The Small Island Where 500 People Speak Nine Different Languages

Its inhabitants can understand each other thanks to a peculiar linguistic phenomenon.

On South Goulburn Island, a small, forested isle off Australia’s northern coast, a settlement called Warruwi Community consists of some 500 people who speak among themselves around nine different languages. This is one of the last places in Australia—and probably the world—where so many indigenous languages exist together. There’s the Mawng language, but also one called Bininj Kunwok and another called Yolngu-Matha, and Burarra, Ndjébbana and Na-kara, Kunbarlang, Iwaidja, Torres Strait Creole, and English.

None of these languages, except English, is spoken by more than a few thousand people. Several, such as Ndjébbana and Mawng, are spoken by groups numbering in the hundreds. For all these individuals to understand one another, one might expect South Goulburn to be an island of polyglots, or a place where residents have hashed out a pidgin to share, like a sort of linguistic stone soup. Rather, they just talk to one another in their own language or languages, which they can do because everyone else understands some or all of the languages but doesn’t speak them.

This arrangement, which linguists call “receptive multilingualism,” shows up all around the world. In some places, it’s accidental. Many English-speaking Anglos who live in U.S. border states, for instance, can read and comprehend quite a bit of Spanish from being exposed to it. And countless immigrant children learn to speak the language of their host country while retaining the ability to understand their parents’ languages. In other places, receptive multilingualism is a work-around for temporary situations. But at Warruwi Community, it plays a special role.

