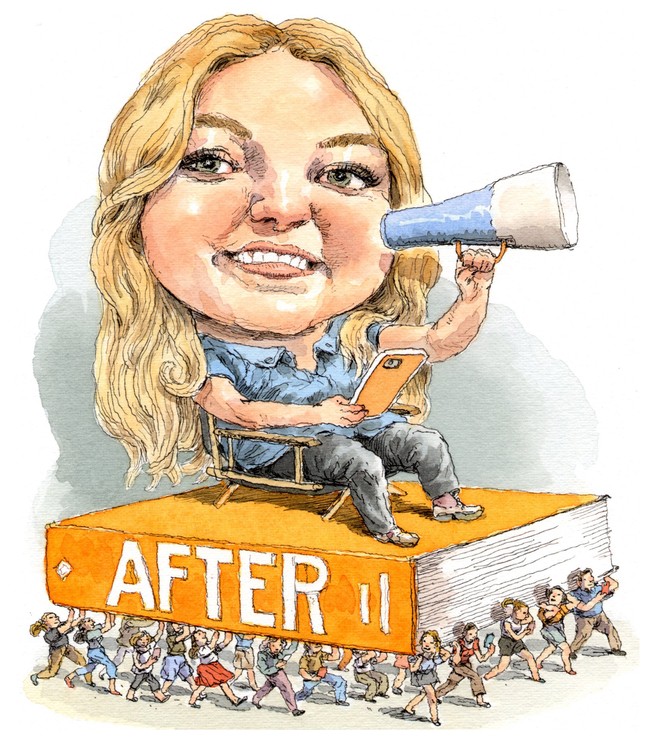

The One Direction Fan-Fiction Novel That Became a Literary Sensation

Anna Todd started writing her first book, After, on her phone. Five years later, her stories are making millions of dollars around the world.

One afternoon in the summer of 2013, Anna Todd was in the checkout line at Target when, as most of us do, she pulled out her phone. Then she propped her elbows on her shopping cart and began to type.

Todd was 24 years old and living near Fort Hood, Texas, with her husband, a soldier she had married a month after graduating high school, and their newborn, who suffered daily seizures. While caring for her son and taking online community-college courses, she helped support the family by babysitting for a neighbor and working the beauty counter at Ulta. For fun, she read. Wuthering Heights, Twilight, The Things They Carried. Since the previous fall, she’d also indulged an addiction to One Direction fan fiction—stories featuring the boy band in imagined scenarios. After blazing through all that she could find online and then tiring of waiting for updates from erratic authors (many of them teens juggling writing and school), Todd decided to attempt her own series. She called it After and wrote on her smartphone whenever she could steal a moment—while shopping for groceries, waiting to get her teeth cleaned, riding in friends’ cars. She used a pseudonym (imaginator1D) and hid her alter ego from family and friends. “My husband just thought I had a phone addiction or something,” she has said.

Without pausing to proofread, Todd uploaded a chapter a day to Wattpad, a free site that has earned a reputation as the YouTube of ebooks for its success in giving prose the social-media treatment. (Readers can chat with writers and discuss books with one another by leaving comments alongside the text as they read.) After, generously sprinkled with Pride and Prejudice allusions and oral sex, opens on Tessa Young, an innocent bookworm beginning her first day of college. It follows her torrid, tortured romance with the brooding sophomore Harry Styles—named after the One Direction heartthrob—as he initiates her into heavy drinking, heavy makeup, and heavy petting. (Aside from his accent, After’s Harry bears little resemblance to the British singer.)

By the time Todd wrote Chapter 90—of an eventual 295 chapters—her novel-in-progress had been read more than 1 million times. Multiple literary agents reached out to her, but she dismissed them as “crazy people,” figuring no legitimate professional would seek out One Direction fan fiction. Readers composed sequels starring After’s characters, uploaded video homages to the book, and—finally convincing Todd that she might have something big on her hands—chatted as Tessa and Harry on Twitter role-playing accounts. Seeing that, “I was like, ‘Holy shit,’ ” Todd once recalled. Representatives from Wattpad, which had never had such a blockbuster, contacted Todd and offered to help connect her with publishers. Before she flew to meet with Wattpad’s staff at the start-up’s Toronto headquarters, she overdrafted her bank account to pay for her passport.

Since then, Todd’s After series has been published as four volumes by Simon & Schuster in a six-figure deal, earned a spot on the New York Times best-seller list, been read nearly 1.6 billion times on Wattpad, been translated into more than 35 languages, and been adapted into a feature film, which Todd is co-producing, and which co-stars Selma Blair. (For the print and movie versions of After, Harry Styles has been renamed Hardin Scott.) On a recent book tour through Europe, cheering fans swarmed train stations waiting for Todd to disembark.

