The Problem With Happy Endings

From tidy stories of reunited migrant families to #PlaneBae, Americans’ bias toward optimism is a wonderful thing—until it’s not.

Late last week, as the world’s attention was tugged in the typical directions, a 6-year-old girl named Alison Jimena Valencia Madrid was reunited with her mother, Cindy. The two, who had fled El Salvador earlier in the summer, had been separated more than a month before, at the U.S.–Mexico border, in fulfillment of the Trump administration’s policy of breaking up migrant families as a deterrence to immigration. While the little girl—she goes by Jimena—was in many ways just one of the more than 2,000 children believed to have been incarcerated as part of that project, she was also, in another way, a singular one: Jimena was one of the kids who had been heard wailing, in the audio distributed by ProPublica, for her lost family. Jimena—or, more specifically, her disembodied voice, sobbing and disconsolate—became, in that, one of the symbols of a governmental policy that treats cruelty not as a byproduct of hard choices, but as precisely their point. A wall by another means.

Because of that, you could read the reunion between Cindy Madrid and her daughter as a decidedly bittersweet occasion—an event that occurred only because a federal judge ruled that separated families must be made whole again by the end of this month, if only to be detained as a unit, and one that could very well end with Jimena and her mom sent back to the country they fled. But CNN, whose cameras were on hand to document the Madrids’ meeting, emphasized the sweet over the bitter. “You heard her cry for her mom. See their reunion,” the network promised, selling the segment that follows Jimena in the last, brief leg of her long journey to reunite with Cindy. The network was true to its suggestion: Its segment is on the one hand heartwarming and empathetically reported and perfectly attuned to the cable-news context—and on the other a piece of insistent feel-goodery that highlights the happiness over the many alternatives. It is Time Life and Lifetime, rolled into one.

CNN’s reporter, Gary Tuchman, accompanied Jimena, along with two social workers, on the journey, and he reports on the easiness of the trip: During the flight to Houston, he shares, Jimena played with a doll, colored in a coloring book—as evidence, CNN’s camera zooms in for a close-up shot of Jimena taking crayon to paper—and, in general, took the first plane flight of her life in admirable stride. “Ella no tiene miedo a la avion,” Tuchman informs Cindy, by phone, in stilted Spanish, when the two talk after Jimena’s flight lands: She wasn’t scared on the plane. Jimena, seated next to Tuchman, nods, sipping from a pink water bottle after munching a cookie. Tuchman continues, this time talking to Jimena herself: “Tu es muy fuerte—you are very strong. Right?”

She grins and nods again. He chuckles.

“Good news is rare these days,” Hunter Thompson wrote of a truth that manages to keep being true, “and every glittering ounce of it should be cherished and hoarded and worshipped and fondled like a priceless diamond.” It’s a vintage insight that has only gained relevance in the age of Twitter and memes and jokes like “today was a long week”: The American media may have a reputation for reveling in tragedy—the familiar indictments of disaster porn—but they also have a bias toward the very thing CNN was offering when it shared the story of Jimena Madrid while emphasizing cookies and coloring books: We denizens of the current news cycle are in constant need of happy things. We will look for them even in—especially in—the stories that are, manifestly, tragic.

Often, that search will render as the simple sharing of silly news, fun news, low-stakes news, set against the slow-moving sadnesses of the broader cycle: that amazing video of the bear that took a dip in the backyard hot tub after drinking a margarita; cheeky ratings of people’s dogfriends; memes; gifs; hashtagged puns; assorted fake holidays (happy #nationalhotdogday, by the way, to you and yours). Sometimes it will manifest as explicit promises made by news organizations to their audiences: The New York Times’ The Week in Good News newsletter, the Good News Network, The Huffington Post’s Good News vertical (and the Today show’s, and Fox News’s).

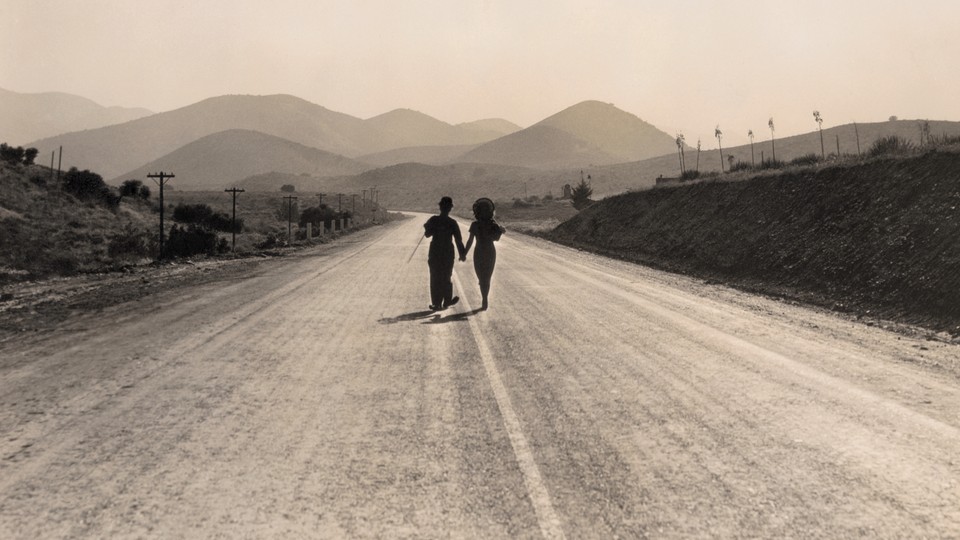

Just as often, though, the impulse—the deep desire for happy endings, which is also to say for stories that give the comforting illusion of closure—will manifest as serious news that has been honed and polished into that most glittering of Thompsonian diamonds: the tragedy overcome. As in, for example, the mother and daughter, desperate for a better life, torn apart—but now, be assured, reunited. The terrible story that is given, via the easy alchemies of the cable-news fast-cut, a satisfying conclusion.

CNN’s segment on the reunion of Jimena Madrid and her family does not share the precise moment of reunion between mother and daughter. Instead, it airs footage of Jimena and Cindy, hand in hand, walks out from the airport corridor and into the airport garage. Jimena looks giddy. Cindy looks tired. The camera shutters flutter at them—chk, chk, chk, chk, chk—dutifully capturing the moment. “¡Sonrisas!”—Smiles!—Tuchman says, cheerily, as the newly reunited family moves into the open air, and it is difficult to tell, in the video, whether the remark is a description or a suggestion.

Either way, the family concedes. Jimena offers a wide grin; Cindy manages a weary one. They will repeat the expressions—chk, chk, chk, chk, chk—during a press conference, conducted after the reunion before a large banner that reads bienvenida allison (there is discrepancy, among the American media, about the girl’s name). During the press event, in the small section of it that CNN airs, Jimena will reaffirm how happy she is to be with her mom again. “Mother and daughter will live with Cindy’s sister in the Houston area while proceeding with her asylum claim,” Tuchman’s voiceover ends the segment, “hoping the sadness and separation are behind them.”

The reporter, in this, might also be describing the feelings of the viewer. In a time of hard news, in every sense, the stories of family separations have been, after all, particularly challenging: kids in cages. A baby torn away by government agents from her mother’s breast. A father who killed himself when faced with the possibility that he would never see his family again. The wailing of small children. And so: When CNN tells its audience that one of those sobbing children has been reunited with her mother, it is not just providing a happy ending; it is also offering reassurance to a flagging public that the story overall is, indeed, coming to its conclusion. It is offering tacit permission to look away, to stop paying attention, to stop investing and feeling and caring. The arc has ended, after all; the reunion has happened; they are hoping the sadness and separation are behind them.

But the Madrid family’s story, of course, has definitely not ended. Not only for the obvious reason—Cindy will now be engaged in a challenging legal battle for asylum in a nation whose news has been saturated with dire, if straw-manned, warnings of the perils of “open borders”—but also for the reason that tends to go unacknowledged in the easy symmetries of the family reunion: Trauma has a way of waiting and whispering and weaving itself into human hearts. The coloring books, the cookies, the bright grins—these are temporary assurances. How much will Jimena share, in the end—in the real end of the story—with her fellow 6-year-old Jefferson Che Pop, who was reunited with his father, Hermelindo, after nearly two months of separation sporting a bruise, a rash, a cough, and a total inability to recognize his dad? How much will she be affected by the series of rules that forbade incarcerated children from touching one another, even to give hugs? Did the stress of it all ever cause Jimena to misbehave? Was she ever given injections that would keep her quiet?

There are so many other stories haunting the main one. They are hinted at in another treatment of the Madrid family reunion—this one captured by ProPublica, the publisher of the original audio of Jimena’s wails. The outlet’s comparatively rough footage of the mother-daughter reunion in Houston, a version of the story that has not been spliced into CNN-size sections, presents a perspective that is decidedly different from the one the cable network aired: Its prevailing tone is ambivalence, especially on the part of the mother who has been separated from her daughter for weeks on end. In it, Cindy seems to be trying to smile, but failing. She seems to be trying to perform cheer, but not quite able to. CNN’s segment features Jimena, cheerfully shouting “¡Hasta luego!”—Bye!—seemingly unprompted as she gets into the van; ProPublica’s video shows that she is simply repeating Tuchman’s own farewell to her. The uncut footage of the Madrid family reunion emphasizes the uncomfortable thinness of the line between the happy ending that is lived and the happy ending that is bestowed.

The week that found Jimena Madrid reunited with her mother, a very different kind of story was lingering, still, in the exhaust fumes of faded virality. #PlaneBae, as that story came to be known, began when the actor and comedian Rosey Blair live-’grammed an encounter between two strangers who met on an airplane—their faces obscured, but their interactions otherwise documented in wincingly precise detail. As Blair narrated their story, my colleague Taylor Lorenz pointed out, she applied a well-worn script—that of the serendipitous romance, of the insistent dreams of the rom-com—to facts that may or may not have warranted it. Blair assumed romance. Blair assumed love. Which is also to say: Blair, in telling a story that was not hers to tell, started with the happy ending, and then stretched the soft truths of the matter to conform to its mandates.

As it wore on, the story of #PlaneBae shed whatever small dignities it might have started with. The fact that Blair had originally obscured the planebaes’ faces was nullified when the guy in the saga, Euan Holden—who turned out to be (formerly) a professional soccer player and (currently) a model—outed himself through eager appearances on morning shows and other media. Things got worse still when Blair capitalized on all the attention by asking for a job at BuzzFeed, and also a job in Hollywood, and also money. And they reached their nadir when Holden’s alleged new love interest, who repeatedly affirmed her desire for privacy, was doxxed—and then promptly subjected to the abuses that tend to befall those who have the audacity to be both women and online.

The #PlaneBae saga, as it played out, proved itself to be what it had been the whole time: exploitative. Creepy. A happy ending in search of a story. Soon, Blair was apologizing to the woman whose life she had co-opted. And that woman, for her part, was issuing a statement through her lawyer: “#PlaneBae is not a romance—it is a digital-age cautionary tale about privacy, identity, ethics, and consent.”

So are, in many ways, the tales that have been emerging as migrant children have been, slowly, reunited with their families at the U.S. border. CNN’s cheerful segment on Jimena Madrid’s reunion with her mother is by no means a #PlaneBae-style exploitation. (“God put an angel in her path to record that audio,” Cindy Madrid told CNN last month, emphasizing her willingness to be publicized.) Both treatments suggest, though, how easily the desire for a happy ending can insinuate itself on the facts of the matter. The possibility at play in CNN’s take—and in the many similar ones that have been offered up by other news outlets—is that the full story, and its attendant horrors, will get washed away in the easy rituals of false closure. It is that people will forget, because the logic of the happy ending has given them permission to be preoccupied. The Madrids’ reunion is from one perspective, of course, the best news—they’re okay, despite it all!—but it is from another, of course, incomplete news. Will they be okay, despite it all?

In 2009, Barbara Ehrenreich published her book Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America. In it, the journalist detailed how biased Americans are toward optimism—in the best ways as well as the worst. She documented how unwilling and unable we can be, as a culture, to grapple with things that are difficult and scary and manifestly sad. She documented our great ability to look away. “We need to brace ourselves for a struggle against terrifying obstacles,” Ehrenreich wrote, in summary, “both of our own making and imposed by the natural world. And the first step is to recover from the mass delusion that is positive thinking.”

I thought about Ehrenreich as I watched CNN share the good news of the Madrids’ reunion. I thought about her as the cameras whirred and a U.S. border agent cleared the family for temporary release and the reporter telling their story shouted a merry “¡Hasta luego!” in their direction. I thought about Ehrenreich as I watched Jimena Madrid and her mother, relieved and weary, driving away to prepare for a fight that has only just begun.