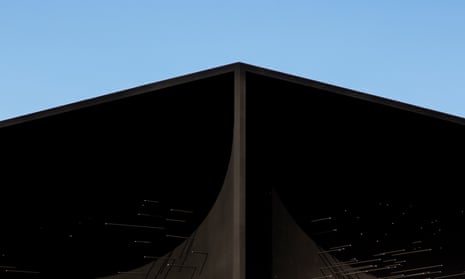

The pistes of Pyeongchang may be blinding white with snow as the Winter Olympics kicks off in South Korea, but among the ice rinks and bobsleigh tracks stands something completely different: the darkest building on the planet. Lurking between the competition venues like an angular black hole, it looks like a portal to a parallel universe, waiting to suck unsuspecting ski fans into its vortex. But this is not the latest high-tech defence against North Korean attack. It’s a temporary pavilion for car giant Hyundai, designed by British architect Asif Khan, using a material developed in Surrey.

Described as the world’s largest continuous “nanostructure”, the building has been sprayed with a coating of Vantablack Vbx2, a super-black material that absorbs 99% of the light that hits its surface, creating the illusion of a void.

“It’s like a nano-scale coral reef,” says Ben Jensen, chief technical officer of Surrey Nanosystems, which has developed the material. “Photons get into it and they bounce around within its structure until they’re all absorbed. The optical cavities in the ‘reef’ are around 1,000th the width of a human hair.”

The material was developed for architectural application after the interest stirred up by the launch of the company’s original Vantablack S-VIS in 2014, which it controversially licensed exclusively to the sculptor Anish Kapoor. Made of vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays – hence the name Vanta – the substance was invented for space and defence use, to reduce atmospheric distortion in telescopes and cut out stray light refraction from polished lenses. But Kapoor saw its potential for his perception-bending sculptures, describing it as “the blackest material in the universe … it’s literally as if you could disappear into it”.

His exclusive deal to use the material raised eyebrows in the art world and prompted artist Stuart Semple to develop the “pinkest pink” and “glitteriest glitter”, available for anyone to buy on the internet, with the specific exception of Kapoor. “It just seemed really mean-spirited,” said Semple, “and against the spirit of generosity that most artists who make and share their work are driven by.” Kapoor responded by posting a photo on Instagram of his middle finger, dipped in the fluorescent pigment.

“The level of interest really took us aback,” says Jensen. “We were inundated by architects and designers asking how they could use Vantablack, with ideas for everything from museum interiors to hiding unsightly cabling runs in the ceiling.”

Khan beat a path to the Surrey laboratory in 2013. The 38-year-old designer has built an international reputation for experimenting with innovative materials and technologies. He designed the world’s first “selfie building” for the Sochi Olympics in 2014, with a facade that morphed into the contours of visitors’ faces, followed by a pavilion inspired by graphene for the Astana Expo in Kazakhstan last year.

“Architecture is always 50 years behind technology,” he says. “Things developed for cars or aerospace eventually make their way into buildings, like modern cladding systems, which essentially come from car manufacturing.” Just as Mies van der Rohe used large panes of sheet glass in his seminal Barcelona Pavilion in the 1920s, or Erich Mendelsohn used arc welding in the De La Warr pavilion in Bexhill in the 1930s, Khan hopes that his demonstration of this new nanomaterial might open up a new avenue of innovation for architects.

“It’s just the beginning of a brave new world of microstructures, whether it’s the technology used to filter sea water or materials developed for superconductivity. We’ve been looking at the possibilities of ‘structural colour’, too, which is the ability for materials to have colour properties within their physical structure, like butterfly wings.”

Khan’s Pyeongchang pavilion features thousands of pinpricks of light on the end of rods, modelled on the position of stars as viewed from that point on the earth, set at different depths, creating an illusion of floating in space as you walk around the building. Inside, the mesmerising blackness gives way to a bright white interior, where water droplets dart around in little channels milled into white acrylic tables, inspired by Hyundai’s launch of a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle.

Surrey Nanosystems is due to launch Vantablack Vbx2 next month, but before you rush to B&Q or start planning how to turn your bedroom into the blackest boudoir on the planet, it won’t be for sale in the shops. “It’s never going to be a retail product,” says Jensen. “It has to be applied by specialist contractors trained by us, using a technique that forms a consistent nanostructure. It doesn’t come in a spray can.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion