In 1991 Max Klaar, a retired German lieutenant-colonel, presented the municipality of Potsdam with a replica of a famous carillon, which from 1797 to 1945 had played themes by Bach and Mozart (Papageno’s Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen from The Magic Flute) from the tower of the city’s Garrison church. Both the tower and bells had been wrecked in an air raid – the ruins finally being removed by the East German government in 1968. The carillon, paid for by private donors, was a step in the hoped-for reconstruction of the church.

How very charming, you might think, except that Klaar had an agenda: he was a Nazi apologist. If you look on the internet (but please don’t), you will find him, for example, endorsing the thoroughly debunked lie that General Eisenhower had a million German prisoners of war killed in death camps.

His choice of building was controversial: the church was the setting in 1933 of the famous handshake between Hitler and the venerated conservative general Paul von Hindenburg, which conferred the old establishment’s approval on the Führer and thereby cemented his grip on power.

Although Klaar withdrew from the rebuilding project in 2005, it continues without him. At one stage the Prince of Wales’s architectural summer school lent its support. Last year, work started on the church tower, with completion due in 2020. Protests against it continue, but supporters say that to leave the site empty would “give victory” both to the Nazis and the East German communist regime.

According to Stephan Trüby, a professor of architecture at the University of Stuttgart, the Garrison church plan is an example of what he claims is now a disturbing pattern. “We can currently witness a cultural tendency of using seemingly harmless terms like identity’, ‘tradition’ and ‘beauty’ to establish an idea of ethnic purity protected by a fortress Europe,” he says. Elsewhere, writers wield terms such as heimat (home) and boden (soil/earth), which have both a long tradition in German thought and specific far-right meanings.

An added attraction of many reconstruction projects, Trüby argues, is that the damage being repaired was inflicted by Allied bombing, which reinforces the far-right narrative that Nazi Germany was as much a victim as a perpetrator of war crimes. In a newspaper article earlier this year, Trüby pointed to both the Potsdam project and the “new Old Town” in Frankfurt, the reconstruction of part of the city centre that was formally inaugurated a week ago.

Since Trüby’s article, Sarah Manavis has written in the New Statesman about a related tendency, and one not confined to Germany – social media accounts that promote messages of white supremacy through the “seemingly wholesome” beauties of European architecture. “Everything is indirect,” says Trüby, “and that is the point. In contrast to the old right, the new right learned to speak in euphemisms, in disguise.” The hate that dare not speak its name, you could call it.

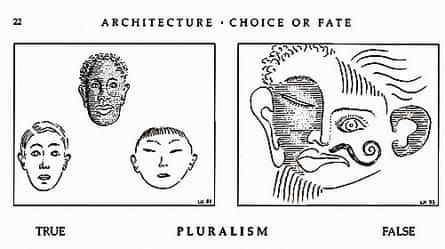

Trüby names Léon Krier – born in Luxembourg, and the master planner of Prince Charles’s traditionalist development of Poundbury in Dorset – among those associated with these endeavours. He points to a drawing of “pluralism” published in Krier’s 1998 book Architecture: Choice or Fate (which is dedicated “A mon prince”) and recently republished in the German magazine Cato. Above the label on “true” pluralism he shows three male faces – one white, one black and one east Asian, each separated from the other. Above “false” pluralism he shows a cubistic mashup of races. Trüby calls it “racist”; Krier says it is not.

Cato, claims Trüby, insidiously combines respectable conservatism with radical rightwing positions. It includes architecture and aesthetics among its topics, and articles by Krier and the British conservative philosopher Roger Scruton. Its editor, Andreas Lombard, has defended in print the late Rolf Peter Sieferle. Sieferle wrote, among other assertions in his book Finis Germania, that “the Jews’ guilt for the crucifixion of the messiah was never recognised by them. The Germans, who recognise their merciless guilt, have to disappear from the surface of real history.”

Another key figure is Claus Wolfschlag, a writer who has contributed to what Trüby calls “openly antisemitic papers” such as Zur Zeit, which once described Hitler as a “great social revolutionary” who was not to blame for the outbreak of the second world war. “Whoever wants to talk about the people and their homeland,” Wolfschlag once wrote in a far-right anthology, “can certainly not remain silent about architecture (in and with which the people ultimately live).” He favours monumental eruptions of masonry, such as the bombastic and cartoonish monument to the Battle of the Nations, built in Leipzig in 1913. He also likes the stone towers built across Germany and its empire to commemorate Otto von Bismarck, not to mention Ordensburg Vogelsang, a Nazi training centre draped over wooded hills in North Rhine-Westphalia.

His significance for present purposes is that the new Old Town in Frankfurt goes back to a motion he submitted to the city council in 2005, which, although at first voted down, proposed the reconstruction that has now come to pass. His ally was a local politician, Wolfgang Hübner, a man who recently celebrated the departure of the Muslim Mesut Özil from the German national football team as “a victory for all those forces in Germany who no longer bow to globalist profiteers and their media propagandists against denationalisation and uprooting”.

And so the new Old Town now stands, delivered to high standards of execution and accuracy: an uncanny simulacrum of buildings that stood there before the war, the haphazard growth of centuries replicated in one go. Some are half-timbered, some prettily gabled, some rendered and painted in soft shades of pink or blue. Its star attraction is the Haus zur Goldenen Waage (the “house of the golden scales”), whose bright decoration now glows as if a jerkined 17th-century craftsman had just this moment descended, paintbrush still wet, from his wooden ladder.

With the city’s glass banking towers looming in the background, the new Old Town seeks to counter Frankfurt’s enduring fear that it has no soul. It might now have a post-Brexit role in luring financiers from London. I believe its supporters, most of whom are not far right, when they say it’s popular with the general public and tourists. For Wolfschlag it “ends the cult of guilt” by “reclaiming historic built heritage”. For Trüby, the problem is not with reconstruction itself – in cases of catastrophe, as with the fires at the Glasgow School of Art, he believes it is desirable; he objects to the politics of Wolfschlag and Hübner.

Which brings us to an old issue in architecture – the extent to which it can be separated from the ideologies that shape it. It is a question familiar to Krier, who built part of his fame with a study of Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer. “To the question ‘Can a war criminal be a great artist?’”, he has said, “my answer is clearly yes”.

He is now a friend and supporter of both the Garrison church and the new Old Town projects. “I have read a number of articles by Wolfgang Hübner and one by Claus Wolfschlag,” Krier tells me, “which I found to be convergent with what I teach and practise. I found there no racist, fascist, Nazi statement.” He also reaffirms support that he has previously stated for the “formidable mind” of Ken Jebsen, a broadcaster fond of conspiracy theories that link Jews, America, global domination and secret support for the Nazi war effort.

Krier has consistently expressed his belief that traditional European urbanism allows “open modern society” to flourish. He invokes the support of the American Jewish architect Robert Stern as evidence that his liking for Speer is blameless. The message of his drawing of the three faces is, he says somewhat obscurely, “that mixing races still produces true traditional plurality, not modernist gobbledegook… If I was a racist I would state so openly and unambiguously.” He says that “the top figure [in the drawing] is a mixed-race person”. I can’t see that myself.

Krier himself may not be fascist. Nor are most of the people involved in reconstructing the Garrison church or the new Old Town. But the defence of the political neutrality of architecture is wearing thin. Why exactly, of all the treasures lost in the war, is it so important to rebuild this particular church? Why does it so happen that Wolfschlag’s favourite buildings are imperial or Nazi? Why is Speer so fascinating?

In these dangerous times, it’s important to show which side you are on, not to assist in the blurring of boundaries between the reasonable and the extreme.