“I am resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change, but I am determined to understand what’s happening, because I don’t choose just to sit and let the juggernaut roll over me.”

Marshall McLuhan, “This Hour Has Seven Days”

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“I am resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change, but I am determined to understand what’s happening, because I don’t choose just to sit and let the juggernaut roll over me.”

Marshall McLuhan, “This Hour Has Seven Days”

I reviewed the Public Theater‘s Shakespeare in the Park production of Henry V, directed by Mark Wing-Davey and starring Liev Schreiber (who is really, really good), in this morning’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s the money graf:

“Up until the war scenes proper, all the energy of this production is comic, with Mr. Schreiber the only straight face on stage. Everybody else is trying to get laughs by any means necessary. Even the low comedians are painted with a too-wide brush: Bronson Pinchot’s Pistol is a pompadoured idiot with a Tony Curtis-type Lawng Oyland accent whom we find amusing himself in a latrine, a girlie magazine in his free hand. The fact that so much of the slapstick is clever (though not that particular bit) only makes matters worse. By the time intermission rolled around, I felt as if I’d been watching an old friend skinned alive by a stand-up comedian who told really funny jokes as he wielded the knife.”

No link, alas, but the “Weekend Journal” section of the Friday Journal is definitely worth a buck, with or without me.

This exchange with Paul Johnson, author of Modern Times, was posted yesterday on National Review Online’s “The Corner.” (Several writers, myself included, were recently invited to supply questions for Johnson to be asked on a PBS show called Uncommon Knowledge. This is from the transcript–the show hasn’t aired yet.)

Q. Terry Teachout asks–

A. I know Terry Teachout. He’s a wonderful writer, especially on music.

Q. Terry would like to know if Paul Johnson has a favorite painting by Norman Rockwell.

A (after a long silence while he thinks). The one of the barbershop. All of his paintings are interesting and good and a lot of them are funny. But that is one which clearly has the right to be called a considerable work of work. The actual structure of the painting is marvelous.

The painting in question, by the way, is “Shuffleton’s Barber Shop,” and I agree.

A reader writes:

How does one go about discovering gems like your new Marin etching? I am just starting out and would like to replace my college-era posters with something more enduring, but I have absolutely no clue how or where to look for such things. I have contemplated purchasing several pieces in the past, but I find art galleries imposing and a little bit scary. How does one learn how to buy art? And how does one know if the prices are inflated? Sorry to burden you with such an odd request, but I can’t be the only one who is afraid to embark on this enterprise.

Nothing odd about it. I felt the same way when I first started going to galleries, though I think in my case it arose from a fear of looking dumb, coupled with the reflexive embarrassment that Midwestern WASPs feel at the thought of discussing money with strangers. But as Anthony Powell wrote in A Question of Upbringing, “Later in life, I learnt that many things one may require have to be weighed against one’s dignity, which can be an insuperable barrier against advancement in almost any direction.” The first step in the process of smashing through that barrier is screwing up your courage and saying to the ominous-looking person in charge, “Uh, what does that pretty purple-and-blue one cost?” Once you do this, you will have lost your virginity and can proceed at will. It only hurts the first time. Very often–though not always–you will quickly discover that the folks who run galleries are nice, helpful human beings who wouldn’t dream of embarrassing a potential customer. (Many galleries, by the way, have printed price lists of the works on display at the front desk. Ask.)

Are the prices inflated? Sometimes. How do you know? You don’t. That’s why God made computers. The Internet is without question the most valuable educational tool available to budding young art buyers, especially if you’re looking (as you should be) for “multiples,” meaning works of art which exist in multiple copies, i.e., etchings, woodcuts, or signed limited-edition lithographs and screenprints. Galleries dealing in multiples can be found in most major cities, and many of them also have Web sites. A good Web site features thumbnail images of the pieces in a gallery’s inventory (which can usually be enlarged). Most of the time it also includes prices, and if it doesn’t, all you have to do is send the gallery an e-mail asking for the price of a specific piece, which is less anxiety-inducing than asking in person. Once you’ve spent a few Web-browsing sessions engaged in competitive shopping, you’ll start to get a feel for whose prices are inflated and whose aren’t. Generally speaking, the Web has helped to bring on-line prices into broad accord, but I was looking for a particular Helen Frankenthaler screenprint last month and discovered that there was a $3,000 difference in price between the least and most expensive copies. (Guess which one I bought?)

