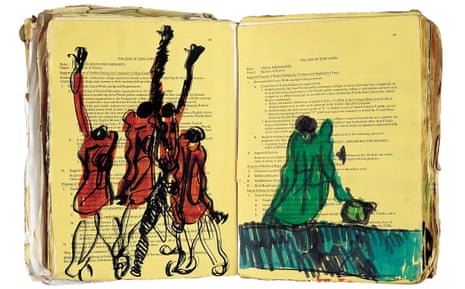

Through the 1960s and 1970s, Purvis Young, a self-taught artist from Miami, roamed the inner city streets of Overtown, scouring for cardboard, wooden crates and secondhand doors to use as canvas for his expressive paintings.

He learned the chops of art history – from Rembrandt to Van Gogh – through library books. He was often called an outsider artist and would paint trains, trucks and railroads to suggest an escape from inner city life, while his pieces told visual tales of racism, poverty and hypocrisy.

“I don’t like the luxury I see of a lot of these church people, while the world is getting worser,” he said in an interview from the 1990s. “What I say is the world is getting worser, guys pushing buggies, street people not having no jobs here in Miami, drugs kill the young, and church people riding around in luxury cars.”

Young’s legacy looks set to endure partly due to a recent acquisition of his artwork by the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. It’s from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an Atlanta-based collection of African American art from the south, boasting more than 1,000 works by roughly 160 artists, with the aim of preserving the tradition of southern art and its cultural roots.

With a noticeable shift in the museum world, there is an awakened interest for more inclusion in collections that goes beyond the typical roster of white, male artists.

“The conversations I have with museum directors around the country suggest a strong interest in working with us,” said Maxwell L Anderson, the president of Souls Grown Deep. “The artists we are bringing forward are less visible in the market and more generally, the quest to be a more representative collection on the part of museums around the country, and to be more inclusive.”

Included in their collection are works by Lonnie Holley, an artist born during the Jim Crow era who claims to have been traded for a bottle of whisky at the age of four, Mary T Smith, a Mississippi painter who detailed her rural life through whimsical paintings, and the works of the quilt makers of Gee’s Bend, a group of women – including Annie Mae Young, Mary Lee Bendolph and Arlonzia Pettway – who lived in the countryside of Boykin (known as Gee’s Bend) along the Alabama river. The women used recycled clothes and fabrics to make quilts that kept their families warm in the unheated shacks where they lived throughout the colder months.

Anderson has worked in the museum circuit for 30 years, with posts at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Indianapolis Museum of Art but with his role at Souls Grown Deep, he’s found a group aligned with his own values.

“I find it personally rewarding to be in a part of the art world that isn’t indexed to profit, collecting success, but instead, is indexed to talent, to social equity,” he said. “Those things motivate me far more than anything else.”

Since 2016, the foundation has been engaged in conversations around acquisitions at museums. “Each museum director is operating in their own nucleus of activity,” said Anderson. “We have 10 conversations at the moment and have over 1,000 artworks. We keep an inventory on a closed website which we allow one museum to see at a time, we remove items from the list if they’re not available.”

For the acquisition from the Morgan Library and Museum, a curator reached out to the foundation’s “info@” email account. “Even though I know the Morgan’s director well, one of his curators reached out that way,” said Anderson. “We’re thrilled that degree of interest is made known, we do our best to be fair and be judicious in how we move forward with acquisitions.”

Alongside the Morgan Library & Museum, they have arranged four other acquisitions with the Brooklyn Museum, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art. The funds will go towards supporting a new paid internship program for undergraduate students of color, as well as a new grant program.

The Dallas Museum of Art acquired seven works, including one piece by Nellie Mae Rowe, a self-taught artist from Georgia who made colorful artworks from found materials like egg cartons, food trays and chewing gum as well as paint, felt-tip pens and pencil. The acquired piece is called Picking Cotton from 1981, though it is remembered by Souls Grown Deep as “what could have been called ‘What I don’t like about my life as I look back on it’”. According to the Dallas Museum of Art’s director, Agustín Arteaga, the new artworks, which also include Gee’s Bend quilts, help “reflect a wide range of voices in both our collection and programs”.

Meanwhile, the Morgan Library & Museum director, Colin B Bailey, said the drawings of Young and others they have recently acquired reflect how the institution is “working toward building a more representative collection”. He added they were “an invaluable contribution to the study of modern and contemporary drawing”, and will be shown in an exhibition in 2021.

“Museums want to be representative of this African American tradition, in general,” said Anderson, and these works join the Morgan museum’s collection of first edition books by Harlem Renaissance-era African American writers and poets, including Langston Hughes.

Though many of the artists have passed away, Anderson says the non-profit has signed up 75 artists and their families to work with the foundation. “We are a public charity, so we can’t write cheques to individuals, but we can be pursuing the improving and betterment of the quality of life of communities,” said Anderson.

The foundation signals a wider change in the art world, as more museums are changing the way they collect art.

“We see the fever of the art market up and down all the time,” said Anderson. “We see fads, how African American artists are collected, they’ve tended to be on a repeat cycle of the same artists revisited by the same galleries and museums. We hope to be part of the change to open the windows and invite more people in.”

That very change takes time, and is going against the grain of industry buzz, hot topics and blockbuster exhibit ticket sales in a time of Instagram pop-up museums and selfie mania. “We try to guard against falling into the same predictable patterns, that if you’ve heard ‘a name’, that is what you should acquire,” said Anderson. “Let’s put the merits of individual works of art and understand how they might contribute to the narrative of art history.”