(I really tried to come up with some awful pun for the title of this post… Something like “I.C.E. is Not So Cool”. But then I just couldn’t pull the trigger…)

From a February 16th article on TorrentFreak:

The US Government has yet again shuttered several domain names this week. The Department of Justice and Homeland Security’s ICE office proudly announced that they had seized domains related to counterfeit goods and child pornography. What they failed to mention, however, is that one of the targeted domains belongs to a free DNS provider, and that 84,000 websites were wrongfully accused of links to child pornography crimes.

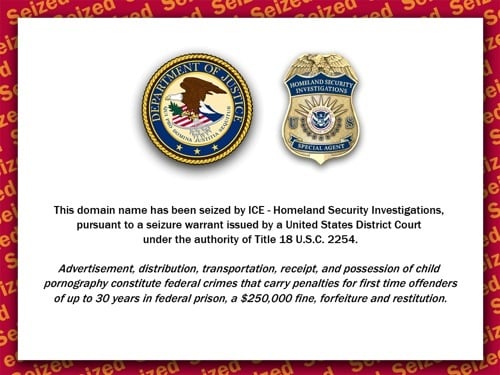

So some official at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.) division of the Department of Homeland Security is charged with shutting down websites that are found to be trafficking in counterfeit goods or child pornography. Ten such sites are identified, and he gets a court order to take them offline. But then – OOPS! A fat-fingered typo occurs and he accidentally knocks out 84,000 legitimate, innocent websites in the process. For several days, any attempt to visit one of those sites was met with this lovely image, branding the site owner as a trafficker in kiddie porn:

This story rapidly made the rounds in techie news circles, but I haven’t seen any coverage of it in the general interest press, much less the arts and culture media. Here’s why you should care:

As a content producer and/or distributor, you can be shut down without any kind of authentic due process. This is true whether or not you’re the victim of an unfortunate typo. When I.C.E. wants to shut someone down, they’re required to get a court order, but there’s no opportunity for the accused to offer any kind of defense, and there certainly isn’t a jury of one’s peers. But the important thing is to take these sickos offline ASAP, right? Well, sort of. It’s not always that simple, though, which is why we have a judicial system in the first place.

Modern technology hugely amplifies otherwise modest human error. In the internet age, tasks that once would have taken huge amounts of manual labor can be executed with a single keystroke. Generally speaking this is a wonderful thing, and I for one owe my career to this phenomenon. At the same time, this amplification of individual human impact warrants extraordinary quality control mechanisms, since the consequences of a small mistaek can be enormous. Clearly, I.C.E.’s procedures lack any kind of reasonable checks and balances to ensure that their enforcement actions don’t inflict enormous collateral damage.

Music and movies are next. The US Senate is currently considering an insidious piece of legislation called the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA). This bill would expand I.C.E.’s domain-shutdown mandate to cover sites accused of unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials (e.g., music and movies). It’s supported by a number of organizations that  are ostensibly interested in protecting the rights (and income) of content creators: the Motion Picture Association of America, the Screen Actors Guild, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, and Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States.

It’s not hard to imagine the myriad ways COICA can go wrong. It’s a blunt instrument, employed by people who presumably have little or no subject-matter expertise (either on the content itself or the nuances of copyright law and fair use), with the same lack of due process and vulnerability to human error that exists with I.C.E.’s current activities. Furthermore, in practice it’s likely to be enforced primarily in response to requests from attorneys at large media companies. Senate sponsor Pat Leahy has proposed an amendment which is intended to address some of these concerns, but it doesn’t go nearly far enough.

I believe in the importance, value, and legitimacy of copyright. I pay for the music I listen to and the movies I watch, despite having ample opportunity not to do so. But in our zeal to protect the interests of artists and content distributors, let’s keep the old saw in mind: “first, do no harm.”

It seems to me, though, that there are some unspoken assumptions in this debate that are worth bringing to the surface. I haven’t yet heard anyone argue that there’s an oversupply of art, just that there’s an oversupply of non-profit arts organizations. The real problem is that our industry still worships the cult of the eternal institution. Repeat after me: corporations, including non-profits, are perpetual entities that are expected to outlast the participation of their founders. Not every idea – no matter how brilliant, creative, lucrative, etc. – warrants forming a new perpetual entity just to house it. Lincoln Center is not the only valid model for eager young MFA grads to aspire to. In fact, it’s a rather expensive, inflexible one, and it’s particularly ill-suited to artists whose creative interests lie on both sides of the conventional boundary between commercial and non-profit fare.

It seems to me, though, that there are some unspoken assumptions in this debate that are worth bringing to the surface. I haven’t yet heard anyone argue that there’s an oversupply of art, just that there’s an oversupply of non-profit arts organizations. The real problem is that our industry still worships the cult of the eternal institution. Repeat after me: corporations, including non-profits, are perpetual entities that are expected to outlast the participation of their founders. Not every idea – no matter how brilliant, creative, lucrative, etc. – warrants forming a new perpetual entity just to house it. Lincoln Center is not the only valid model for eager young MFA grads to aspire to. In fact, it’s a rather expensive, inflexible one, and it’s particularly ill-suited to artists whose creative interests lie on both sides of the conventional boundary between commercial and non-profit fare.