At first, it sounds like an obscure cinephile joke. At a time when new movies are released on streaming services and film-makers are begging audiences to watch their new blockbusters at the cinema rather than on smartphones, the BFI plans to show some of its earliest footage on the biggest screen possible. The archive gala for this year’s London film festival will present a selection of Victorian films on an Imax, with a lecturer and live band, as they were originally shown. What was a novelty then may well retain some of the shock of the new 120 years later.

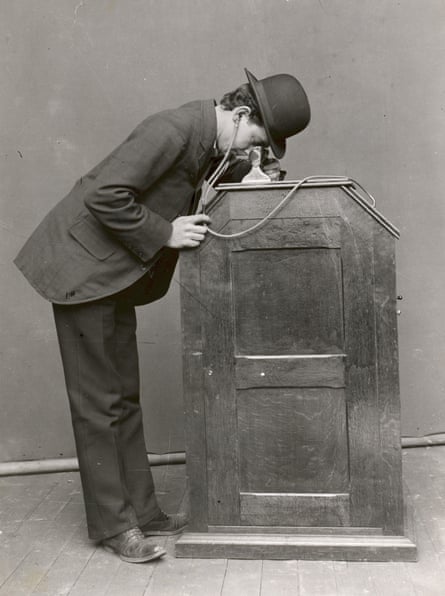

These are no ordinary 19th-century films, if there is such a thing. They are large-format movies, shot on 60mm or 68mm film, so each frame is around four times the size of traditional 35mm. The man responsible for the 68mm images is William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson, a British inventor born in France, who worked at Thomas Edison’s New Jersey laboratory in the 1880s. “He was the guy who invented the movies for Thomas Edison,” says Bryony Dixon, curator of silent film at the BFI. “He basically invented a film strip that went through a kind of cabinet on a loop and you would look at it through an eyepiece. A bit like a VR headset today.” That cabinet, first shown to the public in 1893, was called a Kinetoscope. Although it showed moving images, they could only be viewed by one person at a time. These single-user nickel-in-the-slot machines were a novelty, but an unprofitable one, and Dickson left Edison’s company in search of bigger things. He founded the Biograph Company, where he made 68mm films that could be projected in front of audiences. In 1897, he returned to Britain to start shooting.

“Dickson filmed all sorts of things. He was very well connected,” says Dixon. “So he starts off with Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. Unluckily none of those films of his survive, but he is invited to go to Clarence House by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII. He films all the royals in the garden, rather posed around a tea table with a parrot, a dog and a small child.” Wherever a newsworthy event took place, Dickson brought his camera: the Henley Regatta, the Boat Race, Herbert Beerbohm Tree performing King John. He worked fast, too. That diamond jubilee footage was screening in the US a week or so later. When he covered the Grand National, he shot the race in the afternoon and developed the film on the train back to London. He had it processed back in the capital, and screened it in the West End at 11pm.

Dickson went to Italy where he captured beautiful scenes of Venice and filmed the pope in the Vatican. His biggest coup was taking his camera to South Africa to shoot the Boer war. Although the camera was unwieldy, big enough to carry the reel of 68mm film and a motor, Dickson got close to the action. Among the films showing at the Imax are scenes of British troops repairing a bomb-damaged bridge and withdrawing from the Battle of Spion Kop across the Tugela River. This is the earliest surviving footage of a British war – and it’s quite remarkable to watch.

These films, most under a minute long, would have been shown by the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company at the Palace Theatre of Varieties in Cambridge Circus, built in 1891. The films would be projected on a large screen in between the live performances, advertised as “an act by itself and without rival”. The Palace was a higher class of music hall and ticket prices weren’t cheap. In fact, these large-format Biograph films were shown in an early flowering of respectability for the new medium – though once the cinema became part of fairground shows in the early 20th century, it lost its cachet. It is notable, Dixon explains, that when the Boer war films were shown in provincial halls, a more jingoistic atmosphere prevailed, with union jack bunting and patriotic cheers. At the Palace, the films were received as news footage rather than entertainment. As they were so brief and had no title cards, a lecturer would explain them to the crowd as they unspooled, accompanied by the house orchestra.

At the Imax screenings, the films will be shown at their maximum size and, crucially, newly restored at 4K from the nitrate originals, which were scanned at 8K. It was only recently that the technology became available to get the most out of these images. “There was an opportunity to upgrade these in particular because they’re so spectacularly beautiful,” explains Dixon. “So, working with a laboratory in the Netherlands called Haghefilm, we could scan them at much higher resolution and get pictures that you can really blow up big.”

The benefit of extracting all this detail and watching the films on such a giant screen is that they hardly look Victorian at all. “With nearly all of the people I’ve shown these films to there is an audible gasp when they see something from 120 years ago and they look new. That’s a very strange feeling,” says Dixon. “All of those things that tell you something is old have been stripped away.” These are films made before genres and cinematic conventions were established, before the idea of directors and stars. The images feel raw and immediate.

Not only that, the Victorians come to life in front of our eyes. “You can really hone in on little bits of human behaviour,” says Dixon, pointing out a beaming toddler feeding the pigeons in St Mark’s Square, or a gentleman placing his hand slyly on a young lady’s back to keep her steady on a boat at the Henley Regatta. “These are 20-year-olds behaving like 20-year-olds, just like they do now.” Seen in these remarkable films, everyone from British royalty to traders at a Venice vegetable market or iron foundry workers in Newcastle seem much more natural that they do in the posed photographs of the day.

One of the most charming films in the selection is shot on a beach in Worthing. In the foreground, a group of volunteers demonstrate some lifesaving first aid, although they accidentally move the “body” out of shot, and have to be coerced into dragging it back into the frame. You may not notice that awkward moment on first viewing, however, as the frame is filled with an distractingly well-composed shot of the sea front: waves lapping the beach, a crowd of onlookers and an impressive depth of field.

There’s so much to see in these films beyond what the camera is ostensibly pointing at. It’s a lost world made new again by the meeting of Victorian and 21st-century technology.

The Victorian Moving Picture Show screens at the BFI Imax on 18 October as part of the BFI London Film Festival, previewing a wider Victorian film digitisation project for 2019