What the Beatles Sounded Like Unedited

Fifty years after its debut, The White Album has been reissued to include demos and sessions, giving listeners a wider lens through which to examine the seminal work from the band.

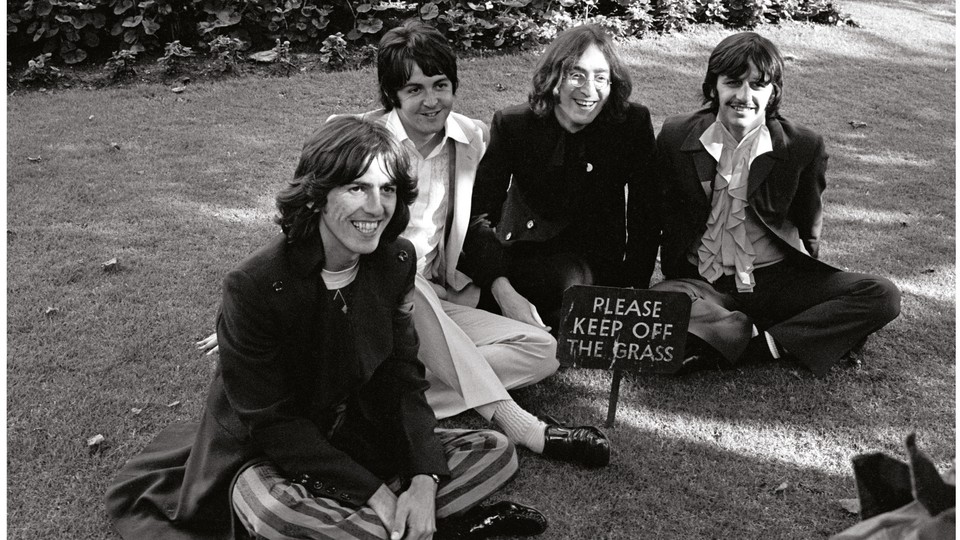

If The White Album were a concept album, the concept would be this: The world’s greatest four-piece, comprising two geniuses, one great and searching songwriter, and a magical, melancholy drummer-clown, is breaking up—it just doesn’t know it yet.

Mid-1968: The Beatles, newly returned from their trip to the Maharishi’s meditation commune in Rishikesh, India, are in an undirected and febrile state. Brian Epstein, manager and whip-cracker, is dead. At Abbey Road, where they have the run of the studio, a combination of loosey-goosey late-night scheduling, wild productivity, and ever more fussy recording habits (99 takes of a George Harrison song—never to be used, in the end—called “Not Guilty”) has worn out their greatest musical ally, their supreme editor and controller of quality, the producer George Martin. And band telepathy is out of whack: John has fallen ego-dissolvingly in love with Yoko, who goes everywhere with him.

So after the noospheric jackpot—the global love-ripple that was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—and the misfire of Magical Mystery Tour (both highly imagined, overtly conceptualized, McCartney-determined projects), The Beatles. Or The White Album, as the world knows it. Thirty songs pulling in 20 different directions, multipolar, spiking and troughing, inventing genres or exhausting them, earthy, heavenly, now dazzled by clear light, now plunging willfully into chaos and carnality.

“Long, Long, Long” is George’s waltz with God, murmuring almost shapelessly upward out of an abyss of yearning—of longing—toward the awesome punctuation of Ringo’s drum fills. John’s “Yer Blues” is cosmic gutbucket, arch primitivism, an ironic howl from the floor of the universe: “In the morning / Wanna die / In the evening / Wanna DIE.” Paul, more protean than ever, is at once the immaculate primping formalist of “Martha My Dear,” widening his eyes at the keyboard; the crystalline innocent of “I Will”; and the frazzled distortion addict of “Helter Skelter.” And Ringo sings “Good Night” with shimmering, doleful, consoling authority, an impresario of dreamland.

What, then, to make of this enormous reissue package, The Beatles (White Album) Super Deluxe Edition? Seven discs—demos, sessions, a remastering—and a great big book. Doesn’t it just magnify the sprawl, increase the luggage, barnacle with further add-ons and special features this already ungainly rattlebag of a record? Answer: Yes but no, or yes but who cares, because this is the Beatles, and we want it all.

We want the rough acoustic take of George’s “Sour Milk Sea,” a superb little pro-meditation, anti-negativity rocker that didn’t make the album: “Get out of the Sour Milk Sea / You don’t belong there / Get back to where you should be.” We want to hear John, before a run-through of “Cry Baby Cry,” muttering, “Semolina semolina pilchard green snot pie / All mixed together with a dead dog’s eye.”

We want the sensation of the Beatles playing as a band, a unit, electrically self-aware, which we get from take 19 of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” Through the lopsided chug of the verse they go (“Man in the crowd with the multicolored mirrors on his hobnail boots,” sings Lennon, in what now sounds unavoidably like a future-flash of a suicide bomber, “Lying with his eyes while his hands are busy working overtime”) before landing with beautiful, unanimous, flat-as-a-pancake, concentrically spreading heaviness on the first syllable of the chorus: “I need a FIX ’cause I’m GOING down.”

To the nuances of the remastering, by George Martin’s son Giles, I cannot speak, having vulgarized my ears with decades of heavy metal. But the selections from the sessions are glorious. Listening to a full-tilt take of “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey,” I heard it for the first time as John’s Rishikesh anthem, his unleashed-by-meditation leap into the All. There’s no madly clanging fireman’s bell on this version, but there is a fantastically wiry, preying guitar line from George, as John issues his manifesto for the embrace of metaphysical extremes: “The deeper you go / The higher you fly / The higher you fly / The deeper you go / So c’mon!”

The demos, meanwhile—recorded unplugged at George’s house in Esher, outside London—are a revelation. “Dear Prudence,” as every Beatles fan knows, is John’s other Rishikesh song, written for Mia Farrow’s sister Prudence: Part of the company, she was meditating so hard that she seemed to have lost contact with reality. On the Esher demos, John delivers the prescription: “The sun is up, the sky is blue / It’s beautiful, and so are you.” Then, continuing to strum, he starts busking, mumbling first about something that happened “in the middle of a meditation course in Rishikesh, India,” and then his voice strengthens, assuming a storyteller’s lilt: “Sooner or later,” he recounts, “she was going to go completely berserk under the care of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi … All the people around her were very worried about the girl because she was going in-saaannnnnnne …” And then he says it, simply and world-healingly, a broken Beatle using the last of his powers: “So—we sang to her.”