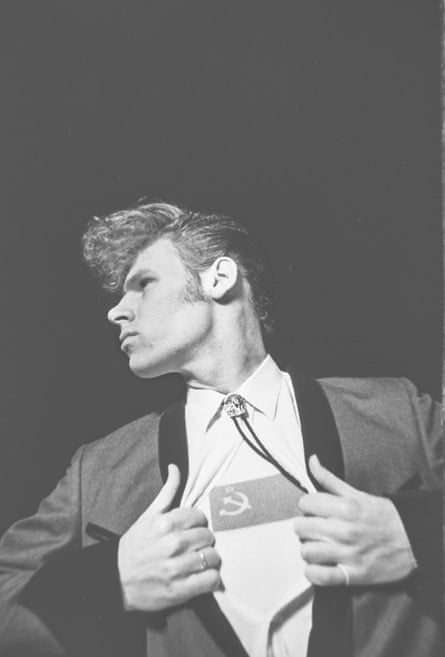

Hello. My name is Mark Kermode. I play skiffle. And I am not ashamed.” According to the BBC’s website, that statement was one of “eight moments that defined the Folk awards 2017”. The glitzy ceremony had been staged at London’s Royal Albert Hall and featured performances by such notables as Billy Bragg, Al Stewart, Ry Cooder and Shirley Collins. I knew Billy was a hardcore skiffle devotee, but I’d been more surprised to hear Al Stewart announce “I love skiffle!” while receiving his lifetime achievement award. Suddenly, it seemed, everyone was jumping on the skiffle bandwagon, although some of us had been aboard longer than others.

Like so many people, I started playing skiffle by accident. At the age of about seven or eight, long before I started trying to build my own electric guitar, my brother Jonny and I formed a skiffle band in our back garden in Finchley. Since Jonny is a couple of years younger than me, it’s probably fair to assume that the whole thing was my idea and he just got corralled into cooperating. But that’s not how I remember it. In my mind, we both simultaneously decided to stop messing around with bikes and Action Men and do something more expressive, more creative. Like forming a band.

It wasn’t a “band” in the traditional sense – we didn’t have any musical instruments and, even if we did, neither of us would have been able to play them. Instead, we got an old trestle table out of the garage at the end of the garden and covered it in kitchen implements (pans, colanders, metal draining racks etc) which made a loud noise when struck with a wooden spoon.

If you’d asked us what we were playing, we wouldn’t have known it was called skiffle. All we knew was that it was a joyous racket and that all our “instruments” would have to be returned to the kitchen before we could have our tea.

Inspired by American jug-bands, who would use bath-tubs, cooking jars and washboards to conjure up raucous jazz and blues, skiffle was a forerunner of rock’n’roll with a wonderfully inclusive DIY ethos. Crucially, no matter how talented the musicians were, the underlying message was: anyone can play these songs and you don’t need proper training or fancy instruments to do so. All of which made it the perfect medium for two under-10s from Finchley to spread their fledgling rock wings.

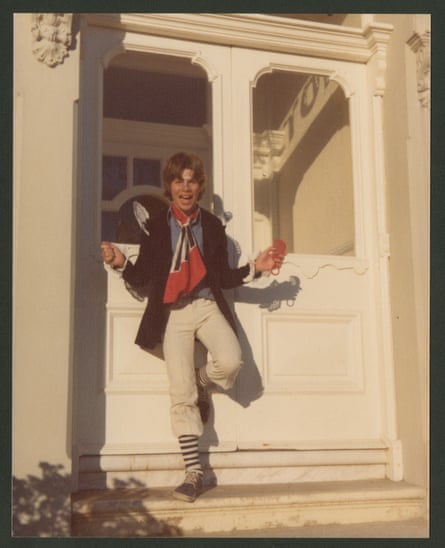

It was at the Edinburgh festival in the mid-80s that I really got the skiffle bug. At university in Manchester, having grown tired of playing guitar in noisy rock bands and performing unfunny standup musical comedy – I’d started to redirect my energies towards theatre. Most of the cool people I knew were either drama students or people who wished they were drama students. I fell into the latter category.

