A handful of forgotten early works by Anne Sexton, in which the American confessional poet explores a brighter array of subjects than her usual darker fare, has been uncovered by scholars and will see the light of day for the first time in more than half a century.

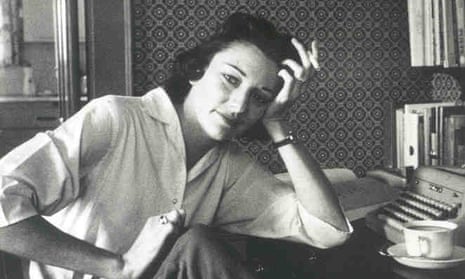

Sexton, known for her Pulitzer prize-winning poetry about mental illness and death, began writing after she was admitted to a psychiatric hospital following a breakdown. One of the US’s most acclaimed poets, she killed herself at the age of 45 in 1974, leaving behind her collections including her 1960 debut To Bedlam and Part Way Back and 1967’s Live or Die, which won the Pulitzer.

The lost work – four poems and an essay – was written in the late 1950s. In the poem Winter Colony, Sexton writes about skiing, of how: “We ride the sky down, / our voices falling back behind us, / unraveling like smooth threads.” In These Three Kings, she addresses fellow poet Louis Simpson’s admonition that “like ceremony and dance, praise should be forbidden to poets of this generation”, repeating the three words as she writes about a family Christmas. And in the essay Feeling the Grass, Sexton considers her husband’s gardening aspirations: “If I understood men, I would understand their need for a perfect lawn. We live in a square house on an average street in the suburbs, where the lawn is a very important thing.”

All five pieces appeared in the Christian Science Monitor between July 1958 and July 1959, which is where Zachary Turpin, assistant professor of American literature at the University of Idaho, discovered them while searching Sexton’s digital archive. Turpin, who has previously uncovered lost writings by Walt Whitman, worked with Erin Singer, assistant professor of English at Louisiana Tech, to look for any mention of the works.

“I remember early in our search, we were in the special collections library with a stack of Sexton’s work divided between us,” said Singer. “With every book that we moved to the ‘no, it’s not here’ stack, the more convinced I was that we had found something that was lost to us as a reading public. It was tremendously exciting.”

“It didn’t seem very likely that unknown Sexton poetry would simply be sitting there in the Christian Science Monitor, in all but plain view,” said Turpin, describing the poems as “not buried treasure so much as precious metals sitting right there on the surface, the slightest bit dusty, waiting for someone to kick one over and see the shimmer and the colour of it”.

“What makes these early poems so special is that one can see how commanding and experimental Sexton was, even during her first or second year as a publishing poet,” he said. “Yet there is also the sense that here is a real, complex person behind the words, a brilliantly associative crafter of words who is honing her art sharper and sharper, working for it, at the anvil – rather than magically emerging fully formed, some mythological creature without a speck of dirt on her.”

When they found no record of the works, they contacted Sexton’s eldest daughter Linda Gray Sexton, a memoirist and novelist who became her mother’s literary executor at the age of 21.

Gray Sexton said they offered readers an opportunity to see the growth of a well-respected and popular poet. “The reader can see where my mother came from. Then, rereading the last poetry she wrote takes on an entirely new meaning,” she told the Guardian. “They seemed of interest to anyone who either studied, or read, or loved Anne Sexton’s work. Here was her start.”

The poems and the essay are now being reprinted for by Fugue, a literary journal at the University of Idaho. In an introduction, Gray Sexton describes the works as “worthy enough for the world to see: the efforts of a very young poet trying her hand at the genre, making her own mistakes, but showing early definitive talent”.

Turpin and Singer say it is puzzling that the work has not previously been collected. “Our only guess is that they somehow did not fit the arrangement, the ‘sort-of story’ of Sexton’s first book,” they write in Fugue. “Broadly, they flesh out the arc of Sexton’s early career, breaking ground that her later poems would seed, nurture, harvest, and burn, and finally sow with salt. These pieces are footprints.”

Gray Sexton said the poems show how much work Sexton put into her craft. “As her daughter, these poems – such early efforts – reinforce the value of immensely hard and persistent work. She taught me that in order to grow within your genre, you must persevere, draft after draft. She believed that there was nothing to be ashamed of in looking back on what you’ve done and finding it wanting.”