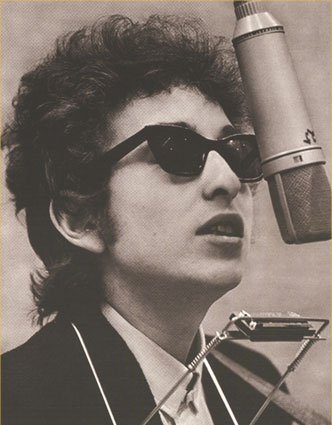

The big news in today’s Pulitzer Prizes is that Bob Dylan was honored with a special citation for “his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.” A little late, I’d say.

The big news in today’s Pulitzer Prizes is that Bob Dylan was honored with a special citation for “his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.” A little late, I’d say.

As for the other prizes awarded in the non-journalistic categories of “letters, drama, and music,” I can only speak with authority about the awarding of the drama prize to Tracy Letts’ August: Osage County, which was unquestionably superior to its competition. For what it’s worth, here’s what I wrote about it in The Wall Street Journal last year:

As an ardent supporter of Chicago theater, I’m overjoyed that one of that city’s best-known troupes has come east to strut its stuff: The Steppenwolf Theatre Company is performing Tracy Letts’s “August: Osage County” on Broadway. Mr. Letts’s new play is a 13-character, 3½-hour monster about the Westons, an Oklahoma family so dysfunctional that it’s a wonder they’re not all dead. Repeat after me: adultery, alcoholism, drug addiction, incest. One of them is even a poet!

No doubt it sounds like Tennessee Williams on a bender, but what makes “August: Osage County” so excitingly watchable is that Mr. Letts has (mostly) chosen to play these grim matters for laughs. The horrific family dinner at which Mom Weston (Deanna Dunagan) pops a double handful of downers and starts settling scores is a glittering piece of black comedy, and the cast, consummately well directed by Anna D. Shapiro, plays it to perfection. Ms. Dunagan and Amy Morton (who gives a commanding performance as Barbara, the oldest Weston daughter) will surely be remembered at Tony time, but everyone deserves a group award for ensemble acting above and beyond the call of duty.

There’s a catch, and it’s a huge one: The hour-long first act is a pretentious piece of superfluous exposition that could and should have been cut. I suppose I ought not to suggest that you come late (nudge, nudge), but if you do choose to see the whole thing, take my word that it gets better–a whole lot better–after the first intermission.

Is that the stuff Pulitzers are made of? I suppose so, though the drama prize has had a fairly impressive batting average in recent years. Anna in the Tropics, Doubt, and I Am My Own Wife all won–but, then, so, did the utterly unmemorable Rabbit Hole. August: Osage County isn’t a great play, but we don’t get many of those, and it’s a solid, exciting piece of work, so I’m not complaining.

As for the other non-journalistic awards, I haven’t read any of the books that won, nor had I heard David Lang’s The Little Match Girl Passion, which won the music prize. You can listen to it here, which I did after the prizes were announced this afternoon. (It’s pretty enough, but I wasn’t impressed.) Truth to tell, I hadn’t even heard of any of the winning titles, and I think of myself as being more or less culturally literate. I did read two of the finalists for the biography prize, Martin Duberman’s The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein and Zachary Leader’s The Life of Kingsley Amis, neither of which I thought prizeworthy, and one of the finalists for general nonfiction, Alex Ross’ The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, a brilliant and important book which I reviewed with the utmost enthusiasm in Commentary last year. (Alex’s blog is here.)

All of which says…what? Not very much, I fear. Nor are the Pulitzers nearly as important, culturally speaking, as they used to be, though they continue to ensure that their winners will be mentioned at least once in every major newspaper in America, which beats hell out of a sharp stick in the eye. Still, I doubt that this year’s winners will get much more traction in the media after the ink has dried on their citations, since American newspapers are increasingly turning their backs on high-culture coverage of all kinds. I wonder, for instance, what percentage of the papers that will be announcing the victory of John Matteson’s Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father in tomorrow morning’s editions bothered to run a review of the book when it was published.

Incidentally, one Michael S. Malone informed the world the other day that my blogging ought to receive a Pulitzer Prize for cultural criticism. Alas, it was all too plain to see that he was using me, Matt Drudge, Arianna Huffington, Mickey Kaus, Markos Moulitsas, Glenn Reynolds, and Michael Yon (talk about mixed company!) as sticks with which to beat the Old Media. This had the inevitable effect of diluting his compliment: “On Tuesday, the Pulitzer Prizes will be announced. And if they are anything like last year, the journalism awards will go to the usual collection of dying newspapers…There will be the usual flurry of media, and then those newspapers will go back to dying.”

Needless to say, the Pulitzers in journalism are for newspapers, not blogs (or magazines or radio documentaries, for that matter). And if I ever win one, it will presumably be for my work as a newspaperman, which takes up most of my time and energy. I love blogging, but I get paid to write for The Wall Street Journal, and far more people read me there than on “About Last Night.” Yes, the newspaper business is in trouble–bad trouble–but it isn’t dead yet.

At the same time, though, I wouldn’t dream of denying that precious few newspapers (mine fortunately excepted) are doing their duty, or anything like it, to high culture in America and the world. Which is why it strikes me as faintly hypocritical that they should continue to devote one day out of the year to praising a playwright, a composer, and a half-dozen writers–and Bob Dylan, who needs a Pulitzer Prize a lot less than the Pulitzer Prizes need Bob Dylan.

