Novelist Rose Tremain thinks poetry these days is overrated. “Let’s dare to say it out loud: contemporary poetry is in a rotten state,” she told the TLS this week. “Having binned all the rules, most poets seem to think that rolling out some pastry-coloured prose, adding a sprinkling of white space, then cutting it up into little shapelets will do. I’m fervently hoping for something better soon.”

Had Tremain really managed to miss the whole of modernism? After all, the modernists swore they had “binned all the rules” at or around the end of the 19th century. For anyone, much less a writer, 20th-century modernist poets are hard to miss; whether it is the sediments of Eliot or Pound, or the brilliant treasures of HD, Mina Loy or Hope Mirrlees. Had Tremain leapt over the cross-currents of the next 100 years from Tennyson to Walter de la Mare to Philip Larkin, flat-footing it on their bald, smooth verse to land on some plaintive lyrical bank of our new century?

Detractors of new poetry make judgments about craft based on conservative assumptions about poetic traditions, forms, style. But radical aesthetics have their own craft and traditions, formed from intersecting political and linguistic concerns. So this isn’t a question of craft at all. Tremain and others might more accurately say that poetry is rapidly changing. And although it has always changed, recent new voices have radically altered the landscape of poetry – for some, beyond comfortable recognition. What no one dares to say aloud is who these new poets are and why they are such a threat to the supposed status quo.

In a recent interview, poet and editor Robin Robertson also railed against current poetry, which for him divides into two extremes: “light verse” or “incomprehensible”. Robertson sits somewhere in the appalled middle, frustrated by poets seeking “likes” on social media, “driven by self-promotion and shallow narcissism”, who haven’t the time “to bother with all that pesky learning-the-craft business”. Putting aside the charge that obscurantist poets betray the purpose of language to communicate – itself an insincere and ahistorical misreading – who are these poets without craft?

At this year’s National Poetry Day I was involved in an event called the Poetry Inquisition, which sprang from Jeremy Paxman’s statement as a Forward prize judge in 2014 that poets should be publicly held to account because, in speaking only to each other, their art had “connived at its own irrelevance”. One inquisitor from the floor began his question to me by quoting Robertson’s interview to support his own attack on identity politics in poetry. What did he mean by “identity-based poetry”, I attempted to ask before he unleashed a misogynist and racist tirade, and was finally heckled quiet by the assembled crowd. What the inquisitor did not want to acknowledge was that identity-based poetry is not just the preserve of marginalised voices, but covered white, middle-class men, too. Indeed, white men have been writing identity-based poetry for centuries.

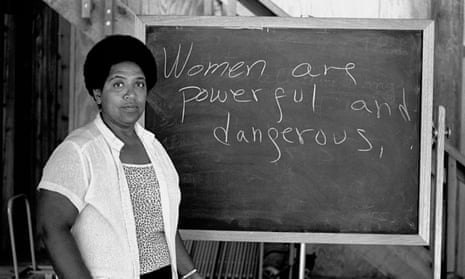

Is it coincidental that the so-called rotten state of poetry has recently begun admitting increasing numbers of diverse poets as prized citizens, rather than treating them as interlopers? A turgid defence of so-called poetic craft, based on false notions of a formal tradition, silences the possibilities offered by new voices. Audre Lorde’s 1977 essay Poetry Is Not a Luxury connects these possibilities of illuminating poetic language to tangible social activism, especially for women. What one might call craft, Lorde calls the “sterile word play” of an oppressively white, male literary canon that advocates “imagination without insight”.

Anyone excluded from the idea of literariness, which is never neutral, finds the stakes are indeed high. The presence or absence of craft is a point on which poets, critics and readers have never agreed – nor should they. Whether it’s the “shapelets” of George Herbert or Guillaume Apollinaire, or indeed the postwar Concrete poets, reactions to “newness” are an important part of an evolving culture. Yet vaguely discrediting new poetries on the basis of craft without any critical or clearly articulated evidence emboldens those among us who perceive literariness as a function of racial, educational, class or gender privilege.

We need to have a meaningful discussion about the value of our changing poetry culture, one that is open to many voices as well as rigorous and critical. But most of all, it needs to be honest. As contemporary poetry gains prominence and draws in a newly galvanised, wider readership, we must shift our critical discourse to meet it – especially in these tense political times. We need to be honest about what we’re criticising when we question a poet’s craft – and hope for something better soon.