Reading at school was agony. A slow, child by child rotation around the class, six pages each. Great Expectations. Vanity Fair. The Mill on the bloody Floss. The boys with their flatline monotones. The girls, careful not to stumble and be humiliated. English was my best subject, so this process was painful. I wanted to race ahead and get to the end of the story. Yet the idea of taking that book home to read later and finish, that never occurred to me. Not when we owned the ultimate big novel: the Bible. We were Jehovah’s Witnesses and three times a week we’d sit in a draughty hall on the backstreets of Sparkbrook in Birmingham, wrapped around a paraffin heater discussing the 66 books that made up the Old and the New Testaments. I’ve read it cover to cover at least five times.

Leviticus and Numbers were hard going, all that counting and recounting, all those laws and exhortations, but there were very beautiful passages, too. The Song of Solomon, Psalms, Proverbs. The Gospels, too, four different takes on one big adventure. They had the ingredients of a good thriller with a hero, a call to arms, a savage tragedy. Without realising it, I was learning what you had to do to write well, how to characterise, how to keep your reader turning the page without the threat of eternal damnation as an incentive.

But writing as a career? That never entered my head. The only writers I knew were dead. And apart from Enid Blyton, they were dead men. And white. And posh. Even when I began to read widely in my 20s, it was still a case of: if you can’t see it, you can’t be it. No one from my background – poor, black and Irish – wrote books. It just wasn’t an option.

I left school at 16, in 1976. Since then we’ve had a range of social mobility initiatives, the policies by which bright children are better enabled to “reach the top”. I’ve always had a problem with the idea of cherry-picking the most able or the most driven rather than lifting whole communities out of poverty, providing better standards of education and better living conditions for all. Worse than that, the notion of social mobility has always smacked of: “How can we help you to be more like us?” It seems to say that to be working class is to be a failure.

Nevertheless, I still wonder if any of these initiatives have made an impression on who gets to write, what they’re allowed to write, who gets published, and by whom. What’s life like, even today, if you’re a writer from the other side of the tracks?

¶

None of the big publishers were interested in Paul McVeigh’s 2015 novel The Good Son, about a working- class Catholic boy in Belfast during the Troubles. “The regional and working-class vernacular put them off,” he says. “I knew if I toned down the voice and made the book less honest and less representative of the lives of children growing up in poverty, it would have had a much easier and financially rewarding journey to publication.” McVeigh eventually found an independent publisher, Salt, willing to take his writing on, but it took months of hard work, and it didn’t stop there.

Karl Parkinson, whose 2016 novel The Blocks is written in the dialect of the poorest part of Dublin, also struggled to find a publisher. And when he did get published, by small independent press New Binary, he “would find that the book hadn’t been stocked in the bookshops”. Parkinson, brought up in social housing rife with unemployment and heroin abuse, says: “I knew that big publishers would ask me to change the uncompromising use of dialect, phonetic spelling, idiosyncratic punctuation. But that’s what made it real.”

A 2016 paper, published by Dr Dave O’Brien of Goldsmiths estimated that almost half – 47% – of all authors, writers and translators hail from professional, middle-class backgrounds, compared with just 10% of those with parents in routine or manual labour. This analysis, of the 2014 British Labour Force Survey, also identified that 43% of people working in publishing, including those in the influential editorial roles, were from middle-class origins, with only 12% from working-class backgrounds. As Chris McCrudden, a communications planner who dissects data on publishing trends, says: “Publishing is an upper-middle class industry whose output caters to upper-middle class tastes.”

This all matters to writers. Why? Because these statistics show publishing to be the least socially diverse of all the UK’s creative industries, including film, television and advertising. If the majority of decision makers – gatekeepers – come from such a narrow social and cultural set (white, middle-class, good contacts, right accent and cultural references), then the question of who gets published and which stories get told is unlikely to change.

¶

When I began writing in my mid-40s, I had little expectation of being published. I knew no writers and little of the publishing world. I wrote as an antidote to being at home with young children. Heavily influenced by my fathers’ fascination with film noir, I had a stab at a screenplay, then a gangster novel, then something about a Norwegian madman. I was feeling my way but not finding my voice, nor did I really have an idea of what I wanted to say, despite having read hundreds of books by then. I only knew that I somehow wanted to tell the truth, to write something authentic, though authentically what I wasn’t sure.

I began reading at 23, while working in a criminal defence legal firm in Handsworth, Birmingham. I asked one of the solicitors if he could recommend 10 good books. He was a military man and the list reflected his tastes: The Riddle of the Sands, The Siege of Krishnapur, The Red Badge of Courage. But he threw in a couple of wild cards: Flaubert and Zola. I followed up Emma Bovary with Thérèse Raquin, The Woman of the Pharisees, Anna of the Five Towns and Helen with a High Hand and began to find a seam of life that I could relate to: the domestic drama; the small world with the big stakes; the people at the edge of things, adrift somehow, out of sorts.

I grew up in the Irish community of Birmingham and the Irish are nothing if not great storytellers. My grandmother from Wexford, a waspish woman with a vinegar tongue, had a mean repertoire of takedowns, and an uncle of mine could spin one throwaway line into a joke, a yarn, a whole evening of entertainment. So when I began writing I wanted to imitate my heroes, to take ordinary, everyday people and make them the centre of the story, as James Joyce does in Dubliners, or as Kevin Barry and Lisa McInerney do with their spot-on, lyrical descriptions of small city lives today.

But there weren’t as many examples to draw from out there as I would have liked. Before the Chartists, in the early 19th century, the working-class voice was repressed by poverty, factory systems, child labour, slum housing and a lack of education. The six-point charter drawn up by the London Working Men’s Association, demanding changes to rights and access to the vote, may have been rejected, but the roots of working-class writing began there. Though Thomas Cooper’s full-length novel about Chartism was lost, early working-class fictions were usually subversions of bildungsroman – the hero not always overcoming poverty, but certainly tackling it head-on and more often with his fists.

Then, in the 20th century, DH Lawrence gave us Sons and Lovers, a tale of sexual irregularity, foundering intellect and desire for class solidarity, told through Paul Morel – bound for the mines and not the middle-class bohemia he strives for. “I belong to the common people,” says Morel. “From the middle-classes one gets ideas, from the common people – life itself.”

The late 1950s and 60s saw something of a heyday for working‑class fiction. Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning presented us with Arthur Seaton, the original angry young man, tethered to the factory line, cheating with his shop steward’s wife, and finally giving in to the idea of a nice little house on a respectable estate. Still, Arthur won’t be told, and like Sillitoe’s previous everyman, Smith, in “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner”, these underdogs are tenaciously sticking it to the man by losing the race on purpose.

But in A Kestrel for a Knave, published 50 years ago last month, Barry Hines showed exactly how humiliating it was to be a loser. A bleak coming-of-age tale, the book recounts a day in the life of an ostracised lower-class boy. Humiliated because of his poverty by his teachers, Billy Casper reeks of hopelessness, and finds solace in taming a young kestrel. He fears that life down a mine will turn him into his bitter, bullying brother, who ultimately kills Billy’s kestrel in revenge for his failure to put a bet on the horses.

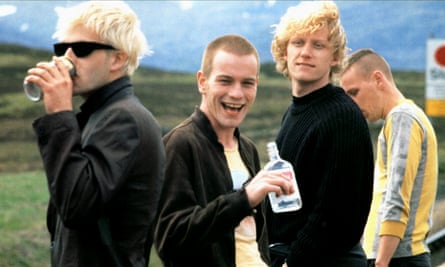

As Thatcherism closed the mines, and crushed the unions in the 1980s, a wave of new Scottish writers dealt with the fallout of unemployment and urban decay. Novels by James Kelman, Agnes Owens, Irvine Welsh and Alan Warner captured the alienation of the angry working man and woman and the rise of an urban underclass brought about by mass unemployment and the fracturing of communities that had previously stood shoulder to shoulder. Traditional working-class values of community, loyalty, family-centricity and pride, gave way in these stories to drugs, gangs and prostitution. But Welsh’s Trainspotting is no mouthpiece for junkie culture; it is clever, witty, raw, class-conscious and angry.

The post-industrial decay of mining towns in Wales is explored today by Welsh writers such as Rachel Trezise, Thomas Morris and Cynan Jones. In The Dig, Jones’s intense novel about a farmer and an illegal badger baiter, the author does just that: he digs in the dirt of the blunt-speaking rural working-class and reveals what you can make from the land to survive. “They had both grown up on farms and knew what to expect,” he writes, “but often it was the modernisation that wearied them.”

Similarly, in Morris’s debut short story collection, We Don’t Know What We’re Doing, the people of Caerphilly are desperately seeking employment. “Whenever a shop closes down, a poster advertising one always appears.” But what never appears is the security and self-improvement that paid work brings. Instead, Morris’s characters are defined by a rose-tinted history.

¶

These books represent, however, only a partial account of the depth and variety of the working-class experience, and one that is often tailored for a middle-class, metropolitan reader. As soon as I thought about getting published, I realised that everyone who seemed to matter was a couple of hours down the motorway. I bought the Writers and Artists Yearbook to look for agents: London. I spotted a reading by one of my favourite authors: London again. The importance of London to becoming a writer or working in publishing is well known. Recent research from the London School of Economics demonstrates that the clustering of creative businesses in the capital reinforces the inequalities in the cultural workforce, and therefore the gaps in what is represented within literary culture.

There are developments happening outside the M25: the Northern Fiction Alliance, a coming together of several independent publishers headed up by Manchester-based Comma Press, has challenged the dominance of the major London houses. But none of the “big five” – Penguin Random House, Macmillan, Hachette, HarperCollins and Simon & Schuster – has yet opened an office outside the capital.