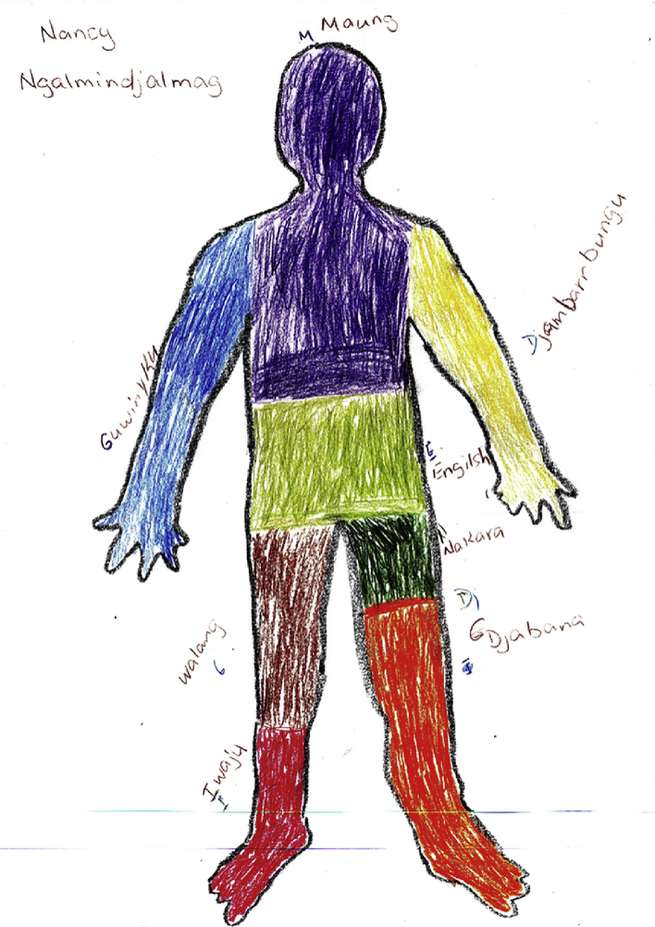

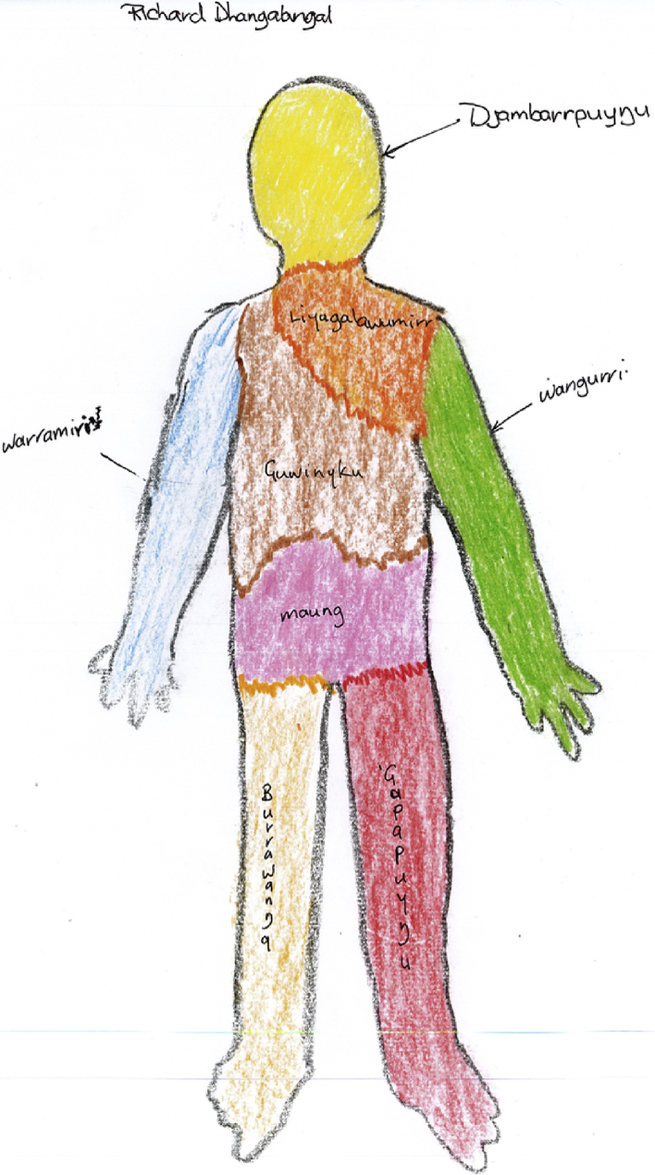

Ruth Singer, a linguist at the Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity Project of the Australian National University, realized this by chance, and wrote about receptive multilingualism at Warruwi Community recently in the journal Language and Communication. In 2006, for one of her trips for fieldwork on South Goulburn, Singer and her husband had a Toyota truck shipped from Darwin by boat. Though the island’s not very big, there aren’t many cars, so having one is a social lubricant. Singer and her husband became friends with a local married couple, Nancy Ngalmindjalmag and Richard Dhangalangal, who had a boat and trailer but no car, and the two couples ended up going fishing and hunting, and digging up turtle eggs on the beach. That’s when Singer noticed that Nancy always spoke to Richard in Mawng, but Richard always replied in Yolngu-Matha, even though Nancy also spoke fluent Yolngu-Matha.

“Once I started to work on multilingualism and tuned my ear into how people were using different languages,” Singer wrote in an email, “I began to hear receptive-multilingualism conversations all over Warruwi, like between two men working on fixing a fence, or between two people at the shop.”

There are a variety of explanations for this, Singer says. In the case of her married friends, Richard didn’t speak Mawng, because he wasn’t originally from Warruwi Community. If he did so, it might be perceived as a challenge to rules that exclude outsiders from claiming certain rights. Also, Yolngu-Matha has more speakers, and those speakers tend to be less multilingual than speakers of smaller languages.

More broadly, people at Warruwi Community avoid simply switching to a shared language because there are social and personal costs of doing so. Some families insist that their children speak only their language, usually their father’s. Languages are associated with particular pieces of land or territory on the island, and clans claim ownership of that land, so languages are also considered to be owned by clans. One can only speak the languages one has a right to speak—and breaking this restriction can be seen as a sign of hostility.

Still, neither restriction applies to understanding a language—or as Nancy put it in an interview with Singer, to “hearing” it. Singer suspects that receptive multilingualism in Australia has been around for a long time. The phenomenon was noted by some of the earliest European settlers on late 18th-century expeditions into the Australian interior. “Although our natives and the strangers conversed on a par, and understood each other perfectly, yet they spoke different dialects of the same language,” one settler wrote in a journal.

While Australia isn’t the only place in the world where receptive multilingualism happens, one thing that makes it different in Warruwi is that those receptive skills have a status as real proficiencies. Where the academic foreign-language field tends to see such skills as language half-learned, as an incomplete—or even worse, failed—acquisition, at Warruwi a person can claim receptive skills in a language as part of their repertoire. The Anglos in Texas aren’t likely to put “understands Spanish” on a job résumé, while the immigrant children might be embarrassed that they can’t speak their parents’ languages. Another difference is that people at Warruwi Community don’t see receptive skills as a path to spoken abilities. Singer’s friend Richard Dhangalangal, for example, has lived most of his life with speakers of Mawng, which he understands very well, but no one expects him to start speaking it.

Receptive multilingualism has been institutionalized in some places. In Switzerland, a country with four official languages (from two different language families), receptive multilingualism has been built into the educational system, such that children learn a local language, a second national language, and English from an early age. In principle, this should allow everyone to understand everyone else. But a 2009 study showed considerable monolingualism among Swiss citizens; Italian speakers tended to be the most multilingual and French speakers the least. Moreover, each group of speakers possessed strong negative attitudes about the others. Just as in Warruwi Community, social factors and ideas about language shape the life of many languages in places like Switzerland.

But even someone in Switzerland might consider the status of understanding-without-speaking in Australia to be no big deal, given that many people in Europe tend to have related languages in their repertoire (think Romance, Germanic, and Slavic languages). This allows them to draw on cognate vocabulary and grammatical structures for passive understanding. The languages from Warruwi Community, by contrast, come from six different language families and aren’t mutually intelligible, so those clusters of receptive skills amount to something quite sophisticated. Not enough is known about receptive multilingualism to know how many languages someone could understand but not speak.

Whether in Switzerland or at Warruwi Community, one advantage of receptive multilingualism is that people can express who they are and where they’re from without forcing other people to be that thing, too. According to Singer, this creates social stability at Warruwi Community, because all the groups feel comfortable and confident with their identities. “The social and linguistic diversity at Warruwi is seen as essential to social harmony rather than as a barrier, underscoring the need for people to assert diverse identities instead of everyone identifying as the same,” she writes. “When there’s no larger hierarchical social structure such as chiefdom, kingdom, or nation, maintaining the peace is no easy matter.”

One option for keeping the linguistic peace in other parts of the world is for everyone to opt into speaking a language they all share, perhaps even a lingua franca. This is called “accommodation,” which at its core is about reducing differences among people. But in some places in the world, accommodation is dis-preferred, even unthinkable. In the case of Warruwi Community, Singer notes that people who stake a claim to the community (and by extension its language) would be unwilling to speak another language.

And that’s one lesson to be learned from receptive multilingualism at Warruwi Community: Small indigenous groups are surprisingly complex, socially and linguistically, and receptive multilingualism is both engine and consequence of that complexity. It may also be a key to ensuring the future of small languages as the population of speakers dwindles if more was understood about how to turn receptive abilities in a language into being able to speak it. “If we understood receptive abilities better, we could design language teaching for these people,” Singer says, “which would make it easier for people who only understand their heritage language to start to speak it later on in life.”