Introducing The Atlantic Crossword

We made a cozy new corner of the internet for smart people who like words.

The miracle and menace of each era is original, but the debate over how Americans spend their time remains extraordinarily consistent over the decades.

Today, the smartphone is the attention portal that stirs the most awe and anxiety. A century ago, the crossword puzzle occupied this cultural space.

The first crosswords appeared in newspapers during the Woodrow Wilson presidency, in the years leading up to World War I. Panic began, as it often does, among those who derived deeper meaning from the fad’s furious popularity—the people who saw it as evidence of more dramatic changes under way. (See also: the fidget spinner. And, for that matter, the telegraph.)

To be fair, things did get a little hectic. Trains began stocking their observation cars with dictionaries. Fights broke out at the reference desks of libraries across the country. Doctors warned of the dreaded “crossword-puzzle headache.” At Princeton and Mount Holyoke, professors argued about bringing puzzles into their curricula. Puzzles were banned in courthouses, where distracted public officials played on the job. Pastors gave their congregations puzzles that contained words from their sermons. Peter Mark Roget, famous for his thesaurus, was declared “the saint of crosswordia.” Puzzles were stitched into the hems of dresses and stamped onto Parisian hosiery—a trend popular only among the American women who imported them; French women reportedly found the stockings “hideous.” People used puzzles to announce their engagement. Newspapers reported an uptick of women divorcing puzzle-obsessed husbands. In at least one case, detectives called upon crossword champions to help investigate a man’s death.

All of this was evidence of “an age of restless intellectualism,” writers argued. Columnists coined words such as crossworditis. People worried that puzzles would replace literature, that the utility of three-letter words—gnu! emu! eel!—would rewire people’s brains. Word games were derided as childish, even as a form of madness. “There is a taste for raw meat,” the legendary ad man George Burton Hotchkiss said in 1924. “Plain speaking has become fashionable. Entertainment is sought more widely than instruction, possibly because information is too cheap.”

To which a nation mostly shrugged and said: Lighten up, already.

The New York Times took nearly two decades more, until the start of World War II, to print its own puzzle, which it finally introduced after the attack on Pearl Harbor, as a diversion for a deeply worried readership. (“We ought to proceed with the puzzle, especially in view of the fact it is possible there will now be bleak blackout hours—or if not that, then certainly a need for relaxation of some kind or other,” the paper’s Sunday editor wrote in a memo to the publisher at the time.)

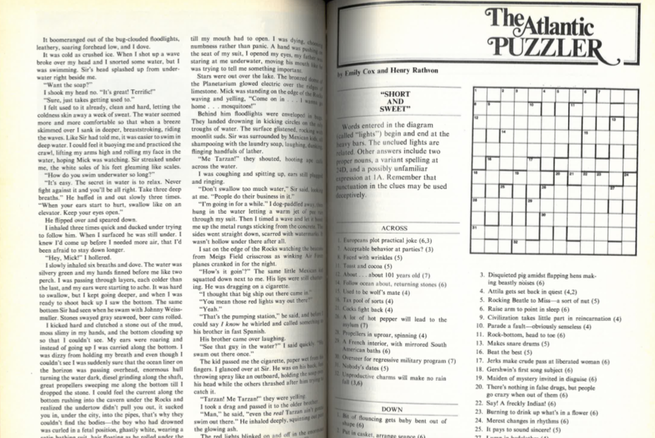

Not until September 1977 did The Atlantic launch its own beloved crossword puzzle, The Atlantic Puzzler, created by a couple now known as puzzle-making royalty, Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon. The duo also ran a biweekly word game for The Atlantic on America Online beginning in March 1995. The Puzzler ended its run in print in 2006, but was briefly revived online. (Its fans complained “loudly and sometimes in Latin” about this move, according to a report at the time.)

Today, at a moment when entertainment and information are again so curiously intertwined, when the pace of the news cycle is punishing and the information ecosystem itself is profoundly chaotic, The Atlantic is again creating a cozy and reliable space for crossword puzzles. The Atlantic Crossword is a mini puzzle, constructed with the smartphone player in mind, that gets a little bigger and a little more challenging each weekday. (You can also play your way through our archive of past puzzles.)

Caleb Madison, our talented puzzle creator, is carrying on a tradition first established by The Atlantic’s founders in 1857, when they promised to care for their readership’s “healthy appetite of the mind for entertainment in its various forms.” The Atlantic is a place for news, reported analysis, criticism, investigations, and commentary, yes, but also a place for humor, wit, and delight.

I hope you’ll enjoy this new puzzle with all the enthusiasm (and none of the violence) of the crossword craze of 1924—or at least consider the position articulated by the woman who wrote this to her local newspaper that year: “In this day of looking and listening—of movies and radio—a sport which demands a little thinking should not be utterly despised.”