The publishing industry is, gradually, waking up to the need to find new writers and new voices. But the danger in calling for more working-class stories, without a fundamental change in both the workforce and the audience, is that these will end up being just another product for middle-class consumption. In his book, Race and the Cultural Industries, Dr Anamik Saha, a lecturer at Goldsmiths, demonstrates how British Asian authors are restricted to a narrow gap in the market; they are offered the opportunity to write a specific set of racially framed narratives, which publishers claim are the only ones they can sell, rather than being given true creative freedom.

Similarly, working-class writers, it seems, must endlessly regurgitate their own life stories – or versions of them – whereas middle-class writers can explore the world, the universe and beyond. The assumption being that working-class writers and stories are marginal. They are not: more than a third of the population is from traditional working-class origins. And it is also assumed that in order for these stories to be commercial they have to be filtered through middle-class sensibilities or explained for an imagined middle-class reader. This squashes the multiplicity of working-class experience into a few standard tropes: the misery memoir, the escape, the clever boy or girl “done good”.

As writer Natasha Carthew, who grew up in a single-parent family in a council house in rural Cornwall, says: “Protagonists don’t have to be addicts or alcoholics or victims in some way, they could just be working class and what that means to us all in its compassionate impulsive big-hearted ways.”

¶

This question of class takes yet another turn when a working-class writer gets published and has some degree of success. Over time, you may accumulate the stuff of the middle-class life: the house, the car, a nice handbag (I like handbags). Your Brummie accent might have the corners shaved off in certain company. Are you still working class? Or have you hopped over the tracks?

Most published writers I speak to from a working-class background experience this anxiety. For Lisa Blower, creative writing lecturer at Bangor University and author of the novel Sitting Ducks, the question of whether she is still working-class enough to write working-class fiction makes her “blood red and boiling to boot”. “It’s like saying you shouldn’t write crime if you’re not a serial killer,” she says. “It’s one thing defending the book’s content if it’s controversial or inauthentic, but having to validate your authorial status suggests a homogenised culture of one true experience – and that’s some pre-imagined version from the outside looking in.”

Blower grew up in Stoke-on-Trent in a working-class household with access to books, music and stories. “And those are the stories I still hear. People told them without realising they were stories. I never set out to specifically write ‘working-class fiction’; that’s a label I get given because there’s political tension in my writing, which I would argue is more to do with identity.”

She continues: “All too often, popular culture, including literature, neglects to reflect working-class life in its diversity. It’s easy to depict rich and poor, north and south, while undermining those who exist in-between. Working-class writing is simply reflecting lives, to paraphrase Alan Bennett, that are generally happening elsewhere.”

For all her social mobility, Blower’s novel Sitting Ducks still took two years to find a publisher. “I’d be told it was an inauthentic voice, that I should rewrite it from the point of view of the seven-year-old daughter to make the politics more palatable when it was too angry. But I believe in what I want to say. So I’m belligerent rather than frustrated, because there has never been a more essential time to get working-class stories heard.”

¶

Dead Ink has recently published the anthology Know Your Place which features a collection of essays from working-class writers. “This sense of unworthiness and hostility has stuck with me all my life,” writes Lee Rourke in his essay Hop-Picking: Forging a Path in the Edgelands of Fiction. Carmen Marcus, a writer from North Yorkshire, tells me that she “killed her accent” to be taken seriously, before realising that there are thousands of writers in the same position. She has now formed a collective to support other working-class writers like herself.

Within the mainstream publishing industry, too, there is appetite for change. Penguin has launched Write Now, an initiative to find new writers from diverse backgrounds; it no longer requires its new job applicants to have degrees. Many other publishers now pay their interns and provide traineeships. I am editing an anthology of working-class memoirs called Common People, for the crowdfunding publisher Unbound, with contributions from Malorie Blackman, Damian Barr, Louise Doughty, Cathy Rentzenbrink, Stuart Maconie, Jill Dawson and Tony Walsh, people who might not immediately spring to mind when you think of the working-class writer. Sixteen unknown writers will be published alongside them.

Working-class stories are not always tales of the underprivileged and dispossessed – these are narratives rich in barbed humour, their technique and vernacular reflecting the depth and texture of working-class life, the joy and sorrow, the solidarity and the differences, the everyday wisdom and poetry of the woman at the bus-stop, the waiter, the hairdresser.

I couldn’t end this piece without talking about the upper- or middle-class white men and women who wrote the classics and some of the masterpieces of literature. I love their writing, respect – no, envy – their skill and craft, and cherish those books that tell us so much about the world and what it is to be human. These are works that, as Italo Calvino says, haven’t finished saying what they have to say. This isn’t a plea to take them off the shelf. It isn’t a case of us or them; it’s a case of us and them. Shove all those other books up a bit and make room on the shelf for stories from all of the communities that make up the working class. We do literature and ourselves a disservice if we don’t.

- Common People: An Anthology of Working Class Writers, edited by Kit de Waal, is crowdfunded at unbound.com.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion