The words “industrial luxury” are emblazoned on a window as you approach the cluster of majestic iron gasholders standing on the edge of the canal in King’s Cross. Built in the 1860s near St Pancras station, and dismantled in the 1990s when the station was expanded, the cast iron frames have now been reborn as the skeletal enclosures for three cylinders of luxury apartments – with prices beginning at £810,000 for a studio flat and rising, like the former gas tanks, into the many millions for a penthouse.

Industry and luxury are the two magic ingredients that have driven the £3bn redevelopment of King’s Cross in north London, tapping into the collective nostalgia for big brick sheds and the lure of a bit of bronze trim. Across 27 hectares of former railway lands, developer Argent has been piecing together a masterplan since 2000, employing 35 different architects to transform a gritty world of rails and warehouses into a polished vision of postindustrial regeneration. It is one of the biggest such projects in Europe and, despite the crass marketing slogans, it’s shaping up to be one of the best planned.

At its centre stands the 1851 Granary Building, where goods were once hauled between rail, canal barge and horse-drawn vehicles. It’s now a place where students haul themselves between studios, workshops and lecture theatres in the bustling art factory of Central Saint Martins college. Here the urge for luxury may have trumped the functions of industry, creating a place that feels a bit too precious for the messy activities it should serve.

To the south, office blocks have been given a refreshingly raw, brawny treatment. Eric Parry has designed a chunky Cor-Ten steel-clad building, whose big riveted steel plates make an emphatic nod to the site’s industrial past, while David Chipperfield has weighty cast iron columns rising the full height of his facade, lending permanence to the fleeting cycle of speculative office space.

There’s a touch of bling, courtesy of Allies and Morrison’s golden window reveals and dRMM’s silvery apartment block, ArtHouse, which shimmers in the sun like an Airstream caravan. Duggan Morris, meanwhile, brings youthful swagger to the party, dressing its building in jaunty shades of millennial pink. There’s plenty of background brick too, in keeping with the favoured New London Vernacular, most finely crafted in Maccreanor Lavington’s housing block, whose handsome glazed brick facade has an air of turn-of-the-century Chicago.

It’s a broad church, representing the various flavours of contemporary British architecture, and even the classicists get a look in: Demetri Porphyrios has built a slab of dictator chic on a budget, with a building that could be lifted straight from Ceausescu’s Bucharest. Those desiring more jazzy sculptural gymnastics can delight in Thomas Heatherwick’s conjoined rooftops that writhe above a pair of old coal sheds, soon to reopen as a boutique shopping arcade.

More stardust is on the way in the form of his £1bn coppery groundscraper for Google, designed with Bjarke Ingels, its huge size apparently inspired by the “massive railway stations, roads, canals and other infrastructure” of the site. There are some howlers too. Perhaps Glenn Howells was inspired by the area’s former reputation as a bit of a dump: his 27-storey tower of student flats looms at the back of the site like a discarded fridge.

The overall effect has been criticised by the more flamboyant of British architecture’s ageing radicals as being a bit dreary. The late Zaha Hadid called it boring, while her former tutor Peter Cook, the 81-year-old co-founder of Archigram and champion of blobitecture, slammed the project as “unbelievable, really dour”, with buildings that resemble “old biscuits”.

For sure, it is more dry digestive than gelatinous trifle, but that is generally to be welcomed. It is also refreshing to find a development where as much, if not more, attention has been paid to the streets and spaces as the buildings that frame them. It may be the usual kind of overly managed pseudo-public space, but accusations of privatisation are unfounded, given that most of the site was off-limits to the public before.

Less laudable is the developer’s reduction in the quantity of affordable housing. The original agreement signed with Camden council in 2006 specified that Argent would built 750 affordable homes, 500 of which would be available for social rent. But a “cascade” mechanism was built into the agreement to safeguard the developer’s profits, meaning that if minimum prices could no longer be achieved, the quantity of affordable housing could be reduced. In 2015 Argent returned to the council, pleading poverty, and successfully negotiated the number of affordable homes down to 637.

Unsurprisingly, none are to be found in Gasholders, which represent the uppermost tier of Argent’s luxury offer, by far the most expensive project to build so far. After two years of painstaking restoration in North Yorkshire, the 123 iron columns of the grade II-listed “siamese triplet” structures have been resurrected, inside which the new apartments have been built without touching the precious frames at a single point.

This impressive limbo dance is the work of Wilkinson Eyre, specialists in reviving industrial hulks, having transformed an old steelworks in Rotherham into the Magna visitor centre and currently working on Battersea Power Station, and they have brought a similar sensibility to the canalside site. The apartment blocks are set at three different heights, echoing the dynamic movement of the gas tanks, and clad in a continuous skin of perforated metal shutters, giving them the look of supersized washing machine drums. Painted battleship grey, the shutters lend the whole thing a dark, glowering air, and it is an odd choice in the overcast context of London, where blocking out the sun isn’t a particularly common need. Wouldn’t curtains do?

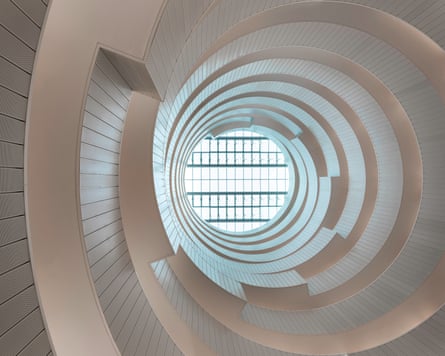

Nor does each cylinder lend itself particularly happily to the creation of useful apartments. Shaped like slices of pie, the pricey flats fan out from the entrance to the windows, where the impressive views are somewhat hampered by the multiple layers of structure, from the gasholder frames to the retractable mechanical shutters. Like many ultra-prime projects of its kind, the finishes feel more hotel-like than homely, an atmosphere furthered by the onsite spa complex and private cinema for residents. Still, the circular geometry provides an excuse for some momentous atria inside, with stacked halos of white balustrades recalling the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and an open courtyard at the centre, where the three frames collide in a spectacular cat’s cradle of struts and braces.

Looking at the smaller, fourth gasholder next door, which has been converted into an attractive park by Bell Phillips architects, you can’t help wondering if stuffing 145 luxury flats inside the other three, with great difficulty and at vast expense, wasn’t the best thing to do – particularly given the glut of high-end units lying empty in London. Didn’t they contemplate other uses, like deep-plan workspace or an atmospheric cultural venue?

“Yes, every week,” laughs architect Chris Wilkinson, whose team was charged with the daily headache of making the plans fit. But his client was harder-nosed. “The project had to be viable,” says Robert Evans, Argent’s partner in charge. “Historic England needed certainty about the future of the frames, and we liked the idea of people living here, somewhere out of the ordinary.”

Leaving the building, I notice some cog-like details inlaid in the floor of the lobby. “They couldn’t sell the industrial aesthetic on its own,” says Wilkinson, “so we came up with the watchmaker reference. When you see the plan of the building, it looks like a watch mechanism.”

Sometimes industrial luxury alone just isn’t enough.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion