French street artist Invader heads ‘into the white cube’ for a solo show — and into the streets for a new L.A. ‘invasion’

“Hallo!” A slender Frenchman in cargo pants and a hoodie pops around a corner, sprightly, at Over the Influence gallery, waving his palm in a quick half circle. He wears a black baseball cap, giant, mirrored ski goggles and a cotton neck warmer pulled up to his chin, so that only his cheeks and mouth are exposed.

Suddenly he lurches forward, sticking a red and white alien pin to my shirt.

“You’ve been invaded!” he says, laughing heartily, before quickly yanking up the neck warmer, which had slipped down for a second.

This is the anonymous French street artist “Invader,” known globally for his mosaic tile works, featuring pixelated versions of the Space Invader video game character, that he illicitly puts up on building facades from Paris to Perth, Hong Kong to Kathmandu. He’s visiting from Paris for his solo exhibition, “Into the White Cube,” which includes his first ever publicly displayed canvas works. They’re being installed now at the downtown Arts District gallery.

Later Invader will change into an over-the-head, Salvador Dali mask in which everything above the neck is encased in rubber but for his pupils peeking through eyeholes. But that costume muffles his speech. So for now, this more relaxed disguise allows him to chat – though it’s a bit like a toddler playing Peekaboo who covers his face thinking no one in the room can see him. Invader is clearly tall and slim, nearing 50, with thin lips and narrow cheeks that are peppered with graying stubble. He has clean, manicured nails. Tufts of dark and silvery hair creep out from under his cap. He smells of a freshly-finished cigarette.

RELATED: Test your street art IQ: Invader lands in L.A. Can you find him? »

Invader settles into a folding chair facing his paintings on the wall, deceptively simple brush renderings of his pixelated video game imagery or cellphone emojis in peppy, candy-like colors. He’s surprisingly guileless, though also serious, about his work. The paintings are “still lifes,” the street art is a “mission.”

“I just want to put something in the landscape that people can smile about it,” he says. “It’s something positive. My goal is to produce art for everybody in the city and create some beautiful things.”

A prolific artist with a rabid fan base, Invader has been populating the streets with his mosaics for 20 years, coming of age in the late 1990s with the rise in popularity (and ensuing commercialization) of street art itself. If street art were a high school, Invader’s peer group would include famed artists Banksy and Shepard Fairey, both friends, he says. His street art practice dovetailed with the advent of the internet and social media, which not only shaped his pixelated aesthetic but informed — and spread — his underlying message about the prevalence of digital culture.

When he arrives in a city, Invader surreptitiously plasters it with artworks – an “invasion,” he calls it. He’s invaded 77 cities on five continents, putting up more than 3,500 public works to date; in May he visited L.A. for the ninth time, blasting the city with 29 new pieces. About half of the 200 works he’s installed in L.A. over the years are still up. He obsessively chronicles his work in photographs, online maps and books he calls “invasion guides.” Four years ago, Invader debuted a Smartphone app allowing fans to snap pictures of his mosaics hiding in plain sight and, if they’re authentically his, rack up points in a sort of international “Where’s Waldo” meets “Pokémon Go” mobile game.

“It’s to be playful, have a dialogue,” he says.

Finding the perfect location — “adapting the mosaic to the culture of the city” — is a precise process he calls “urban acupuncture.” A tile depiction of The Dude from the film “The Big Lebowski” on an exterior wall of a Koreatown bowling alley is perfection, he says. He might spend six months planning an invasion, which includes designing graphics, sometimes pre-assembling patches of tiles if it’s a large or complicated piece, and studying Google Street View to hone in on potential locations. He doesn’t interact with local graffiti or street art crews in cities he visits; instead, he works with a local “accomplice,” who photo-documents spaces he aims to invade beforehand so he can whittle down locations and plan logistics. Then that person helps him lug buckets of cement and boxes of tiles into difficult or remote spaces.

His cousin, Thierry Guetta, a.k.a. the French-born, L.A. street artist Mr. Brainwash, has helped him with projects here. Once, he contacted a fan on Instagram to help him execute a Tokyo invasion. He’s been arrested countless times in multiple countries, but never charged, he says.

Often Invader works at night. If in daylight, he might dress as someone indigenous to the environment, like a construction worker in a crowded urban area. He posed as a hiker when on Dec. 31, 1999, he famously invaded the letter “D” in the Hollywood sign. (He’s since invaded every letter in multiple visits.) His own parents in France think he works as a bathroom tiler.

RELATED: How I discovered I was living with an alien ‘Invader’ »

“I don’t tell them because I think they will speak to all of their friends and the mystery won’t last,” he says.

He tugs at the neck warmer. Anonymity is a drag. So why bother?

“First it was for security. Then it became a way of life,” he says. “It’s interesting. I can go to my own openings and listen to what people are saying. It’s like being a spy.”

Invader won’t reveal much about his personal life but says he grew up in Paris, in a “medium-sized,” middle-class family. His parents weren’t artists, but filled the house with art. He studied liberal arts at university and art afterward at the École des Beaux-Arts, but floundered in his early 20s, with no idea how to become a professional artist.

“It’s very hard when you’re a young artist to go into a gallery and nobody cares about you … they can be very snobbish.”

He built websites for small businesses to earn money while making art at home — paintings and “experimental stuff.” The web work sparked an interest in digital imagery and pixelization. He’d played Space Invaders as a kid and the cheeky alien image lent itself to his aesthetic. He had trouble painting pixels, however, so switched to working with small bathroom tiles. One day in 1998, on a lark, he hung one of his alien mosaics outside on a cement wall. “So more people could see it.”

A few months later, he had an artistic awakening: “I realized ‘Invader’ meant also ‘invade space,’” he says. “There was a concept.” Suddenly everything made sense. He channeled his frustration over art world exclusivity into spreading free art in the streets. Within six months, he’d put up more than 100 works in Paris, then ventured to London on a train with a suitcase full of tiles. He built a website and burgeoning fans, along with curious journalists, came calling.

Invader disappears for a minute, then returns wearing the Salvador Dali mask, a quizzical expression frozen across its face. He tilts his head to the side, mock-twirling the ends of his fake handlebar mustache.

Chronicling his work in the streets is as important as the finished artwork, he says. The photographs that live on after the more ephemeral street art is destroyed or removed are about capturing a moment in time — they’re “time capsules,” he says. The neighborhoods in the pictures will inevitably morph, fashions and hairstyles will change, businesses will close and new ones will debut; but the tiny artwork may remain for decades, a timeless mosaic marker, a witness of sorts, that also, ironically, itself represents a cultural moment in time: 1970s and ’80s video game culture.

“This is a Suykhcht,” he says of one photo on the wall.

“A what?”

“A Suykhcht,” he repeats emphatically.

It’s all a breathy, mumbled mess under the rubber mask.

Invader whips around, pulls the hoodie over his body for cover, swaps masks, then whips back around, now wearing the ski goggles, his mouth unobscured.

“A souk,” he says of a photograph depicting an Arab market in Kathmandu, Nepal, where an Invader mosaic hangs above woven carpets for sale.

Despite the playfulness, there are more complex undertones to Invader’s work, touching on authenticity, replication and the art market.

He encourages fans who can’t afford to buy his work to make copies, selling limited editions of “Invasion Kits” on his website so they can assemble the tiles themselves. In a relatively new phenomenon, fans have been replacing famous works that have disappeared from the streets — “reactivations,” they’re called. Because Invader’s work is unsigned and unauthenticated, it’s impossible to prove what’s his and what’s a copy, making the sale of stolen works at auctions or on EBay more difficult.

He also makes one “alias” mosaic — meant to be sold in a gallery – for every work he puts in the street. It’s better quality than the street art version, built to last – but it’s decidedly the copy, not the original. Each alias comes with an ID card recording the date and location of the original invasion. The collector, as Invader sees it, is symbolically inked to or “owns” the accompanying street art work, even after it’s gone, complicit in the illegal invasion.

Invader has shown his work in museums and galleries around the world. But “Into the White Cube,” a career survey on view through Dec. 23, marks a moment in which he’s coming full circle since he started off as a painter. “20 years later I come back to the canvas because I like to experiment with mediums,” he says, “and also because as an artist, painting is the holy grail.”

The exhibition’s title, he says, poses the obvious question: How do you bring a street artist into a gallery?

“It’s not easy to be good in both [places]. But it’s not a paradox,” he says. “I’m an invader, I’m a street artist; but I’m also an artist.”

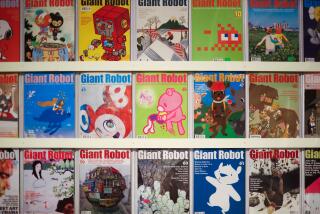

The work in the show is bright, pop cultural and irreverent. There are enormous, resin pin buttons featuring phrases like “Humans Suck!”; there are auction catalog tear-sheets scribbled with black marker; there’s a version of David Hockney’s 1967 painting “A Bigger Splash” made from Rubik’s Cubes. One wall features his latest invasion guidebook, “Los Angeles 2.1,” each with a hand-tiled, mosaic cover. Another wall is a colorful smash-up of individual mosaic works, tiny and ginormous.

That his alias works range from $20,000 to $300,000 is something Invader admits is “a bit strange,” he says. But he also feels lucky to be making a living from his art. “It’s a dream of every artist. I’m thankful and happy about that.”

Meantime, his street works are far more prevalent and democratic, he says. “Anybody can enjoy my work in the street, from the president to homeless people. My art has more visitors in the subways of New York than the Louvre.”

Lest things get too serious, just ask Invader why the Dali mask?

“Because he was a brilliant “arteeest,” he says.

Does Invader like Dali’s work?

“No,” he says flatly. “But I love the mustache.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.