Having no discernible talent as an actor, I had somehow managed to reinvent myself as a “musical director” – this despite the fact that I could neither read music nor direct, let alone do both at the same time. I had convinced myself that my future lay in theatre and even started wearing a hat (a battered old brown trilby) on the basis that it felt… theatrical. (I have always been a bit of an arse.)

This brought me to The Death of Joe Hill, a prize-winning student play by upcoming Liverpudlian writer John Fay. Based on the life of the “Wobbly” activist and songwriter, The Death of Joe Hill had loads of musical numbers like The Preacher and the Slave and Casey Jones, all of which could be knocked out on an acoustic guitar which I played from the side of the stage – still wearing the hat. When the play went to the Edinburgh fringe, it was described by one reviewer – disparagingly, I think – as having an “off the back of a lorry” flavour.

At some point in the middle of the Joe Hill run, I met Alison Armstrong-Lee. Introduced to me as “the Queen of the Washboard”, Al, who was from Belfast, had taught herself to make a fantastic din with nothing more than a portable domestic appliance, some gardening sticks and a rubber band. She brandished her washboard as if it were a weapon, exuding rocking confidence as she bashed her way through any song you wanted to play. Al had been trying to put a band together with a singer and guitarist I knew from Manchester called Matt O’Casey who owned a battered Martin acoustic that had once been played by BB King.

Together with two of the actors from Joe Hill (Olly Fox, who played clarinet and John Preston, a trumpet player), I had spent several afternoons in Edinburgh trying to drum up support for the show by playing songs on the pavements around town. We soon decided it would be better to do the same thing in support of our own pockets as proper buskers. So we teamed up with Al and Matt, figured out five songs that we could busk our way through, and took to the streets.

The results were impressive. Although our first set was necessarily short, we managed to make about 10 quid in loose change. By the time we had to pack up and head for the theatre to do the evening performance of Joe Hill, we’d made around 40 quid. There was a problem, however. In the course of the afternoon, I had broken every single string on the acoustic guitar I was using.

This was to prove an ongoing issue. Having never been a light-handed player, my tendency to hit “all the strings all the time” was only worsened by the demands of playing outdoors. Somehow I had got it into my head that simply hitting the strings harder would make them louder. In fact, the volume of a guitar is defined by the resonance of the instrument rather than the force with which the player attacks the strings. You have to pluck, strum and generally fondle the notes out of the guitar, something which requires a level of musical skill which I lacked then and still lack today.

It wasn’t until we were back in Manchester and regularly losing money, thanks to my ability to break strings as fast as I could put them on the guitar, that we started to think I was probably playing the wrong instrument. While busking in Edinburgh, we’d seen a rockabilly band draw a huge crowd largely by virtue of the fact that they had a double bass. The instrument sounded fine, but it was how it looked that was most impressive. Even when you couldn’t hear it, the sight of the bassist spinning his instrument around and merrily running up the side of it was eye-catching enough to make the crowd part with their loose change. Moreover, it was clear that the strings on the bass were big and thick and bruising – hardly the kind of thing that I could break. So, one Saturday morning, Matt and I purchased a knackered plywood bass for about £50, which we then took straight out to Manchester’s St Anne’s Square for a road test.

It didn’t seem to matter that I had never played a double bass in my life – people literally started putting money in the hat as soon as we got there, clearly impressed that someone had bothered to lug such an impractically unwieldy instrument out on to the street in the first place. Over the next few years, I would get used to the string of witticisms (“You’ve been over-feeding that violin!”; “Bet you wish you’d taken up the harmonica!”) which people feel positively compelled to utter when faced with someone carrying a bull fiddle. But that same compulsion also seemed to ensure that they wouldn’t walk by without chucking a few coins in your direction.