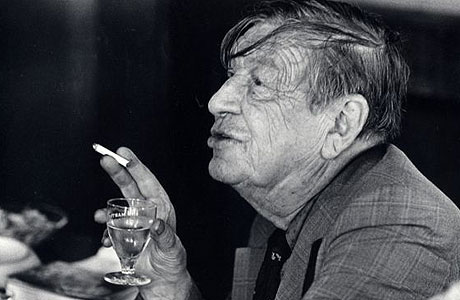

Would it be too outrageously immodest to request that an aria you had written be sung at your own funeral? No more so, surely, than the last musical request of W.H. Auden, an opera buff with a sense of humor: “When my time is up, I want Siegfried’s Funeral March and not a dry eye in the house.” (He got his wish.) Alas, our aria is a bit too dramatic to be wholly appropriate to such an occasion. It would be nice to have one of Paul’s pieces played, though, and I can think of two songs that would be just as appropriate, Copland’s “The World Feels Dusty” (from

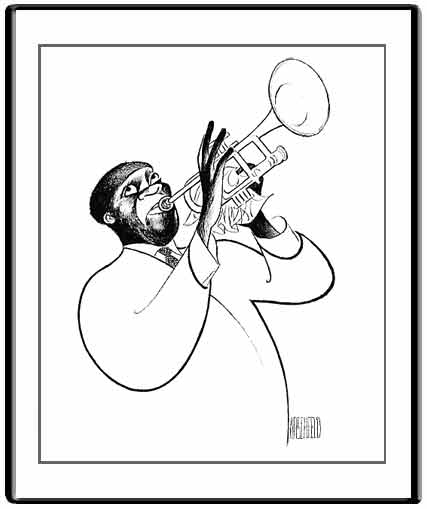

Would it be too outrageously immodest to request that an aria you had written be sung at your own funeral? No more so, surely, than the last musical request of W.H. Auden, an opera buff with a sense of humor: “When my time is up, I want Siegfried’s Funeral March and not a dry eye in the house.” (He got his wish.) Alas, our aria is a bit too dramatic to be wholly appropriate to such an occasion. It would be nice to have one of Paul’s pieces played, though, and I can think of two songs that would be just as appropriate, Copland’s “The World Feels Dusty” (from  Needless to say, I couldn’t imagine departing this life without the assistance of Louis Armstrong, who in 1950 obligingly made a wonderful recording called

Needless to say, I couldn’t imagine departing this life without the assistance of Louis Armstrong, who in 1950 obligingly made a wonderful recording called  •

•  • The death of Gene Puerling has yet to attract the attention of the increasingly culturally illiterate New York Times, but the

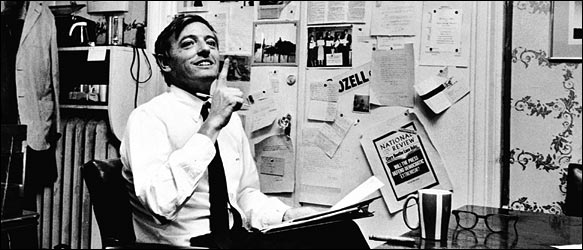

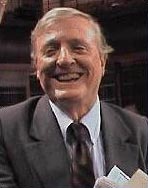

• The death of Gene Puerling has yet to attract the attention of the increasingly culturally illiterate New York Times, but the  It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love.

It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love. Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar.

Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar. “South Pacific” goes dead in the water every time the characters stop singing and start talking, which is way too often. The book, adapted by Hammerstein and Joshua Logan from James Michener’s “Tales of the South Pacific,” is a wartime drama built around a May-September romance between Nellie Forbush (Ms. O’Hara), a cheery Navy nurse, and Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot), a super-suave French plantation owner who fled to a Polynesian island after killing a man, took up with a now-deceased native woman and sired an adorable pair of children. Their skins, alas, are too brown to suit the Arkansas-born Nellie, and thereby hangs the tale of “South Pacific.” Will true love purge our poor benighted heroine of her racism? Will her middle-aged suitor be killed in a daredevil mission behind Japanese lines? Would that one could care, but Hammerstein preaches his sermon with head-thumping triteness: You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late/Before you are six or seven or eight/To hate all the people your relatives hate. Stir in a megadose of beat-the-Japs period fervor, and you get a show so reeking of uplift that you can all but feel your pulse slowing to a crawl as the second act inches toward its predestined happy ending.

“South Pacific” goes dead in the water every time the characters stop singing and start talking, which is way too often. The book, adapted by Hammerstein and Joshua Logan from James Michener’s “Tales of the South Pacific,” is a wartime drama built around a May-September romance between Nellie Forbush (Ms. O’Hara), a cheery Navy nurse, and Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot), a super-suave French plantation owner who fled to a Polynesian island after killing a man, took up with a now-deceased native woman and sired an adorable pair of children. Their skins, alas, are too brown to suit the Arkansas-born Nellie, and thereby hangs the tale of “South Pacific.” Will true love purge our poor benighted heroine of her racism? Will her middle-aged suitor be killed in a daredevil mission behind Japanese lines? Would that one could care, but Hammerstein preaches his sermon with head-thumping triteness: You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late/Before you are six or seven or eight/To hate all the people your relatives hate. Stir in a megadose of beat-the-Japs period fervor, and you get a show so reeking of uplift that you can all but feel your pulse slowing to a crawl as the second act inches toward its predestined happy ending.