Don’t buy art until you’ve looked at quite a bit of it, both off and on line, and know which artists speak to you most persuasively. The trick is to reconcile your tastes with your budget. I’m interested in American art, not only because I like it but because much of it is still affordable (also, there are a whole lot of phony European art prints out there). Many fine 19th- and 20th-century American artists have made prints of various kinds. Start looking, and see what you like best. Read art books. Use Google, searching for both the artist and the medium that interests you. I found my Marin etching by searching for “John Marin” and “etching.” Another useful code phrase is “fine prints,” which often (but not always) appears on the Web sites of galleries. Remember that inventories turn over, so don’t assume that just because you can’t find what you’re looking for this week, you’ll never be able to find it. Be patient.

What about eBay, you ask? Well, I’ve bought a couple of lovely pieces there, but I can’t recommend it to the novice buyer, simply because you don’t yet know enough to know whether you’re getting (A) an amazing bargain or (B) screwed. I came away clean both times, but I already knew a lot about the artists in question (Nell Blaine and Neil Welliver). Much better to stick to galleries until you find your footing.

Buying art on line isn’t nearly as risky as it sounds. Reputable dealers typically belong to the International Fine Print Dealers Association (whose Web site is a good place to start learning about prints) and advertise that fact on their sites. The more extensive and well-designed the site, the more likely the dealer in question has been around for a while. If you really want to play it safe, which is perfectly all right, the Metropolitan Museum of Art publishes and sells signed limited-edition prints on its Web site. I bought my first piece from them. You should also look at Crown Point Press, a much-admired publisher of prints by a wide assortment of American artists. Both of these sites are completely up front about pricing. Visit them and you’ll start to learn what things cost. In recent months, I’ve also bought from Jane Allinson, Rona Schneider, Flanders Contemporary Art , and K Kimpton , all of whom have good Web sites and are a pleasure to deal with. Tell them I sent you.

Tyler Green writes:

There is a whole room of Morandi up at Washington’s Hirshhorn Museum right now as part of their permanent collection show, “Gyroscope.” It’s a large, cavernous, dark room with no natural light. Each wall is about 20-25 feet long…and has just one tiny, precious, divine Morandi on it. It’s a heckuva installation.

I’m there, baby. What time does the next Metroliner leave?

P.S. Jazz singer Kendra Shank writes to say that she liked Karen Wilkin’s quote about Morandi: “For anyone who pays attention, the microcosm of Morandi’s tabletop world becomes vast, the space between objects immense, pregnant, and expressive.” She adds that “the same could be said about Shirley Horn‘s singing.” Could it ever….

“Art, and the summer lightning of individual happiness: these are the only real goods we have.”

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts

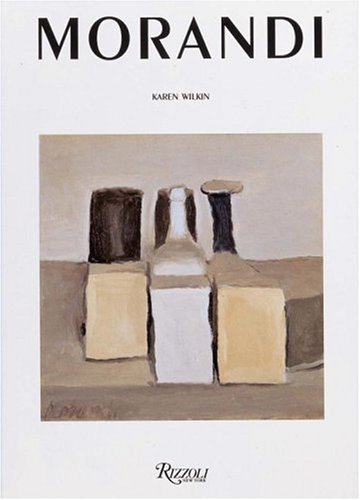

A couple of months ago, I hung a poster over my front door, a reproduction of a still life consisting of three boxes, a cup, and a jug, all floating in a neutral-colored void. The painter’s name appears nowhere on the poster, which came from a still-life show at Washington’s Phillips Collection, my favorite museum. Ever since I put it up, at least one visitor per week has asked me who did the painting. You wouldn’t think so plain an image would attract so much attention–I have far more eye-catching items on my walls–but there’s something about it that speaks to a certain kind of person.

Not to keep you in suspense, but the painting in question is a 1953 oil by Giorgio Morandi called, simply, “Still Life.” Most of Morandi’s paintings are called “Still Life.” He was born in Bologna, Italy, in 1890, and died there in 1964, and he spent most of his seemingly uneventful life arranging and rearranging a dozen or so boxes, cups, jugs, bottles, and pitchers on a tabletop, and painting them over and over again. Sometimes he made etchings of his carefully arranged objects, and from time to time he painted a landscape. That’s about all there is to say about him, really, except that he was a very great artist, which is more than enough to say about anybody.

Not to keep you in suspense, but the painting in question is a 1953 oil by Giorgio Morandi called, simply, “Still Life.” Most of Morandi’s paintings are called “Still Life.” He was born in Bologna, Italy, in 1890, and died there in 1964, and he spent most of his seemingly uneventful life arranging and rearranging a dozen or so boxes, cups, jugs, bottles, and pitchers on a tabletop, and painting them over and over again. Sometimes he made etchings of his carefully arranged objects, and from time to time he painted a landscape. That’s about all there is to say about him, really, except that he was a very great artist, which is more than enough to say about anybody.

What makes Giorgio Morandi’s paintings so special? To begin with, most people don’t seem to find them so. Though Morandi is renowned in his native Italy, he is unknown in this country save to critics, collectors, and connoisseurs. It’s easy to see why. His art is too quiet and unshowy, too determinedly unfashionable, to draw crowds. It creates its own silence. “Curiously, these deceptively modest paintings, drawings, and prints seem to elicit only two responses: extreme enthusiasm or near-indifference. And yet, this is not surprising, since Morandi’s art makes no effort to be ingratiating or to put itself forward in any way….For anyone who pays attention, the microcosm of Morandi’s tabletop world becomes vast, the space between objects immense, pregnant, and expressive.”

That quote is from Karen Wilkin’s Giorgio Morandi. Wilkin is one of America’s finest art critics (as well as a damned good freelance curator), and her profusely illustrated monograph makes the case for Morandi far better than I could ever hope to do. What I wish I could do is tell you to go right out today and look at a dozen Morandis, but you can’t, unless you happen to live in Bologna, in which case you can go to the Museo Morandi and look at them to your heart’s content. Most major American museums in America own a Morandi or two, and sometimes they even hang them. The Phillips often has one of its two oils on display, and in recent months I’ve seen Morandis in Princeton and St. Louis. But I’ve never seen one in New York, except for the reproduction in my living room. Somebody in this country is collecting them–Morandi’s etchings are way out of my modest price range–but it clearly isn’t MoMA or the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Barring a quick side trip to Bologna or Washington, your best bet is to purchase a copy of Giorgio Morandi. I’ve given away several copies as presents. Only last week, I gave one to a friend who noticed my Morandi poster and asked about it. Should that ring the bell, you can buy a poster of your own. You will then be officially enrolled in the International Society of Morandi Fanatics. We don’t have meetings–we just trade occasional e-mails about what’s hanging where. Feel free to advise me about domestic Morandi sightings. And if any of my wealthy readers are feeling moderately generous, a gift of a Morandi still-life etching would not go unappreciated.

A reader invited me to post “some words on your working life as a critic.” To this end, he submitted the following questionnaire:

Does having to write about something ever diminish the pleasure you take from it? No, but knowing I have to write about it first thing tomorrow morning sometimes does. Taking notes at a performance takes away part of the fun, so I try to do it as infrequently as possible.

Do you read, listen to music, sitting, lying down? I read lying down and listen sitting up.

Do you write in the morning, evening? Full, empty stomach? Take coffee? I usually start writing shortly before the deadline. Prior to Monday, I generally managed not to write at night (at least not very often), but that went out the window as soon as this blog went live. Stomach contents don’t seem to matter. Except for the odd mocha frappuccino, I rarely drink coffee other than to be sociable.

Do you ever work in an, ahem, merry state? Surely you jest, sir!

Do you worry, prolific as you are, that you won’t get all around your subject? Jeepers, why worry? Nobody ever gets all around his subject, least of all me.

Do you, did you ever consciously imitate any style? Oh, Lord, yes. In fact, I once wrote an essay about this very subject, which will be reprinted in A Terry Teachout Reader, out next spring from Yale University Press.

Who are your critical influences? Originally Edmund Wilson, more recently Edwin Denby, Joseph Epstein, Clement Greenberg, and Fairfield Porter. I would be happy to be a tenth as good as any of them.

What do you try to do in a review? Not to be cute, but I try to write pieces that are (A) cleanly written enough not to give my editors any unnecessary trouble and (B) personal enough that they sound like me talking. Beyond that, I leave it to the muse.

Do you have an idea of what you’re going to write before you do it? Usually, but rarely more than the title and the first few sentences. On occasion, though, I just sit down and wing it. (So far as I know, by the way, there’s no correlation between the length of time I spend writing a piece and its quality.)

How many words a day? It depends on what’s due. If absolutely necessary, I can manage 2,500 polished words between sunrise and bedtime. In the immortal words of James Burnham, “If there’s no alternative, there’s no problem.” But I try not to write that much in a single day. It’s not exactly compatible with having a life.

Do you revise? Endlessly–but I hope it doesn’t show.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

An ArtsJournal Blog