The first day we busked in Manchester with the double bass, we broke £100. Part of the key to our financial success was having a “bottler” – someone who would walk around the crowd with a hat while the band were playing, ensuring that no pocket went unemptied. Legend has it that the word “bottler” came from a tradition whereby someone would go from table to table in pubs collecting money for the musicians, with a hat in one hand and a bottle in the other. In the bottle was a fly, which the bottler would keep trapped with his thumb. If they took their thumb off the bottle (in order to reach into the hat and steal some of the money), the fly would escape and they would be undone. It’s a fanciful story but one we enjoyed telling when explaining the origin of our band name, the Railtown Bottlers.

Injuries were always a big part of busking. The first day that I played the double bass in Manchester, I split the ends of the fingers on my right hand and proceeded to bleed all over the instrument – something which seemed to impress the crowd mightily. For a while I tried playing while wearing gardening gloves.

By the time we got to Edinburgh the next summer, I had got into the habit of rubbing surgical spirit into my hands and binding my fingers with Micropore surgical tape. None of this impressed the bassist of the rockabilly band whom we had seen busking there the year before, and who turned up one afternoon to watch us play with an air of great disdain. At the end of the set, as I attempted to clean and rebandage my bleeding hands before we started again, he came up to me and said five words which would become a band mantra.

“Kin ye no’ slap it?”

“Um, you mean can I play slap bass?”

“Aye,” he said, his grin turning to derisive laughter. “Slap it, pal. Ye kin slap it, no?”

I felt at once crestfallen and deeply ashamed. For all the blood and bruises, he had seen right through me. The truth was that I could “no” slap it.

According to one popular folk tale, the art of “slapping it” was invented by Bill Johnson of the Original Creole Ragtime Band who broke his bow in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1911 but carried on banging away with just his hand – and really liked the resulting sound. By snapping the strings of the bass against the fingerboard and then smacking the wood with the open hand, you can effectively mimic the sound of a snare and bass drum with the added bonus of a loud bass note. It’s not pretty, but it is effective.

It’s also impossible to do until someone shows you how to do it – and up until this point I hadn’t met anyone with that particular skill set. “Can you show me?” I asked, less in hope than fear. “Kin I show ye?” he replied. Then, grabbing the bass out of my bloody hands, he spun it round towards him and proceeded to slap the hell out of it, producing runs, triplets and mind-bending paradiddles with his right hand with an effortless ease that made me shiver with envy. The sound was astonishing, as if he’d suddenly been joined by a drummer who was even now hiding within the body of the bass. It was like watching a magic trick, and I was utterly mesmerised. “How do you do that?” I asked, genuinely baffled. “S’easy!” he said.

He was lying. It wasn’t easy. In fact, it was very hard and very painful. At one point, while learning to slap, I pulled a flap of skin off the end of my middle finger that was so sizeable I thought I might have to go to hospital. In the end, I reattached it with superglue. Later on, I briefly lost the feeling in my right hand and had to gaffer tape a fork to my palm so that I could eat. Every night, I would bathe my knuckles in surgical spirit and every morning I’d wake up with a headache caused by inhaling those toxic fumes. For years, I had been breaking strings; now the strings were breaking me.

It was horrible. But it was worth it. Gradually my hands hardened up and my slapping technique improved. And once I’d got the technique, nothing could stop me. I felt like I’d been inducted into some super-secret society – given the key to a life-changing knowledge which had been passed down from generation to generation, from master to pupil. The next summer, the Bottlers played a residency at Edinburgh’s Pleasance theatre and the jazz-musician-turned-journo Miles Kington came to review a show. Afterwards, he came up to me and asked me to explain how I made all “those percussive noises” with my bass, and then he wrote a lovely column in the Independent which made me sound like the best slapper in the world – in a good way.

The downside of slapping, of course, is that it takes its toll on the instrument. One evening in the early 1990s, the Bottlers were playing a gig at the Trolley Stop in Hackney, a venue which had become our second home in the south. Towards the end of the gig there was an ominous cracking sound from the place where the neck of the bass meets the body and, a few thumps later, my instrument – named Eileen – exploded. The weighty wooden headstock flew out into the crowd and struck a guy with a particularly splendid quiff squarely in the middle of the forehead. It hit him hard enough to draw blood that was still trickling down his forehead into his eyes when he came to speak to me after the gig. I thought he was going to hit me; instead, he hugged me.

