Seventy-five dancers are to perform a total of 300 solos created by Merce Cunningham in an event staged in three cities to mark the trailblazing choreographer’s centenary. Three performances will take place within a 24-hour period in London, New York and Los Angeles; each will have a group of 25 dancers performing 100 solos from Cunningham’s vast body of work.

At the Barbican, in London, the lineup of participants come from a striking breadth of dance backgrounds. They include Royal Ballet principals Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball; Michael Nunn and Billy Trevitt, co-founders of the all-male BalletBoyz company; choreographer-dancer Siobhan Davies, who was a friend of Cunningham’s; Thomasin Gülgeç and Mbulelo Ndabeni who have both previously performed Cunningham’s work for Rambert; and Toke Broni Strandby from Candoco, which comprises disabled and non-disabled dancers and who recently performed on the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing.

Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event will take place on what would have been Cunningham’s 100th birthday, 16 April 2019. The three productions, each lasting 75 minutes, will be live-streamed, which means audiences around the world can see the Barbican performance, followed by one a few hours later at Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, and finally one at UCLA’s Centre for the Art of Performance in Los Angeles.

The event has been curated by former dancers in Cunningham’s company including Daniel Squire, who has organised the Barbican event. The earliest of the solos comes from 1953 and the latest from 2009, the year of the choreographer’s death at the age of 90. Sometimes several solos will be performed concurrently. “They won’t all be presented as solos in terms of a dancer alone on stage,” says Squire. “It’s really about re-contextualising a lot of the material.” The organisers have defined a solo as any time, in one of Cunningham’s pieces, when a dancer is the only one performing a particular sequence alone, no matter how many other dancers share the stage.

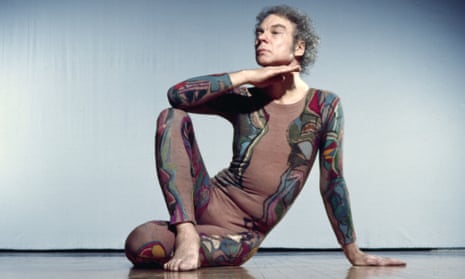

American dancer Beatriz Stix-Brunell, a first soloist of the Royal Ballet, hasn’t danced Cunningham’s work before. “I will be discovering as I go along,” she says. Stix-Brunell will perform four solos at the Barbican including one of the longest, Changeling, which dates from 1956 and which Cunningham created as a solo for himself. Stix-Brunell says she fell in love with Cunningham’s work after seeing Summerspace performed at the Juilliard school in New York. “We’re learning the solos independently of each other,” she explained. I think it will be cool for us to see everybody coming together from such different companies. As a dancer, that’s always fuel for you … We all come from different backgrounds but we’re all inhabiting this one style.”

For the Barbican production, the 25 dancers range in age from early 20s to late 60s. A collage of black and white images created by Richard Hamilton will be projected across the back of the stage; the collage, entitled Shadows Cast by Readymades, was used for a Cunningham performance at the Barbican in 2005. The performances in the US will each feature different set designs. There will be separate musical scores for each of the three events, with the music conceived independently of the dancing, which was one of Cunningham’s preferred methods. “These two separate arts exist in time and space,” explains Stix-Brunell, “but it’s kind of free. One doesn’t rely on the other.”

Co-ordinating the rehearsal and performance schedules of the 25 dancers has been a logistical challenge for Squire, who was a member of Cunningham’s company from 1998 to 2009. “My experience of the Cunningham studio was that everyone who came there and took classes or danced in the company drew from lots of different people’s take on the work. Often, on a staging project, there will be one artistic voice in the room trying to bring all of that together. The experience for the dancers is that they’re receiving instructions from one person. One of my main concerns is that for all 25 dancers they would have at least two, if not three or four, people that they’re learning from.”

Despite the considerable challenges involved in co-ordinating the performance, Squire is thrilled at the prospect: “When I first saw the cast list I thought gosh we could just have those 25 people stand on stage and it will be riveting. Add to that the fact that they are going to do Merce’s work and it will hopefully be a wonderful experience.”

Stix-Brunell says that Cunningham’s choreography includes “unpredictable changes in speed and direction and rhythm” and, in a change from the Royal Ballet, “it’s barefoot. We don’t dance barefoot very often so that will be a whole different feeling.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion