Orla Kiely’s name is almost as well known now as her rounded-leaf pattern Stem, a design so popular it functions like a trademark. As a result of such commercial success, many of the visitors to the exhibition of Kiely’s work, Orla Kiely: A Life in Pattern, which opened at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London on 25 May, will already be well aware that they own either a tea towel, a patterned kettle or a cushion emblazoned with one of her upbeat, retro-inspired prints.

But what of the legacy of the equally influential women textile designers who went before Kiely: women such as Enid Marx, also once hailed as Britain’s “queen of patterns”? Commuters on British buses and London tube trains may no longer recognise her name but for decades they have been paying a fitting tribute to Marx’s practical designs by simply sitting on them. The artist’s familiar woven geometric fabrics, and later designs inspired by her work, have done much to brand the transport system since the day in 1937 that she was first asked to sketch them.

Art historian Dr Alan Powers says: “We all respond to pattern, and we could really do with more of it around, but Enid Marx did it better than anyone I have come across.”

An exhibition about Marx, the first dedicated to her work for 40 years, also opened in Londonon 25 May. “She sets a standard much higher than most,” Powers adds. As well as co-curating the show Enid Marx: Print, Pattern and Popular Art, running at London’s House of Illustration, Powers is author of a new book, Enid Marx: The Pleasures of Pattern, about Marx’s distinctive talent and unorthodox career.

She is, he believes, one of a succession of great women designers and illustrators who still shape the world we look at and who are finally being given their due recognition as cultural figures. They survived in an era when female printmakers were rarely trusted with the bank loans or investments that might have allowed them to set up their own design houses. Instead they worked anonymously as freelancers.

The Irish designer Kiely and her British contemporary Cath Kidston, a print superstar whose empire is built on traditional English patterns, may seem like phenomena of the modern age. Yet talented artists such as Marx, or her forerunner Minnie McLeish, whose vibrant textiles were popular in the 1920s, were really there first, and their ideas continue to colour and mould the products and fabrics around us.

Marx, known to her friends as Marco, was born in 1902 and was a distant relative of Karl Marx. As a pupil at the prestigious Roedean School for girls, in Sussex, she trained in carpentry, later expressing a wish that all schoolgirls could be given such a chance to experiment with wood. At art school in London, the young Marx began making the bold block print designs that quickly defined her as part of the interwar creative movement led by her better-known male peers, the artists and designers Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden.

According to Powers, Marx would often modestly protest that her most enduring design ideas “were just in the air at the time”. Nevertheless, Olivia Ahmad, Powers’s co-curator on the House of Illustration show, sees Marx as “a pioneer” and a woman “whose broad interests in abstract modernism and popular art traditions inspired remarkable achievements in textile design, book illustration and printmaking”.She adds: “Her distinctive contribution to this critical period of British design deserves the same recognition as Bawden or Ravilious.”

The opportunity to brand their own products made a big difference to women designers in more recent times. Once Laura Ashley had started to sell her floral designs in her first outlet in 1961, her name quickly became a byword for a romantic, rural style of dress. “Laura Ashley had shops, of course, and that is really why we have still heard of her,” says Powers.

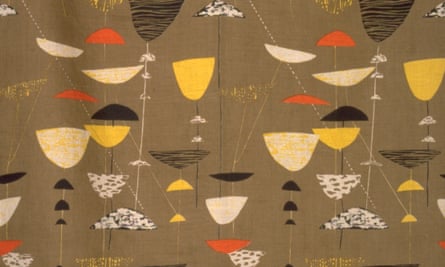

A decade earlier, in the middle of the white heat of technology, came Lucienne Day, who was perhaps the most copied fabric designer of the mid-20th century, although not a household name today. Her forward-looking fabric patterns, including Dandelion Clocks and Calyx, created for the 1951 Festival of Britain, have become classics and are still selling at John Lewis.

Admirers of her work have been making pilgrimages to a touring exhibition, Lucienne Day: Living Design, devoted to her archive. This show, created by Arts University Bournemouth last year, finished a long run in Cirencester, Gloucestershire in May and will go on later this year to Dublin Castle and then to Banbridge, County Down, Northern Ireland.

“Lucienne Day was more famous in her own time than Marx ever managed,” says Powers. However, he adds: “It is true that her name is not so well remembered now, because she went out of fashion for two or three decades.”

The reputation of Day’s husband, the designer Robin Day, has been better preserved, largely due to the quintessential modernist stacking chair that bears his name.

Marx cut a less fashionable figure than Day or Ashley, but had a similar impact on the environment around her, says Powers, who knew her in the last years of her life. “I contacted her because I wanted to print one of her papers. She was small, ebullient and intense, and very interested in traditional English art. Writing about her, I found she had gained international attention for her prints when she was still quite young, but had done little work with furnishing textiles when she was asked to design for the tube.”

Creating the thick fabric, or moquette, for the trains’ seating, she eventually settled on strong colours that would wear well: dark red to represent the city, dark green for the countryside. “The first fabrics were for the Northern line, which runs out of the city and above ground, so they had to look good in artificial light and daylight,” says Powers.

While studying under the painter Paul Nash at the Royal College of Art, alongside Ravilious and Bawden, Marx was commissioned to make book cover prints for Curwen Press using wood block engravings. In the 1930s she designed covers for Chatto & Windus, and later worked for Faber, submitting designs as a freelancer from her north London home. During the second world war Marx worked on Utility fabrics, frugally made prints aimed at cheering up the population. She designed for the utility furniture scheme from 1944, creating 30 upholstery and curtain fabric designs with the limited supplies of available yarn.

Marx’s posters for London Zoo are on show in the House of Illustration exhibition, as is other work revealing her love of drawing animals and insects, particularly Siamese cats. In the months ahead of her death in 1998, she began to worry that her archive and collection of artefacts would not be seen by the art students and designers of the future.

“She was very concerned that her store of work should be seen, so that it carried on influencing people,” says Powers. “It is quite a nice end to her story that in her 90s she was not forgotten. She was approached by Compton Verney, the gallery in Warwickshire, who took on much of her archive. So happily, her wish is still coming true.”

Enid Marx, Print, Pattern and Popular Art is on at the House of Illustration in London’s Kings Cross to 23 September

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion