In an era of growing political impunity, when dissidents are murdered on foreign soil and even the head of Interpol is not immune from being “disappeared”, Ma Jian seems almost recklessly brave. Could there be a more provocative title than that given by the exiled novelist to his latest satirical onslaught on the country of his birth? For, with China Dream, he co-opts the rhetoric of the Chinese leader Xi Jinping to tell the story of a politician who is driven mad by memories of his own corruption.

Xi first used the phrase shortly after becoming general secretary of the Communist party in 2012, and Ma has responded “in a rush of rage” with a short, ferocious novel about the way turbo-capitalism and authoritarianism have combined to inform a Chinese dream that excludes all but a chosen few. “I wanted to give myself the challenge of encapsulating everything in as few words as possible,” he says, wryly adding that it will be interesting to see how the Chinese authorities react to the novel, given that they’ve outlawed so many “key words” online – “even the name Winnie-the-Pooh is banned because people joked that Xi Jinping resembled him”.

A momentary silence falls as we consider the surreal possibility of the “paramount leader” being forced to ban his own slogan. But the reality, Ma acknowledges, is that censorship is now so all-encompassing that the novel will very probably not be allowed to exist in Chinese, even in Hong Kong, which has historically provided a toehold for work by dissident authors banned on the mainland.

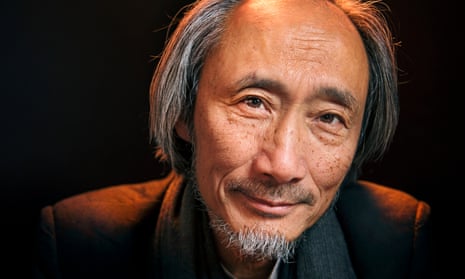

In a tranquil London cafe, close to the home he shares with his translator and partner Flora Drew and their four children, the risks this slight, 65-year-old writer is taking are hard to comprehend. Despite living in the UK for 17 years, he does not speak English. It’s not as if he hasn’t tried, says Drew, who translates our interview, but he has a stubborn devotion to his mother tongue and remains more engaged with goings-on in China than those in his adopted country. “Living in the west allows me to see through the fog of lies that shrouds my homeland,” he writes in the foreword to China Dream. During the interview, he invokes Dante’s Divine Comedy: “It’s only through being expelled that the poet gets to see heaven and hell and purgatory.”

It was a perspective forced on him from his earliest days, as one of five children born into a well-to-do family in the provincial city of Qingdao in 1953. A childhood in which he had already shown promise as an artist came to an abrupt end with the start of the Cultural Revolution. He was 13 years old. His art teacher was persecuted as a “rightist” and his grandfather, a landlord and tea connoisseur, was executed. At 15, he joined an arts propaganda troupe, beginning an adult life that would take him through various industrial assignments to a job as a photojournalist. He married a dancer and had the regulation single child. Then a photography prize brought him to the attention of the authorities and he was transferred to work for the foreign propaganda unit of the Federation of Trade Unions in Beijing.

There, living in a “one‑bed shack”, he connected with a buzzy young community of writers and artists. Officially, he worked as a journalist. Unofficially, he made and occasionally sold paintings. “Mostly they were stolen, but a man from the US embassy bought one for $40,” he recalls. “My hair was encrusted with oil paint and the walls were papered with my paintings.”

In 1983, just as he turned 30, he hit the crisis that would upend his life. Divorced from his wife, who forbade him to make contact with his daughter, he was arrested for “spiritual pollution”. Though Ma was released, his shack was ransacked and his canvases ripped up. “I never painted again,” he says. “I saw what a fragile medium it was, and how vulnerable to abuse and persecution, and I asked myself what was I going to do for the rest of my life?”

In his attempt to answer this question he converted to Buddhism and set off on a three-year journey across China on foot. At first, he was afraid even to record what he witnessed in his notebook, in case it fell into the wrong hands, but gradually, he says, “I saw that through literature I could paint my own reality. I could record history.”

He arrived in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa to find a people whose traditions had been corrupted by poverty and political oppression even as they celebrated the 20th anniversary of their “liberation” to the status of autonomous region. In 1987, Ma poured his impressions into a collection of short stories, belatedly published in English as Stick Out Your Tongue. It was immediately banned by the Chinese censors, sending him into an exile from which he has never permanently returned, though until six years ago he was allowed to visit China, and continues to keep in close contact with friends and family.

