel . . . is a compendium of all the writers I loved and admired.” Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse,” especially, is imitated in the drifting weave of action and interior reflection, and in the rhythms, paced by commas, of the long descriptive sentences. Ten years after the novel’s publication, he reread it and wrote, “I . . . discovered to my horror that I had lifted a character–the homesick servant girl–lock, stock, and barrel from ‘To the Lighthouse.’ ”

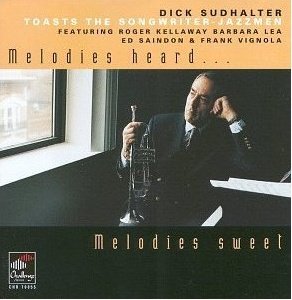

Dick Sudhalter wrote three of the most important books ever published about jazz and American popular music,

Dick Sudhalter wrote three of the most important books ever published about jazz and American popular music,  I knew that Dick wanted to die–he told me so while he still could–and so I suppose I should be glad that his suffering is now over. Yet I find it impossible to greet the news of his death with anything other than black sorrow, though I know that it will someday be a comfort to have his books to read and his records to play. When I heard that he was dying, I sat quietly in my hotel room for a few minutes, then opened up my iBook and listened to the sweetly elegiac performance of Duke Ellington’s “Black Butterfly” that he recorded with Roger Kellaway in 1999 (it’s on Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet). It isn’t given to very many of us to write our own epitaphs, much less play them, but I can’t think of a better way to sum up what Dick Sudhalter was all about than to listen to that song.

I knew that Dick wanted to die–he told me so while he still could–and so I suppose I should be glad that his suffering is now over. Yet I find it impossible to greet the news of his death with anything other than black sorrow, though I know that it will someday be a comfort to have his books to read and his records to play. When I heard that he was dying, I sat quietly in my hotel room for a few minutes, then opened up my iBook and listened to the sweetly elegiac performance of Duke Ellington’s “Black Butterfly” that he recorded with Roger Kellaway in 1999 (it’s on Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet). It isn’t given to very many of us to write our own epitaphs, much less play them, but I can’t think of a better way to sum up what Dick Sudhalter was all about than to listen to that song. Cape May Stage performs in a deconsecrated Presbyterian church whose ecclesiastical yet intimate air enhances the effectiveness of its superb production of “Doubt,” John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about a Roman Catholic priest (Paul Bernardo) who may or may not have molested a child in his care. I saw “Doubt” at what I took for granted would be a disadvantage, since Brían F. O’Byrne, Cherry Jones, Heather Goldenhersh and Adriane Lenox, the stars of the original New York production, gave bravura performances that still stand out in my memory. Imagine my surprise, then, when Mr. Bernardo, Mary Baird, Abby Royle and Sameerah Luqmaan-Harris, all of whose names are new to me, turned out to be every bit as good as their better-known predecessors….

Cape May Stage performs in a deconsecrated Presbyterian church whose ecclesiastical yet intimate air enhances the effectiveness of its superb production of “Doubt,” John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about a Roman Catholic priest (Paul Bernardo) who may or may not have molested a child in his care. I saw “Doubt” at what I took for granted would be a disadvantage, since Brían F. O’Byrne, Cherry Jones, Heather Goldenhersh and Adriane Lenox, the stars of the original New York production, gave bravura performances that still stand out in my memory. Imagine my surprise, then, when Mr. Bernardo, Mary Baird, Abby Royle and Sameerah Luqmaan-Harris, all of whose names are new to me, turned out to be every bit as good as their better-known predecessors….