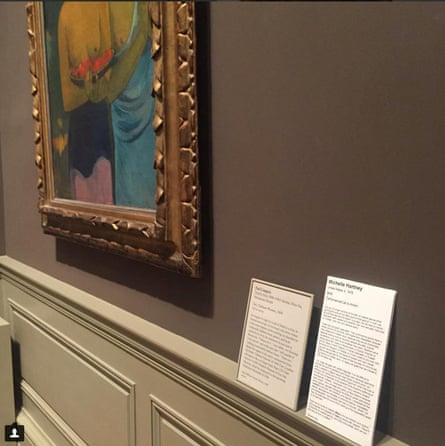

Earlier this month, Chicago artist Michelle Hartney walked into the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and placed her own wall label directly beside Paul Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women from 1899 – without asking for permission.

It’s part of Hartney’s own artwork Correct Art History, where the artist leaves wall labels to call out sexist, misogynist and abusive artists when museums will not. Her project includes calling out Pablo Picasso (who called women machines for suffering), Balthus (who sexualized prepubescent girls) and Gauguin (a pedophile who had three child brides in Tahiti).

Her placard reads: “We can no longer worship at the alter of creative genius while ignoring the price all to often paid for that genius,” quoting Roxane Gay. “In truth, we should have learned this lesson long ago, but we have a cultural fascination with creative and powerful men who are also ‘mercurial’ or ‘volatile’, with men who behave badly.”

While museum wall labels were once used to explain the “title, artist, date” status of an artwork, they’re quickly becoming a place to spark debate, rewrite history and acknowledge untold stories. In light of the #MeToo movement, wall labels are finally starting to include the controversial information that surrounds an artwork or artist. It could soon become the expectation.

“Providing biographical information about artists on wall labels is a common practice with museums, but when it comes to sexual violence, gross sexism or racism, the museums, curators and critics are often choosing to eliminate this information,” said Hartney. “It results in them taking control of the narrative surrounding male artists, such as Picasso, Gauguin, Chuck Close and many others.”

But getting rid of controversial artworks, often works that protesters demand be taken down, is not the answer, says Hartney. “We need these works of art to remain in museums so we can learn from them,” she said. “Educating and presenting the truth is how we learn and do better; this information would be a powerful educational moment because it will show how long the patriarchy has ruled over women.”

Just as confederate monuments from the south have been taken down this year, as well as the statue of controversial gynecologist J Marion Sims from Central Park, adding a plaque offering historical context is not enough. Wall labels need to be updated in a different way to look back on art history that reflects the present.

The Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts has added wall labels to portraits of figures with ties to slavery, wealthy patrons like John Freake, painted by American artists Gilbert Stuart and John Singleton Copley. A wall label in the American wing reads: “These paintings depict the sitters as they wish to be seen – their best selves – rather than simply recording appearance. Yet, a great deal of information is effaced in these works, including the sitters’ reliance on chattel slavery, often referred to as America’s ‘peculiar institution’. Many of the people represented here derived wealth and social status from this system of violence and oppression, which was legal in Massachusetts until 1783 and in regions of the United States until 1865.”

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston added a wall label this year to address Austrian artist Egon Schiele, who faced criminal charges for showing erotic drawings to a child (his charges of kidnapping and raping a 13-year-old girl in 1912 were dropped in court). The wall label was updated to read: “Recently, Schiele has been mentioned in the context of sexual misconduct by artists, of the present and the past. This stems in part from specific charges (ultimately dropped as unfounded) of kidnapping and molestation.” It also notes that Schiele “has long had a reputation as a transgressive at society’s edges”.

Earlier this year, the Whitney Museum of American Art came under fire for showing Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old black boy who was accused of flirting with a white woman in 1955, and was lynched. Schutz’s painting of Till’s open casket showed at the Whitney Biennial, causing an uproar from protesters. The curators kept the painting up but acknowledged the complaints in an updated wall label that read, in part: “This painting has been at the center of a heated debate around questions of cultural appropriation, the ethics of representation, the political efficacy of painting and the possibilities or limitations of empathy.”

As a partial solution, feminist art collective, the Guerrilla Girls, recently designed a poster entitled 3 ways to write a museum wall label when the artist is a sexual predator, which uses Close, the artist accused of sexual misconduct, to show a three-tier option of portraying the artist and his accusations. The lowest-ranking wall label is for museums afraid of alienating billionaire trustees and collectors, the middle category is for museums conflicted about disclosing an artist’s abuse, and the longest, strongest wall label is for museums who need help from the art collective, where the placard reads: “The art world tolerates abuse because it believes art is above it all, and rules don’t always apply to ‘genius’ white male artists. WRONG!”

But what surprises the Guerrilla Girls is they have not seen museum wall labels change much in light of several artist’s sexual assault or misconduct accusations. “Every museum is deliberating right now about how to respond to the #MeToo movement,” said a representative from the group. “No museums have put up our wall labels, but some will have the guts to exhibit our poster, so in a way, they will be putting up that label.”

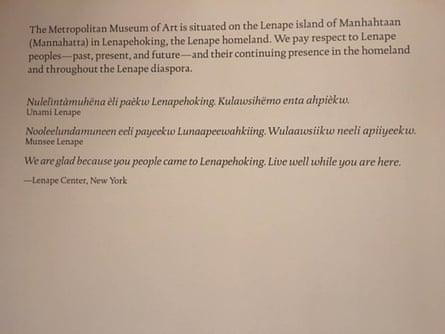

Curators are making progress in some museums, like the Met’s American wing curator Sylvia Yount, who recently opened an exhibit on Native American art. The wall label at the beginning of the exhibit is a land acknowledgment, which reads: “The Metropolitan Museum of Art is situated in Lenapehoking, the homeland of Lenape peoples, and respectfully acknowledges their ongoing cultural and spiritual connections to the area.”

“We felt it was critical to add the land acknowledgement – as well as the longer welcome with the Native language greeting – in order to honor the original inhabitants of the land on which the Met sits, a first for us,” said Yount. “We also invited representatives of the Lenape Center of New York to deliver a public blessing at the opening reception, underlining the importance of the community’s past, present, and future in the New York area, in particular. Both are tangible evidence of the American wing’s commitment to building long-term relationships with a broad range of tribal communities, especially those in our own backyard.”

As for Hartney’s own performances, they are fueled by looking at institutions and their own codes of conduct, as well as their mission statements, such as the Art Institute of Chicago, which is said to “collect, preserve and interpret works of art of the highest quality”.

“In my opinion, the institution is not acting in accordance with their ‘profession’s highest ethical standards and practices’ when they knowingly eliminate negative narratives from an artist’s legacy,” said Hartney, “often using the excuse that it distracts from the art and can change a viewer’s experience with the art.”

Some museum directors are listening, however. To Diane Peabody Straw, the executive director of the Women’s Museum of California, this kind of criticism is at the forefront of their programming.

“When your organization has a code of conduct and a mission statement, it does a public good to acknowledge the artists you choose to place in your gallery that do not live up to those principles,” she said. “It allows us as a community to discuss the significance of the art and how it fits into the narrative of the exhibit while ensuring that victims of sexual violence feel safe and heard.”