He turns up for the interview with a dramatically bandaged thumb, the result of an accident while building a shed in his garden, the explanation of which leads on to one of his latest frustrations. He had written a letter to one of his brothers inviting him to come over to help, he says, “but during this time there was a huge demo of disgruntled veterans demanding higher benefits, so the whole town had been sealed off and surrounded by armed police. No information was able to get in or out, so the letter has probably been handed over to the authorities. What happened there shows how today’s China is more extreme than anything George Orwell could have imagined, because these events don’t even reach public consciousness: it’s as if they never happened.”

It is not only China that troubles Ma today. “The world is becoming increasingly unsafe,” he says. “Just look at what happened to Jamal Khashoggi: within the space of seven minutes we saw the triumph of barbarism over civilisation. But this is happening every day in China. Everyone thought we could ignore what happened in 1989 [the Tiananmen Square massacre] and that economic expansion meant it would become increasingly like the west, but that has been a catastrophic miscalculation. China might have draped itself in a coat of prosperity, but inside it’s become more brutal than ever, and it’s this venomous combination of extreme authoritarianism and extreme capitalism which has infected countries around the world.”

Erasure of memory is the abiding theme of Ma’s work, whether through the literal motif of an unconscious man in his epic 2008 novel Beijing Coma, set around Tiananmen Square, or through the allegorical pursuit of a recipe for “Old Lady Broth of Amnesia” to which the municipal leader Ma Daode devotes himself in China Dream, tormented by a past in which he drove his own parents to suicide by denouncing them. “The process of dragging back memories that are being constantly erased, especially from my position of exile, makes even more important to me the primacy of memory,” Ma says, “and how it not only involves a nation’s sense of history but a person’s sense of self.”

His satire is always firmly located in violations of the human body. Stick Out Your Tongue told stories of ritual rape and multi-generational incest. In his 2013 novel, The Dark Road, aborted late-term foetuses are carried around in plastic bags or boiled in Cantonese restaurants to make potency soups for men. The fourth of China Dream’s seven episodes takes Ma Daode to a strip club, where VIPs have orgies in Mao’s private room with women who are identified only by numbers. The reason for this, he explains, is because “totalitarianism not only seeks to control the thought but also the body in which those thoughts are housed”.

“As a writer, when you are trying to describe your characters, there’s a visceral connection to their being. But in my exploration of the body I’m always trying to show that in these systems, when a regime is trying to hurt a person’s physical being, at the heart of it is an attempt to crush their soul. Sometimes, the body can survive but a lot of the time it becomes no more than a carcass.”

Red Dust, his semi-fictionalised 2001 account of his life-changing three-year journey, introduced another persistent theme, betrayal. It recounted how he was twice betrayed by an actor girlfriend, whom he, in turn, considered denouncing to the film studio that employed her, out of jealousy over her infidelity. None of his characters is without blame, but neither are they entirely evil. Even Ma Doade in China Dream attempts to warn protesters that they will be killed if they refuse to move out when bulldozers arrive to clear their homes for redevelopment.

Ma relates his story quietly and urgently through Drew, keeping his own record of the conversation in spidery Chinese script. The couple met in 1997 when she was working on a TV documentary about the handover of Hong Kong to China and he was one of the few local people who agreed to speak. He invited her to a poetry reading and gave her all his books to read; she stayed on to finish them, and by the time she left they were together. He moved briefly to Germany after the handover before joining her in London. She has translated everything he has written since. Does she worry that his repeated attacks on China may put him in danger? “This is the first time I’ve felt concerned, because there’s a brazenness to the behaviour now and they can do it without any backlash at all,” she says.

But the couple have kept faith with the best of the country, sending their 15-year-old son to study martial arts at a Shaolin monastery and to spend time with his Chinese family. Ma plans to travel to the Hong Kong literary festival this month, to present his novel in English. “I refuse to be afraid,” he says. “The disregard for truth is infectious. It also explains the rise of Trump. We need to protect concepts of humanity, and freedom can’t be taken for granted. We have to remain constantly vigilant. The more you buckle under these pressures, the huger the monster becomes. One’s responsibility as a writer is to be fearless.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion