When Donald Trump finally spoke during this weekend’s celebration of the end of World War I, he did a boilerplate job. On Sunday, at the Suresnes American Cemetery and Memorial near Paris, Trump praised the Marines who “fought through hell to turn the tide of the war.” He told the assembled listeners that “through their sacrifice, [the Marines] ascended to peace in heaven,” and added, “It is our duty to preserve the civilization they defended, and protect the peace they so nobly gave their lives to secure one century ago.” Sure, good—the president got it together to speak. But this is the wrong way to commemorate the anniversary of the end of World War I. A better way would be to reckon with the fact that, as Slate’s Jack Hamilton said on Twitter, WWI is “really the OG modern war in terms of sending off massive amounts of young people to die for no real or clear purpose.”

The conflict that became known as the Great War had obscure and complex roots in empires and alliances. If it’s hard to explain its causes without putting students to sleep, it’s even harder to recount the way the war was conducted in a manner that gets its full scale across. A recitation of the conflict’s manifold horrors calls forth every bit of historians’ creativity, lest the reader zone out on so much death. Millions of people killed, miles of trenches, even more miles of barbed wire, the legions of disabled and widowed and orphaned. It’s all too much, and too meaningless, given the lack of a true difference in ideology between combatants and (contemporary atrocity propaganda aside) the absence of a real villain to battle.

Writing in the New Yorker, Adam Hochschild ended his review of some recent commemorative books on the armistice with a story of what happened on the last day of fighting, when everyone knew the end was coming but kept fighting anyway, “for no political or military reason whatever.” Hochschild describes the experience of the troops of the American 92nd Division—black soldiers, led by white officers, “often Southerners resentful of being given such commands.” These troops were sent “into German machine-gun fire and mustard gas” a half-hour before the armistice was meant to take effect. The division recorded 17 dead that day. Why? “The war,” Hochschild writes, “ended as senselessly as it had begun.”

After all that suffering, what “good” did the war do? The effects of the conflict on Europe are well-known: desperation, poverty, resentment, the advent of fascism, more war. (Hochschild: “It is impossible to imagine the Second World War happening without the toxic legacy of the First.”) Stateside, we exited our own briefer involvement in the conflict into some of the worst racial violence of the early 20th century. During the war, more than 6,000 dissidents who publicly criticized the draft had been arrested under the Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918, and this erosion of civil liberties continued in the postwar period.

How, then, to commemorate a useless war that shouldn’t have happened—a black hole in history? In an interview on the blog Ethics & International Affairs, given when we were beginning this anniversary period back in 2014, historian Mary Dudziak said that World War I should be commemorated by remembering “the way the American people were deeply engaged with questions of war and peace”—a contrast to today, when “one of the most unfortunate aspects of contemporary war politics is that most Americans seem content to leave the issue to leaders and experts.”

Indeed, some of the writing for and against American intervention in the war is indelible. In 1917, the young progressive journalist Randolph Bourne, who stood against American involvement until the end—even as his mentors, including John Dewey, reversed their earlier opposition, and the magazines he had written for one by one refused to publish him or folded—wrote a scathing polemic denouncing growing liberal and intellectual support for American intervention. “The pacifist is roundly scolded for refusing to face the facts and for retiring into his own world of sentimental desire,” Bourne wrote.

But is the realist, who refuses to challenge or criticize facts, entitled to any more credit than that which comes from following the line of least resistance? The realist thinks he at least can control events by linking himself to the forces that are moving. Perhaps he can. But, if it is a question of controlling war, it is difficult to see how the child on the back of a mad elephant is to be any more effective in stopping the beast than is the child who tries to stop him from the ground.

We could look back at the way people in Europe and the United States responded to the war after it ended to see how they perceived its meaning. Some artists and writers responded to their war experiences by breaking decisively, in form or in theme, with 19th-century cultural traditions—especially those that venerated abstract concepts like duty and honor when describing conflict. Brutal art like Englishman Wilfred Owen’s poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” and the German painter Otto Dix’s The Trench (I can’t link you to an image of that one, because the painting was later destroyed by the Nazis for being “degenerate”) stripped away every bit of pomp, circumstance, and patriotism from the experience of war.

In the United States, the war stoked pacifist sentiment. “Over time,” historian John Kinder writes, “millions of Americans came to believe that the Great War had served no redeeming purpose whatsoever—other than to remind them why future conflicts needed to be avoided.” Kinder’s book on the place of the disabled veteran in public conversations about the war has an unsettling chapter on the way pacifist groups used images of maimed men to mobilize anti-war sentiment in the 1920s and 1930s. Perhaps these documents are the ones that we should revisit on the centenary of such a horror. We now see, as Kinder points out, that their explicit nature was exploitative and demeaning—but in their forcefulness, the images show how serious some people were about peace, after this useless war came to a close.

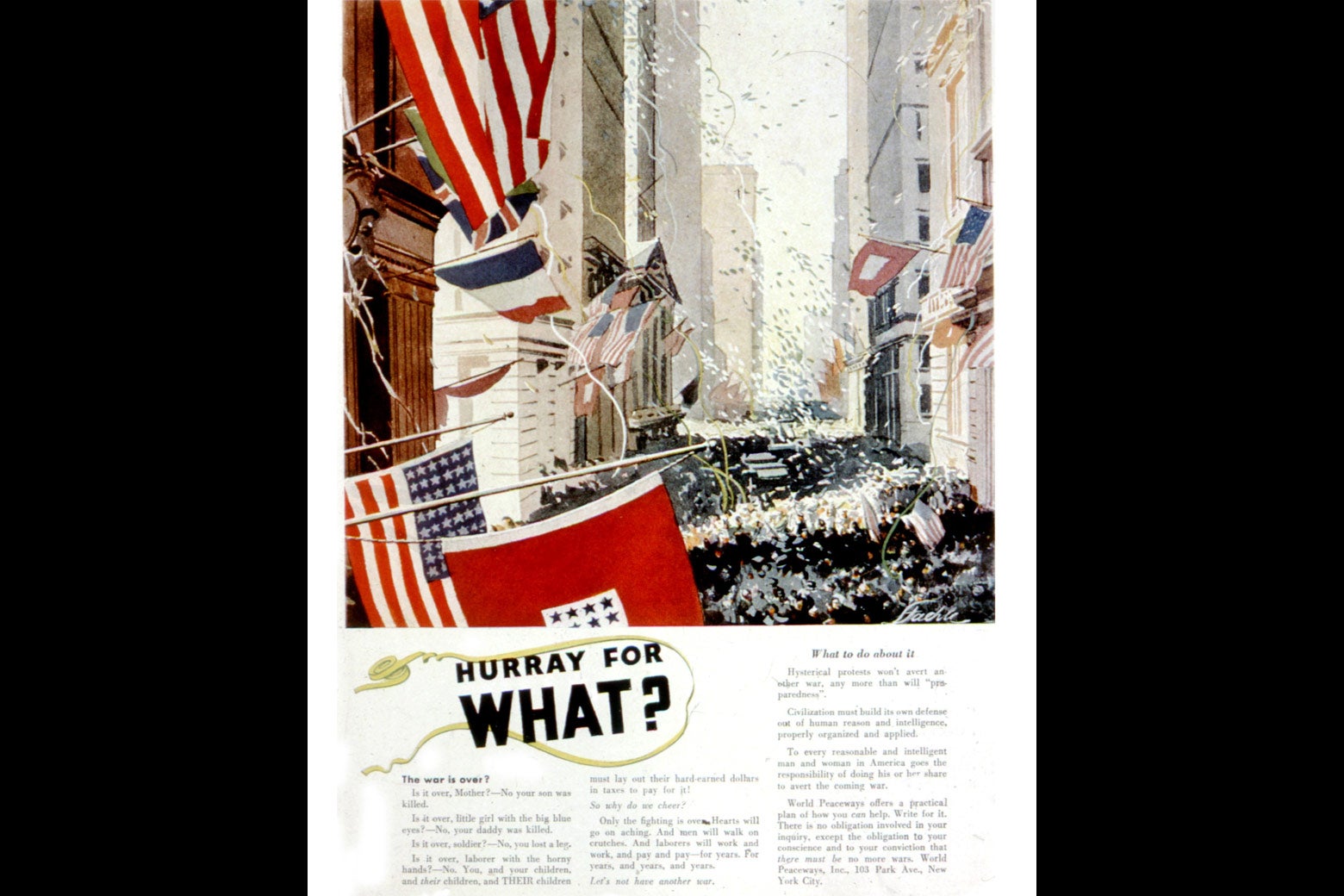

The content and style of these pacifists’ ads, posters, and books were blunt and bloody, to the point of extremely poor taste. (“Eager to debunk war’s romance,” Kinder writes, “peace groups believed that no sane young man would ever rush off to war if he truly grasped the mutilation and long-term suffering awaiting him.”) Pacifist photo books sold in Europe and the United States in the ’20s and ’30s gathered the worst images of battlefield casualties. Ads and posters, most notably those produced by the publicity-savvy group World Peaceways, which was very effective in its efforts to get these images into mainstream media, showed the worst of those injuries in full. A poster created by a student participating in a contest meant to recruit young people to the pacifist cause depicted a soldier’s face in the very moment a bullet goes through his eye, as his helmet spins off and his gloved hand flies up in protest. The poster’s slogan: “Oh God—for What!”

But the bigger shock I experienced on encountering these documents is the realization that these ads ran in big publications, and the photo books sold well. As Kinder writes, the peace movement World War I inspired in this country was a real force right up until Pearl Harbor. The war against Hitler—the “good war”—wiped American pacifism off the map for decades, especially because some small number of American anti-interventionists proved to be fascist sympathizers.

Later, the youth movements of the 1960s revived the tradition in protesting the war in Vietnam. But reading, and looking at, these documents, you realize that Dudziak is correct: Our contemporary pacifist movement and our conversation about the very nature of war and peace are now absurdly minimalist in comparison. When liberals on Twitter respond to Trump’s failure to show up at the first round of armistice commemorations with pious platitudes about the troops, remembering, and sacrifice, it feels like we’ve lost more than we can even remember.