Her franchise has also helped establish Wattpad as a hub for young people drawn to its interactive approach to the written word. The site’s 65 million monthly users, who are overwhelmingly female and under 35, spend an average of 30 minutes a day reading authors who range from middle schoolers to Margaret Atwood. Building on its collaboration with Todd, Wattpad has helped hundreds of stories be adapted into books, TV shows, or films through deals with HarperCollins, NBCUniversal, Sony Pictures Television, and others; the site says it can forecast Gen Z hits and trends with far greater accuracy than industry gatekeepers acting on their gut. (Wattpad predicts that mermaids and cannibals are poised for stardom.) Netflix’s The Kissing Booth, described by an executive at the streaming company as “one of the most-watched movies in the country, and maybe in the world,” began as a Wattpad story written by a 15-year-old.

Todd sees no basis for the idea that young people have soured on books—a favorite complaint among those worried about kids these days. During my recent visit to her trailer on the film set of After, in Atlanta, she told me that an “insane” number of teachers had written to thank her for inspiring a love of reading. After discovering Tessa and Harry’s obsession with authors like Charles Dickens and F. Scott Fitzgerald, their students devoured classic literature. Todd recently lent her star power to several authors who in fan-fiction circles might be seen as underdogs: Her Italian publisher released special-edition translations of Anna Karenina, Pride and Prejudice, and Wuthering Heights prominently branded with Todd’s After-inspired logo (two interlocking hearts that form an infinity sign). “OMG PRIDE AND PREJUDICE IS LIKE AFTER,” tweeted one reader. “ANNA you are so smart I can’t even.”

Todd grew up in a trailer park in Dayton, Ohio. Her father, whom she describes as a drug addict, was stabbed to death shortly before her first birthday. She was raised by her mother, a caterer and longtime restaurant cook who also struggled with substance abuse, and her stepfather, who worked as a mechanic. Todd aspired to become a teacher or a nurse’s assistant, and remains mystified by her path to best-selling author and movie producer. “I never had any thought behind anything I did in the beginning, to be honest,” she told me.

Wattpad holds special appeal for Todd because it enables writers with backgrounds like hers—writers whose books would otherwise “never see the light of day because their names aren’t known, or they don’t have whatever following, or they don’t have experience in publishing”—to share stories that resonate with readers, regardless of whether those stories charm literary editors in New York. She worked with Simon & Schuster to publish her first book outside the After series, a retelling of Little Women called The Spring Girls. But she argues that publishing houses—“kind of an old machine”—are accelerating their decline by failing to consider a wide range of voices or offer young readers relatable protagonists. “The content that they’re pushing on young people is not what they want to read,” she told me in between takes, from her perch on a black director’s chair. “There’s so much anxiety coming from social media with teenagers that we have to give them characters that are real and that are not always happy; and that have bad parents and not great, supportive parents; and that are not going on these journeys to save the world with a bow.”

Todd understands more acutely than most writers what her readers want. She cultivates intimacy with her followers. (“You guys feel like my family,” she wrote in a Facebook post this September.) She participates in half a dozen Instagram group chats with her most die-hard fans—sneaking them behind-the-scenes footage of the After set—as well as a text-message chain with four readers she has befriended. (All of them, including Todd, got identical After-themed tattoos, and one adopted Todd’s English bulldog, Watty—named for Wattpad—when her hectic travel schedule made a pet unmanageable.) Rather than outlining her books—“it just messes up my entire story”—she prefers to “write socially.” With After, she’d review the comments on her most recent chapter and then tweak the story’s plot: If readers finished the section feeling happy, she’d throw in a twist to make them sad. If they were incensed at Harry, she’d have Tessa misbehave. “I had feedback every day, all day,” Todd said. “I always just felt like a puppet master playing with everybody’s emotions and doing this with the characters.” Wattpad is going even further by analyzing data on its stories—including sentence structure, vocabulary, readers’ comments, and popularity—in an effort to deduce exactly what makes a book succeed. In time, it may try to automate the editing process.

I started Todd’s series shortly before visiting her, and within two days, I was glassy-eyed from binge reading. Her protagonists are impulsive, thin-skinned, and racked with insecurity—just like us and people we know—and Todd, rather than tackling the soaring moral questions of high literature, lets them wallow in the petty but momentous growing pains of early adulthood: being cool, being uncool, drinking, fighting with parents, fumbling through early sexual experimentation. Tessa’s first hand job is both scintillating and extremely awkward: “I don’t know what to do so I just keep touching it, running my fingers up and down,” she admits. “I am too nervous to look at him so I keep my eyes on his growing crotch.” Todd follows Tessa and Harry’s relationship drama in what feels like real time; the blow-by-blow of each text message and fight creates a messy immediacy that heightens the pleasure of hanging out with characters as bumbling as we are.

After’s breed of graphic hyperrealism has largely been purged from young-adult fiction, says Lizzie Skurnick, a writer and editor of YA novels and the author of Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading. (Todd more specifically identifies as a “new adult” author, a burgeoning category that emerged from self-published authors’ attempts to bridge the gap between Nancy Drew and Fifty Shades of Grey.) For years, Skurnick says, books for kids and teens were read mostly by kids and teens. But Harry Potter elevated the genre into a family affair, and parental supervision did precisely what it always does to sex. “There has been a sanitization. The YA of my era—of the ’70s and ’80s—was able to be explicit, because no one was looking at it,” Skurnick told me. “Readers hunger for anything they actually experience.” In addition to featuring explicit sex scenes, After deals unflinchingly with other topics that today’s book editors and hovering parents might consider too mature for young audiences—both protagonists’ fathers are alcoholics, and Harry at one point describes witnessing his mother’s rape. Yet, as Todd points out, plenty of readers confront such situations as they exit childhood. “I’m not writing about the 1 percent of people who have this fairy-tale, amazing life,” she has said. “I’m writing about people like me, who maybe had a rough childhood.”

Todd, who has long blond hair and several tattoos dotting her upper body, was simultaneously watching her iPhone and the filming when Douglas Vasquez, the 23-year-old head of her Brazilian fan club, arrived on set. He’d traveled 30 hours to spend less than a day watching the series come to life as a film, and Todd made the producer next to her give up a seat so Vasquez could be at her side. The two studied a monitor as actors ran through what Todd calls “the most devastating scene in the movie”: Tessa bumps into friends in a bar and discovers (stop me if you’ve heard this one) that her boyfriend seduced her only to win a bet. Todd and Vasquez were soon wiping away tears. Todd rubbed his back, then leaned over him and toward a producer to suggest alternate dialogue for the scene.

Throughout the day, Todd demonstrated the uncanny ability to consider the opinions of an amorphous mass of followers as she made decisions. She talked about the actors her readers had “fancast” for the movie in the same breath as the ones selected by the filmmakers. Every other conversation was a reminder—to the on-set photographer, to the costume designer, to producers, to publicists—to snap photos for social media. While stage-managing an impromptu photo shoot with Vasquez and several actors, Todd lectured a publicist on the need to capture as much behind-the-scenes content as possible, so they could tease fans’ interest leading up to the movie’s April launch. At one point, Todd disappeared into a wardrobe trailer to help the costume designer select one of Tessa’s most iconic outfits—a maroon dress she wears to her very first frat party. The designer escorted Todd to a rack of demure dresses, all variations on the color of a grape Jolly Rancher, and produced a lace option that she and the movie’s director loved. Todd vetoed it. “It just kind of looks purple,” she said. “If this isn’t maroon, I’m going to get crucified.”

While Vasquez watched more takes of Tessa getting her heart broken, Todd’s attention drifted to other projects. She emailed with the contractor renovating the home in Los Angeles where she, her husband, and her son now live, and reviewed digital galleys of her forthcoming book, a slow-burn romance between a massage therapist and an Army veteran called The Brightest Stars.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an author in possession of a good manuscript must be in want of a publisher. Not Todd: She is posting The Brightest Stars piecemeal on Wattpad—a new chapter had gone live earlier that day—and she was preparing to self-publish the complete paperback in a few weeks. “I just wanted that control back,” she told me. (It helped that her prior book deals were generous enough that she didn’t need an advance, plus she’d sold the foreign rights to The Brightest Stars for seven figures.) In addition to redesigning the cover, Todd had opted to completely rewrite the book after soliciting feedback from her closest fans. She thrilled at making changes by sending a few texts to her editor and graphic designer rather than waiting on the creaky bureaucracy of an old machine. “When I realized that I can invest in my own marketing and do exactly what I think needs to be done—well, then it just feels like: What is the benefit of having a publisher?” Todd said.

When the crew broke for dinner, Todd ate with a fork in one hand and her phone in the other: She’d caught a formatting mistake in the galley, plus she needed to finalize plans to distribute the book at Target, and she wanted to pin down her 13-city international book tour. She had hired a manager at one point, but let him go because “he just wasn’t building me more than I could myself.” I wondered aloud how she had learned to do it all. “The internet,” she replied, then returned her focus to her phone.

This article appears in the December 2018 print edition with the headline “Crowdsourcing the Novel.”