Although staged sword fights date back to Elizabethan theatre and evolved into a key element of swashbuckling action movies from cinema’s early days, fight choreographers have seldom been given their due.

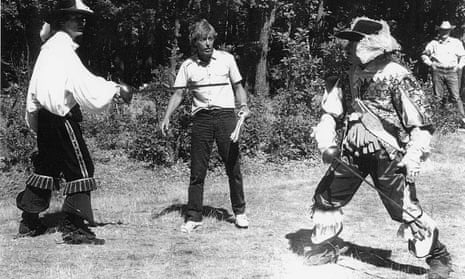

William Hobbs, who has died aged 79, was one of the “sword masters” who devised exciting, gritty and inventively staged duels, notably in Shakespeare productions at the National Theatre at the Old Vic under Laurence Olivier in the 1960s, and in films such as Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971), Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers (1973) and The Four Musketeers (1974), Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977), John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981) and Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s Cyrano de Bergerac (1990).

For his Macbeth, Polanski said: “Hobbs gave me a completely new effect – a thudding blade and body-bashing reality – something that, strangely, had not been done before. I didn’t want anything theatrical.” Therein lay the effectiveness of Hobbs’s approach – he achieved a sense of reality. Film allowed him a greater possibility to evoke the blood and sweat of combat, while theatre could give only the illusion of physical contact to avoid harm to the actors.

Hobbs got closer than most in stage plays. A good example was the climactic duel in a 1995 Broadway production of Hamlet starring Ralph Fiennes. Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times that the sword fight “has an intensity seen more often in a swashbuckler than in a Hamlet”. Hobbs had by then already choreographed about 25 Hamlet duels, he recounted in his book Fight Direction for Stage and Screen (1995), which caused him to ask himself: “What the hell am I going to do this time to make it different?”He was born in Hampstead, north London. When he was very young, his father, Kenneth, a Lancaster bomber pilot, was shot down and killed in a raid over Germany in 1942. In 1948, William’s mother, Joan (nee Kerlindsay), accompanied by her sister, Lesley, took him to live in Australia. Both sisters were in show business: Lesley had her own radio show and Joan was an actor. At school in Sydney, William took up fencing, and soon began winning competitions. At the same time, he became hooked on the theatre.

Returning to the UK, he was soon able to satisfy both his passions. Hobbs studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London for three years. “I was not a very good actor, but I was always very interested in the fight scenes, until then Britain did not have a combat specialist for the stage,” he said. “The only people who were in charge of it were mostly very good sports coaches, who had nothing to do with theatre or cinema.”

He got his first jobs in repertory theatre, before joining the Old Vic, where he stayed for nine years, starting by choreographing the fight scenes in Franco Zeffirelli’s acclaimed production of Romeo and Juliet in 1961. Less than a year later, he worked on his first film, HMS Defiant (1962). “I found it very educative because I had not found anyone to teach me. From the beginning I always tried to think my choreographies through the characters who had to fight.”Hobbs’s career from then on was based around swashbuckling films. The ultimate duel in Rob Roy (1995), between Liam Neeson (in the title role) and Tim Roth as the villain Archibald Cunningham, takes unexpected turns fought in the cellars of a castle.

The climax of The Duellists makes much out of a clash of pistols between Harvey Keitel and Keith Carradine. Hobbs also proved that he could direct such elaborate fights in a comic manner, particularly those involving Michael York as D’Artagnan in the Musketeers films. His final contribution to screen action came in the TV fantasy drama Game of Thrones (2011).

In addition to his film and theatre work, Hobbs brought realism to that most unrealistic of art forms, opera, working with the director Elijah Moshinsky on a number of Verdi operas, including Otello and Aida, at Covent Garden.

He is survived by his wife, Janet (nee Riley), whom he married in 1961, sons, Laurence and Edwin, and two grandchildren, Joanna and Adam.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion