There was something dramatically overwrought about first the publication and then the pulping of Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography. The themes, the moral issues and the ironies involved in the rise and fall of both the book and its author were all so conspicuously pointed, as if they had been conceived by a hack writer seeking to pay homage to a more skilled documenter of cultural conflict like, say, Roth himself.

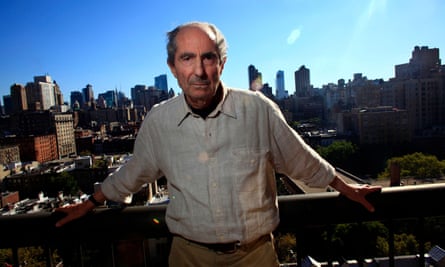

First there was Bailey’s all-too-evident pride, bordering on hubris, at having landed the Roth gig. The last giant of American letters, Roth was in many respects a biographer’s dream – a semi-reclusive enigma with a rich and disputed private life, a trove of disguised autobiographical fiction to unpack, and a genuine literary celebrity who was revered as a genius and reviled as a misogynist.

The problem was, like many novelists before him, Roth – all too aware of the divergent opinions – wanted to control his legacy. So he first recruited as his biographer a friend he thought pliable, Ross Miller, nephew of the playwright Arthur, but the arrangement twice came to an end after Roth criticised his research methods.

Roth even wrote a full-length book entitled Notes for My Biographer, mostly devoted to rebutting the allegations made by Roth’s former wife Claire Bloom in her incendiary memoir Leaving A Doll’s House. He considered publishing the book then decided to keep it as an aid for his biographer. Roth offered the vacant role to several other friends, including the respected biographers Hermione Lee and Judith Thurman, neither of whom were available. In 2012, Bailey entered the picture. He didn’t know Roth, but he’d written three highly praised literary biographies, including works on Richard Yates and John Cheever.

Roth quizzed Bailey on why he should entrust his life, as it were, to a “gentile from Oklahoma”. According to the biographer, what sealed the deal was that, when Roth showed him a photograph album of his old girlfriends, Bailey mentioned Ali MacGraw, who starred in the film adaptation of Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus. Roth told the younger man that he could have dated her. When Bailey demanded to know why he hadn’t, Roth replied: “You’re hired.”

Such anecdotal details would later take on smoking gun significance.

Bailey’s 900-page study was finally published earlier this year, three years after Roth’s death, and it garnered largely laudatory reviews – Cynthia Ozick called it a “narrative masterwork” in the New York Times. The biographer couldn’t hide his elation, appearing in interviews like a man who was joyfully in awe of his own achievement.

But there were ominous clouds gathering. A review in the New Republic depicted Roth as a bully, especially towards women, and a spiteful obsessive. Although the target was Roth, the reviewer, the magazine’s literary editor, Laura Marsh, noted that “In Bailey, Roth found a biographer who is exceptionally attuned to his grievances and rarely challenges his moral accounting.”

Ruth Franklin, biographer of the gothic horror writer Shirley Jackson, agrees. She was admonished by Bailey for being too feminist in her treatment of Jackson. As a result she declined to review the Roth biography, but she told me: “The way that Bailey treats both of his [Roth’s] wives in the narrative is blatantly one-sided.”

Again, if it had been in a novel, narrative alarm bells would have been loudly ringing. A month later, WW Norton, publisher of the biography in the US, announced that it was temporarily suspending the book’s shipping and promotion, as it emerged that Bailey faced allegations of sexual harassment and abuse, which he denies. A week later Norton confirmed that it was withdrawing the book from sale and pulping remaining copies. And Bailey’s representation was also terminated by his agency, the Story Factory.

Like almost everyone else involved, Norton does not want to discuss its decision. Franklin, who is herself published by Norton, remains confused by the move. “I am not sure what they were trying to accomplish with this,” she says.

Laura Marsh was also surprised by Norton.

“I don’t know if it’s unprecedented,” she says, “but certainly there aren’t a lot of other examples I can think of of a publisher doing that. And none of the people who spoke to the newspapers called [for the book’s withdrawal].”

But she doesn’t necessarily think the publisher was wrong. “It is probably too soon to have an opinion on whether it was the right decision,” she says.

The man who had originally commissioned Bailey, the vice-president of Norton, Matt Weiland, wrote to me that he was “leaving it to others to speak about these matters”.

