My review of David Mitchell’s Black Swan Green appeared in last weekend’s Baltimore Sun. I loved it, here’s why:

The time is 1982 in the English Midlands, the era of Margaret Thatcher, Chariots of Fire, the Falklands War, and Talking Heads. Jason Taylor is about to turn 13 when the novel opens, and at the mercy of the mob of Wilcoxes, Redmarleys and Broses. In an adolescent jungle where hardness reigns, Jason is heartbreakingly soft. He’s plagued by a capricious stammer he personifies as an inner villain called Hangman, who wreaks gleeful havoc with his confidence. He doesn’t know what certain popular epithets favored by his peers mean and is afraid to ask. He unfashionably cares about people, beauty, and, worst of all, poetry. If his peers knew this, he recognizes, “they’d gouge me to death behind the tennis courts with blunt woodwork tools and spray the Sex Pistols logo on my gravestone.” So he writes poems under a pseudonym and publishes them in a local journal.

It’s convenient for Mitchell that Jason is a budding poet and an instinctive naturalist to boot, a sort of English Wendell Berry in the making. Jason’s poetic leaning makes plausible all kinds of verbal flourishes and fine observations that might otherwise be a stretch coming from a 13-year-old. But Mitchell takes the liberty and makes the most of it; in fact, one of the most striking and beautiful things about his novel is the entirely plausible and disarming way in which Jason’s voice blends the resourceful and calibrated expression of a poet – “some way-too-early fireworks streaked spoon-silver against the Etch-A-Sketch gray sky” – with the occasionally colorful but essentially rote slang favored by a kid. The rich hash that results is, on just about every page, ordinary and extraordinary and ravishing.

Though Mitchell is best known for his previous novel, Cloud Atlas, he began building a following with his earlier books Ghostwritten and Number Nine Dream. Black Swan Green both cements and complicates his reputation as a painstaking formalist and a writer’s writer. On one hand, it is narrated more traditionally than any of the previous works, and dwells, more conventionally, on the inner life of a single character. Black Swan Green is an unapologetically realist novel and a hugely satisfying one. On the other hand, for all the naturalism of its effect, the book is every bit as elaborately stitched together as Mitchell’s more formally showy books. It has intricate patterns to reveal that might not surface on a first reading.

The whole thing can be read here. As you see, I found the novel generally excellent. But it also found an inside track to my heart in its preoccupation with Alain-Fournier’s enigmatic 1913 wonder of a novel Le Grand Meaulnes–a book that, if read at the right age, permanently enters the bloodstream. I read it as a high school senior, which seems to have been just young enough. Reading Alain-Fournier’s and Mitchell’s novels together would be a very cool small-scale reading project for the summer, no matter one’s age.

For a smart dissenting view on Mitchell’s novel, see Jenny Davidson’s generous-minded but ultimately lukewarm assessment at her blog Light Reading.

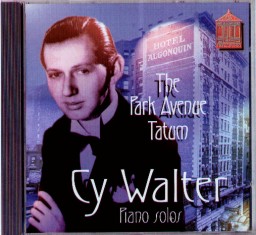

Walter recorded extensively from the Forties on, but until now none of his albums had ever been reissued, meaning that his name is virtually unknown today save to those lucky New Yorkers who once upon a time heard him live. Now Shellwood, an independent record label in England, has produced the first Cy Walter CD, a compilation of the pianist’s Liberty Music Shop 78s called The Park Avenue Tatum. All twenty-eight tracks are show tunes, among them “Begin the Beguine,” “Body and Soul,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Liza,” “‘S Wonderful,” and medleys from such half-remembered Broadway shows as Jerome Kern’s Very Warm for May, Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie, and Richard Rodgers’ By Jupiter.

Walter recorded extensively from the Forties on, but until now none of his albums had ever been reissued, meaning that his name is virtually unknown today save to those lucky New Yorkers who once upon a time heard him live. Now Shellwood, an independent record label in England, has produced the first Cy Walter CD, a compilation of the pianist’s Liberty Music Shop 78s called The Park Avenue Tatum. All twenty-eight tracks are show tunes, among them “Begin the Beguine,” “Body and Soul,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Liza,” “‘S Wonderful,” and medleys from such half-remembered Broadway shows as Jerome Kern’s Very Warm for May, Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie, and Richard Rodgers’ By Jupiter.