“That was amazing!” he groaned, as his blood seeped on to my shoulder. “I have never seen that happen before! Never!”

I looked at his forehead, which had a nasty headstock-shaped gash.

“You should get that stitched,” I said. “It’s going to leave a scar.”

“I bloody well hope so!” he roared, before embracing me again and heading towards the bar to show off his war wound. For sentimental reasons I kept the broken neck of that bass. I still have it in my office where it sits next to the neck of the Delta guitar I built as a child. Since then, I’ve trashed another two double basses, one of which was actually built out of a wardrobe by a jazz musician in Manchester named Les, who had made it his mission to create an instrument which I could not break. Inevitably, I turned it into firewood. For my 30th birthday, I drove out to Thwaites music store in Watford where I bought a lovely old 1950s ply-job that did grand service before finally giving up the ghost just before I turned 50. At which point, Thwaites set about building me an entirely new instrument, which is my current weapon of choice. (I fully expect it to fall apart by the time I turn 70.)

But for me, skiffle has always been more about attitude than the instruments. Having shambled my way through any number of musical genres, I felt at home with something which celebrated the triumph of amateurish enthusiasm over technical skill. Here at last was a musical form in which my total lack of proficiency was an asset rather than a hindrance – a type of music in which hitting an instrument rather than playing it was seen as a plus.

My wife Linda and I recently celebrated our 26th wedding anniversary. Whenever I ask her (as I often do) what it was that finally persuaded her that I was indeed the man of her dreams, she always shrugs and gives me the same answer: “It was the double bass.”

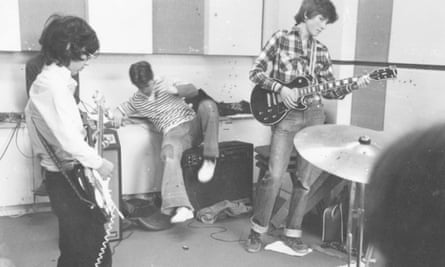

The more I think about it, the happier I am that I turned out to be such a rubbish guitarist. As a kid, I’d never really thought of being a bassist as something to which to aspire. When I saw bands like Slade or the Rubettes on Top of the Pops, my attention was always on the guitarist or the singer, the two people who traditionally vied for the spotlight. In the house where I grew up in Finchley, there was a wardrobe with a mirror on the inside of the door, and when everyone else was out I’d practise rock star poses in front of it. I thought that owning and playing an electric guitar would open the door to my dreams. Later, I’d invested every penny I had in overpriced guitar amps and effects pedals. At school I’d organised entire weeks of music concerts just so I could get the chance to play my Westbury Deluxe in front of an audience. At university in Manchester I’d charged around stages with someone else’s black Stratocaster, convinced that it held the key to eternal happiness.

It sounds pitiful, but the fact is that, for a great portion of my life, I believed that an electric guitar could win me the adulation I so sorely craved. When it finally transpired that I was simply never going to be a heroic axe-wielder, my disappointment was crushing.

And yet, as it turned out, my incompetence was entirely providential. If I’d ever been any good at the guitar, I would never have wound up playing the double bass. The fact that I never rose above the level of cack-handed chord-basher led me to abandon the guitar in favour of an instrument which was tailor-made for someone for whom enthusiasm had always outstripped technique.

And, as it turned out, playing that instrument made the girl of my dreams agree to marry me. For that I will always be the world’s most militant and most grateful bassist.

How does it feel? It feels wonderful.

How Does It Feel? A Life of Musical Misadventures is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (£18.99). To order a copy for £16.44 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Kermode’s new album with the Dodge Brothers, Drive Train, is out on 24 Sept on Weeping Angel and he is touring his show How Does It Feel? (details: markkermode.co.uk)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion