There’s an African proverb that goes like this: until the lions have their say, the hunters will always tell the story. It is the victors who write history. But as the west has mostly written history, some stories have gone untold: like the millions of colonial soldiers who fought for Britain in the first world war.

Xenos is the story of an Indian colonial soldier. It started off with the idea of Prometheus, who created mankind out of clay and mud.

Prometheus had the foresight to know that humans are doomed to destroy themselves – and yet he still had hope in them. He stole fire to better humankind. I wanted to make the Promethean myth relevant to a war that our great-grandparents lived. So the myth was absorbed within the narrative of a soldier.

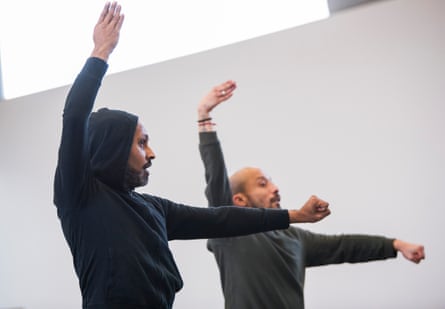

In my work, I need a character I can relate to – but also a character who can relate to me. So we decided that this colonial soldier was a dancer who is thrown into the trenches somewhere in Europe. Most of the piece takes place in a trench, at least in an abstract sense.

I worked with my dramaturg, Ruth Little, and a writer, Jordan Tannahill. Jordan said the more text you can get rid of the better. In Asian culture, our meanings are in our actions not our words. British theatre is predominantly text-driven, though it’s changing a lot now.

Ruth, Jordan and I agreed that the action of the story had to be told by the body not by the words.

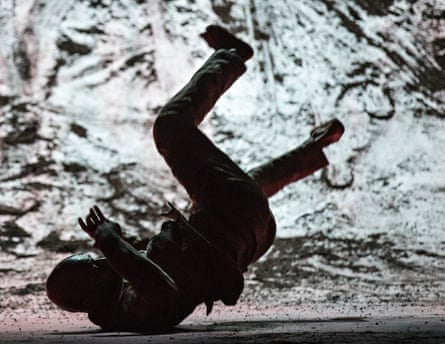

The designer Mirella Weingarten was amazing to work with. She created hell for me and she was absolutely happy to do that. She said: “You need to struggle with the elements.” I said, I’m struggling with the biggest element: my age! I’m fighting time.

On Xenos, I’m working again with Michael Hulls. He is the god of lighting for dance. He created a unique aesthetic for dance.

When I discuss the work with Michael, I talk more about the lights and he talks more about the dance. In the end, I’d say he uses 1% of what I talk about in lighting and I use 1% of what he talks about in dance.

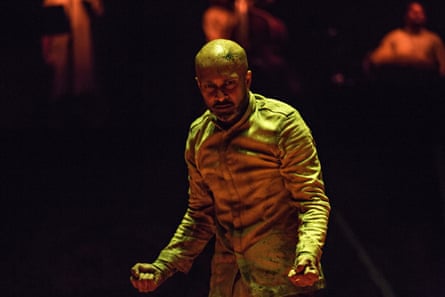

Xenos is my last full-length solo. I wanted to go back to classical dance, which is where I started. Indian musicians sing while the audience comes in, and the opening scene is a mini classical concert.

Each piece I create is a three-year process. The first year is really about having an idea and inviting collaborators. The second year is about meeting up regularly, talking about the subject and collecting a lot of images, poetry, text and historical facts.

The third year is all about the movement. We spend two to four months in the studio and a few weeks in a theatre. This time, we spent six weeks on stage – first at the Grange in Hampshire and then in Athens.

We premiered Xenos in Athens in February. The show continues to change, but this transformation now happens on the stage rather than in the studio.

Before going on stage I usually spend two and a half hours in my dressing room. I meditate, which for me is sleeping, basically. It’s to silence my head and still my body. Then I warm up in a specific way, which is meditation. Ten minutes before the show starts, I go through a ritual of thinking: what can I say to cancel the performance? I am terrified. But once I’m on stage I’m fine. It’s about getting from the dressing room to the stage – I have a whole Greek drama going on in my head during that walk.

By the end of Xenos, clay is all over my body and earth lies across the stage. This last scene is about rebirth. This capitalist way of living is going to finish. This way of extracting from the Earth and not giving back? It will be the end of us. As a civilisation, as a species, we have to live in a new way.

Xenos, commissioned by 14-18 NOW, is at Sadler’s Wells, London, from 29 May to 9 June. Then at Edinburgh international festival, 16–18 August.

- Interview by Chris Wiegand. Rehearsal shots by Tristram Kenton for the Guardian. Production shots by Jean Louis Fernandez.