Francesco Clemente moved to New York City in 1980 from Italy and established a studio in the then-desolate Noho. Much of the artist’s work has always explored his interest in Eastern philosophy, metaphysics, and mysticism, often refracted through his sense of America’s homegrown spiritualism — from Emerson and Thoreau to the Beat poets. But while studiously haute-bohemian, he’s hardly lived the life of a monk: His Walden often seems to involve a velvet rope.

An exhibition spanning 40 years of Clemente’s work, including portraits of the many personalities he met after moving to New York, opens November 12 at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center, set amid the manicured polo fields of Greenwich, Connecticut. (Next spring, the Brant Foundation will open its city location, in the former Walter De Maria home in the East Village, which will make Peter Brant’s collection more accessible.)

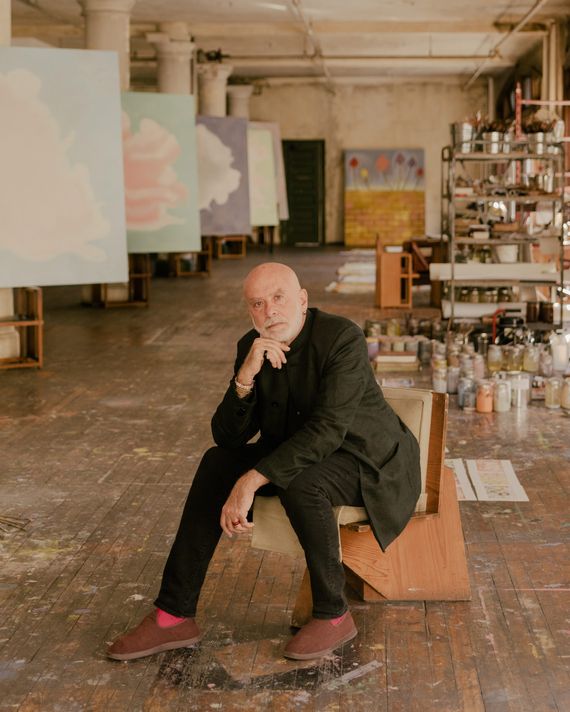

To talk about the new show, I met with Clemente at his cavernous second-floor Broadway studio, that, despite the traffic noise outside, feels a bit like an ashram or yoga studio with the industrial wood floors, exposed brick, and wafting Nag Champa incense. Affable and soft-spoken, Clemente was as impeccably dressed as ever. He and his wife, Alba — who has been depicted by him multiple times, as well as by Andy Warhol, Alex Katz, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Julian Schnabel — and their stylish children, Chiara and Nina, are as much as part of the New York social scene as they have been since his work decorated Palladium nightclub, and their creative partnership was among those recently honored at the Hirshhorn gala.

Tell me about the exhibition.

The exhibition is called “Works 1978–2018.” It’s a wonderful exercise. I told [Peter Brant] he has a very specific view of what I make. He said, “I’m just looking for the best works.” I feel there is a relationship with all the works, but he will not admit that.

What is the relationship?

I think he is going after the more lyrical side of my work. I’m comfortable with that. I’ve gone to some darker places, but it’s not necessary to show every page of your life, even in a retrospective. It’s nice to show some pages that make sense together.

I work best on commission. I work best when the situation is the opposite of when someone says “Do whatever you want.” I’m not a fan of that situation. I don’t want. My job is not to want. My job is to be, so it’s a good situation when I can bounce back to other people’s minds, and listen to other people’s thoughts. I love to be proved wrong.

What are the pieces that Peter chose?

The exhibition space is a very specific space. Each of the rooms has a very unique character. There is a room that is very domesticated and luxurious with stucco and a chandelier that will have the portraits.

Then there is a small room filled with work that I am very fond of called The Pondicherry Pastels from my very first exhibition in New York. It’s very, very tactile and intimate. Tiny, tiny works.

The room full of light will have what you call in New York the “big time” paintings. There is a wonderful narrative of constructing and undoing and lifting and plunging. There is a broken heart, and a heart that is being cut away.

Then there is the room that is like a well that you can look down at from a balcony above. There is a tent there. The tent was made in Rajasthan. It showed in MASS MoCA. And two or three huge frescoes. There are two enormous watercolors that I made in 2011 called History of the Heart. But the keys to everything are the frescoes. I paint in clean layers. I paint without going back. There’s a beautiful Charlie Parker quote. He says, “Play the pretty notes and play it clean.”

My two favorite quotes about painting come from the music world. The other one is by Martin Feldman: “When a composer hesitates, he becomes immortal.” So, for me, the hesitation is key. Waiting is everything, of course.

What other works are included in the exhibition?

There is a so-called video room that I am using for the books. I prefer to read than to watch. And then there is a room filled with all the collaborations [with] the poets. Allen Ginsberg, Vincent Katz, Rene Ricard, and some paintings inspired by Indian text that will relate to the work. The letters are the seed that leads to the generation of the idea. The letters also inhabit parts of your body. It’s all from the classic texts of the family of traditions.

I studied Sanskrit.

It’s so beautiful.

Sanskrit is a kind of language where your posture counts. If you want to pronounce it properly, you have to sit straight. You can’t slouch. In India, the senses are not a bad thing. They are a gate to higher knowledge where you eventually bypass all the senses.

Are a lot of your friends still in New York?

I don’t want to be quoted, but most of my friends are dead.

I don’t know how we all found each other in New York back then. No one had phones. You just went out and ran into interesting people.

It’s because back then there was no one else in this neighborhood. It was empty and very beautiful. Alba and I always talk about this one night when we were walking in the Lower East Side with our little children and we were like “See? See how beautiful New York is?” and we were standing in front of a burned-out building. This is what we thought was beautiful then.

All that destruction felt honest.

Remember what the great Stendhal — who has gone out of fashion but remains a great writer — says, “Is it possible to make great art in a city that is not dangerous?” I’m just quoting Stendhal.

There was more magic in New York when it wasn’t so crowded. Life was like a treasure hunt before smartphones and the internet.

You can definitely not meet someone special if you are not looking up. But, I’m not taking a side on this question of New York. New York is still a knowledgeable city. Though, my favorite part of the internet is that now if you can’t remember the words to a poem, you can look it up.

Tell me about making the Hanuman Books.

I am most proud of a pirate edition of the Jack Kerouac book because you can’t get any permission to publish anything by Kerouac. And we just did it. I say we because it was me and Raymond Foye. We published [Willem] de Kooning’s collected writings — I don’t think there is anyone else who published this. They are just brilliant and wonderful writings. We went and asked Elaine [de Kooning, the artist’s widow], and she gave us permission to publish his writings. And then we published a number of the Beat poets who were all close to Raymond and who were my heroes when I was growing up in Italy. And we published relatively obscure writers from the 1930s from Europe, mystical, sectical writers on the modernist scene but marginal in certain ways, like Picabia, Jean Genet, and Simone Weil. And then we’ve published Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Robert Creeley, and Rene Ricard. I’m very proud of these books.

This is the universe I love to inhabit. I’m not a poet. I’m a painter, but I love the stance of the poet. I also love the fact that the poet only speaks if he has something to say. Otherwise, he just doesn’t say anything. I just love that. It’s very hard not to speak.

Most of all, Ginsberg and Kerouac, these poets had a strong relation to the East and everything that has been important to me. And they were also reflective of my America. When I thought of America when I was growing up, I thought of them. I was a little surprised to encounter the other reality. The other America.

Once you got here, it wasn’t what you thought it would be?

No. You think America is a very exotic place if you don’t live here. You have to live here a long time before it becomes penetrable. It seems so accessible but it really isn’t accessible. I don’t think it’s accessible at all. I still believe in the America I loved as a teenager. I still believe in Emerson, Thoreau, Ginsberg, and all the rebels and mystics.

America is a mystical place. It may sound paradoxical, but it is a mystical place. The land is a mystical place. If you start walking from New York and go west, the land is so soulful. So everything will be okay.

Did you take a lot of road trips?

I used to. Texas is so beautiful. I love Texas. I drove from San Francisco to Las Vegas. I drove from New York to New Mexico. From L.A. to New York. From Taos to New Orleans. My assistant was arrested once for having a spliff in Indiana. I had to go find a bail bondsman. But I won’t be quoted saying bad things about Middle America. It is a land full of spirit and mysterious things.

In Europe, you are always driving north and south. For someone who grew up in Europe, driving east to west is so special because the sun is in your eyes. It’s a very different experience of light than you get in Europe.

You grew up in Naples. Not so long ago, a very dangerous city.

Very dangerous. But Italy was a great place to see American artists when I was growing up. I saw Cy Twombly’s work when I was very young. It had a huge impact on me. It was related to antiquity, and he was turning around the equation. For me, antiquity was such a weight, but for him it was a pair of wings. That was an amazing lesson to learn that there were ways to embrace the past so it didn’t weigh you down. He is a marvelous artist. He is still up there for me.

A lot of artists were exhibiting in Italy before their time here. I saw a Richard Serra exhibition before Richard Serra became Richard Serra. When he was still making a very funky neo-Dada kind of work, which I think he rejects today, but it had a big impact on the artists in Rome in the late ’60s and ’70s. There were such legendary moments. Rauschenberg showed there in Italy and got a negative review. My gallerist, Sperone, brought to Europe paintings by Jasper Johns and Warhol in 1962. I got to see all that. We had a very up-to-date confrontation with America. It was inspiring. It was a golden age of American art.