The book was then snapped up in America by Skyhorse Publishing, which is also the publisher of Woody Allen’s autobiography, Apropos of Nothing, which was dropped by Hachette in the US after a staff walkout. Bailey’s UK publisher, Vintage, announced that it was not withdrawing the book but would continue “assessing the situation closely”.

No one at Vintage or its parent company Penguin Random House wants to say any more than that. Editors and publishers at PRH, including one who has left, won’t even speak off the record. One agent told me that she’d heard that the decision was announced to staff in an online meeting that came with a trigger warning.

What’s clear from the silence is that withdrawing the book, and also not withdrawing it, are hugely sensitive issues. They plug into a range of contemporary debates about censorship, moral responsibility, freedom of expression, corporate governance, social justice, due process, workplace safety, and the ongoing critique of so-called toxic masculinity, among others.

It’s for these reasons, says a leading agent, that the book’s withdrawal “has put everyone [in the industry] on edge. It sets a precedent and adds increased pressure in an already fraught atmosphere around issues of cancellation.”

One publisher, who asked to remain anonymous, describes a climate in which younger members of publishing staff, emboldened by social justice campaigns and their own sense of responsibility and power, are driving organisations to make symbolic stands.

“It’s an absolute intergenerational conflict in media organisations between the under-40s and the over-40s,” he says. “The distinction really is between social media natives who don’t really treasure free speech because they’ve had a lifetime’s worth and think it’s overrated, and people of an older generation who didn’t have access to the means of cultural production and needed the patronage of newspapers and publishing houses to get their voices heard.”

He believes that these factors played a part in Allen’s book cancellation at Hachette, and led Simon & Schuster to be accused of “perpetuating white supremacy” for striking a deal to publish former vice-president Mike Pence. Simon & Schuster successfully resisted internal pressure to drop Pence, just as Penguin in the UK did not give into demands by some of its staff to tear up its contract with the controversial academic and author Jordan Peterson.

In Allen’s case the picture was complicated by the fact that Hachette was also the publisher of his son and most outspoken critic, Ronan Farrow, something of a hero to millennials for his work on exposing sexual abuse in the film industry. But what does Bailey’s story tell us about the battle lines and what kind of benchmark does the book’s withdrawal establish?

Many, including Laura Marsh, espouse the theory that the withdrawal was Norton’s belated attempt to overcompensate for an earlier error. The most serious accusation against Bailey is one of rape, and it stems from a meeting between Bailey, who is 57, and a publishing executive named Valentina Rice, 47, that took place at the home of the New York Times literary critic Dwight Garner in 2015. Both Bailey and Rice stayed over and, according to Rice’s account, Bailey entered her room and had non-consensual sex with her. The biographer has strenuously denied this version of events.

Rice decided not to report the incident but three years later, galvanised by the #MeToo movement, she sent an email, under a pseudonym, to the president of Norton, Julia Reidhead, accusing Bailey of rape. Reidhead did not respond, but a week later Bailey wrote to Rice, having been forwarded the pseudonymous email, and rebutted her allegations while pleading with her to think of his wife and young daughter, because “such a rumour,” he wrote, “even untrue, would destroy them.”

It seems that Norton did ask Bailey about the allegations but he said they were false, and they left it there, without getting back to the woman who claimed to be the victim.

“Norton made a big mistake there,” says another agent. “They should have written back [to the woman] in the first instance, clearly stating that it was a criminal matter which needed to be investigated by the appropriate authorities.”

So when the rape accusation surfaced after the Roth biography’s publication, along with multiple claims that Bailey had inappropriate relations with his students when he was a schoolteacher, and the allegation that he raped his former student Eve Crawford Peyton in 2003, Norton reacted.

There is obviously an important principle of due process and innocence until proven guilty at stake here. Even if the accusations relating to Bailey were all true – and he has denied that they are – should that affect our appreciation of his work, and whether or not it ought to be withdrawn from sale? If, for example, the designer of a vacuum cleaner was discovered to have a history of sexual abuse, would that vacuum cleaner be taken off the shelves?

Of course a book is a different kind of object or artefact from a domestic appliance, but does it occupy a category that is indivisible from its creator? It’s not as though Bailey’s book was a memoir about his sexual conquests, but it was a book that discusses someone else’s sexual conquests – Roth’s – and in terms that might often seem loaded in Roth’s favour. Would the book have been withdrawn had its subject been Henry James or Emily Dickinson, to name two famously sexually restrained authors?

“It looks as though they’ve got two for one here,” says British novelist Howard Jacobson. “In a curious kind of way it’s been a means of censoring Philip Roth while not censoring Philip Roth.”

Though a longtime admirer of Roth’s writing, Jacobson has no wish to read the biography, having spent too much time in Roth’s head over the past 50 years.

“I met him a couple of times,” he says. “He was horrible the whole time. Everything I ever heard about him suggests he was a thoroughly horrible man.”

But about Norton’s decision to respond to the accusations against Bailey by withdrawing the book, Jacobson is adamant: “I don’t care what he is accused of, the man could be rotting in prison for having committed every crime under the sun, including going on anti-Israel marches which of course is the worst crime of all in my book, and they’re still entitled to write a book and they’re still entitled to have that book read. And it’s not the job of the publisher to censor the life of the person who writes the book.”

Jacobson’s position is a version of the traditional free speech case, in which the art and the artist are never conflated, and the moral judgment of the latter is not placed on the former. The merits of this argument are not hard to see. It means that students of history can read Mein Kampf without it meaning that they are supporters of Adolf Hitler. And the bookshelves don’t have to be filleted of books by various disreputable, unpleasant, criminal or, by today’s standards, morally reproachable people.

To take just one example, Darkness At Noon is seen as a classic work of fiction, hauntingly capturing the terror of the Soviet purges. Its author, Arthur Koestler, was accused of being a serial rapist whose victims included Jill Craigie, the feminist film-maker and wife of former Labour leader Michael Foot. It shows how times have changed that when Craigie’s accusation surfaced at the turn of the century in David Cesarani’s study of Koestler, the author Frederic Raphael argued that Craigie knew the novelist’s character, and may “have been excited by the risk[s]” she was taking.

“The abuse of women was (if it is not still) a certificate of virility in many great men,” wrote Raphael, concluding: “If we dispraise famous men, who is to be spared?”

The latter sentiment was echoed by another British novelist, who reserved his real ire for Cesarani’s prurience and biographical opportunism. Such attitudes foreshadowed Roth’s own growing preoccupation with posthumous reassessment, which he fictionalised in 2007’s Exit Ghost. His alter ego Nathan Zuckerman takes a sensationalist biographer to task for exposing a novelist named Lonoff’s incestuous affair with his half-sister:

“So you’re going to redeem Lonoff’s reputation as a writer by ruining it as a man. Replace the genius of the genius with the secret of the genius.”

A bust of Koestler was removed from display at Edinburgh University, but no one considered – then or now – removing his books. The truth is that any kind of retrospective moral inventory of authors would leave libraries and backlists with a lot of empty spaces. In philosophy, Martin Heidegger was a Nazi and Louis Althusser killed his wife. In American literature, William Burroughs killed his wife and Norman Mailer stabbed his second wife, almost killing her, at a party.

The implication in the Vintage statement about assessing the situation was that if the story developed, its stance might change, and Bailey’s book could be withdrawn.

I’m told by a number of people in publishing that this would be a popular move with many of those under 40 in the industry, who often feel underrepresented in corporate decisions. But if that is the case, I could find no young publisher who was prepared to voice that opinion, even anonymously, and I approached half a dozen radical voices as well as the Society of Young Publishers. A typical response I received read: “While I have my own opinions on this, I do not feel it is my place to comment.”

It’s as if these supposed would-be book censors are said to be everywhere and yet, like a chimera, on closer inspection vanish into thin air. Nonetheless one agent is so despairing of the censorial attitudes she regularly encounters that she told me that, along with unconscious bias training, she would like to see young recruits given training in civil liberties.

“You know,” she says, “freedom of speech and the marketplace of ideas. They don’t seem to have any respect for these things.”

Toby Mundy is a former publisher who now runs his own agency. He lets out a knowing laugh when I mention this suggestion.

“Our industry has been right to promote diversity,” he says, “not just within organisations but also in terms of the voices being heard. The mistake has been not to combine diversity with pluralism.”

The counterargument is that any kind of pluralism that involves white supremacy and misogyny is unacceptable – but, of course, who defines what constitutes these terms? In any case, surely a publishing house isn’t under obligation to buy books by people of whose opinions and character it disapproves. That’s not censorship; it’s simply the exercise of discriminating taste.

Jacobson agrees, but argues that if the taste is shaped by a “monotonous chorus of young people” then it’s unlikely to allow for anything but the most tightly prescribed viewpoints.

“If I was a publisher now,” he says, “I would say the whole lot of you need a course. This is what literature does. If it displeases you, good. Its job is not to make you feel better or to appeal to you. The fact that you don’t like it is 100% irrelevant.”

That’s probably not a message that is going to be widely adopted as policy. Ruth Franklin suggests that the most egregious problem with cancellation is the arbitrariness of its enforcement. “There’s no way to flush out every writer who’s committed a wrongdoing or a crime, so the people who are getting punished for it are those who are unfortunate enough to get caught.”

That’s often the way with crime and punishment, but Franklin believes that it really comes down to economics, and the potential comeback. “I think it’s a fear of reprisals for supporting somebody who does not appear to be worthy of our support.”

Indeed the key factor in publishing decisions when it comes to controversy, as elsewhere in life, is often money. Had Peterson been a mid-ranking author rather than a bestseller, the internal protests against him at PRH would probably have had much more chance of success. The same can be said of JK Rowling, whose tweeting habits regarding transgender and gender critical issues have led to her being denounced by a generation of appalled fans, including some of the actors she’d helped make famous.

But her publisher, Hachette, which had swiftly dropped Allen, told its staff that it could not refuse to work on her books, because it would run contrary to their belief in free speech. As one publisher put it: “There’s always a commercial decision to be made at the bottom of every publication. You’re always measuring the cost, not just the financial cost of producing a book, paying in advance, promoting it, distributing it, but also the cost to your staff of servicing the author and the difficulty of that.”

In theory, rejected or dropped authors can always go somewhere else. There is the plurality, after all, of the marketplace. In America, there is a wide political spectrum of publishing houses, although the most esteemed tend to be liberal. In the UK, it’s a slightly narrower environment, and the choice is more often between well-known publishers and obscure outfits just a step up from self-publishing. The freedom to step outside the liberal mainstream is curtailed only by the desire to be noticed and, perhaps, paid.

Will all the allegations affect Bailey’s ability to find a major publisher for whatever his next work is? As another publisher said to me: “If he sent in a proposal tomorrow for a biography of Don DeLillo, I don’t think many publishers would be rushing to buy it.”

Bailey has apparently returned to Oklahoma, the state in which he grew up and about which he wrote, rather unfavourably, in his memoir The Splendid Things We Planned, which Norton has also withdrawn. In that book he detailed a difficult relationship he had with his brother, Scott, an alcoholic and heroin user, who rebelled against his bourgeois background and set out on an increasingly dysfunctional path, leading eventually to suicide.

“You’re gonna be just like me,” a drunken Scott warned his younger brother at one point. “You’re gonna be worse.”

Bailey has always had the humility to refer to himself as a flawed person, though what the flaws refer to beyond his own youthful tendency to get drunk and misbehave, he hasn’t spelled out. He has told friends that, whatever his faults, he is avowedly not a rapist.

Somewhere behind all the accusations and denials, there remains a 900-page biography of Philip Roth. It’s a fascinating if depressing read, because despite Bailey’s obvious admiration for his subject, Roth comes across as a vain, prickly and ultimately lonely man. Having devoted himself first to literature and second to the sexual pursuit of women, he ended up being terrified of what his posthumous reputation would be.

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me,” he told Bailey. “Just make me interesting.”

The pitch-black irony is that it’s the biographer who is in need of rehabilitation, and all his considerable literary efforts to do justice to Roth as a brilliant and complicated human being have been somewhat undermined by the allegations about his own behaviour towards women. Roth’s writerly injunction to himself was to “let the repellent in”, by which he meant not to avoid the dark side of human nature. The accusation against Bailey is that he let the repellent out.

One effect of this strange blurring or complicity between biographer and subject is to make the book compelling evidence in the case that says Roth, notwithstanding his respectful friendships with and generosity towards a number of formidable females, was a man who was cruel and controlling to rather too many women.

It’s a book, in other words, that for many reasons, not all of them edifying, deserves to be read rather than withdrawn. One of them is that it tells us a great deal about its subject but also quite a lot about its author too.