The Difficulty—and Importance—of Talking About Young Dead Celebrities

Two recent hip-hop controversies show how hard it can be to discuss substance abuse and other fatal trends without offending.

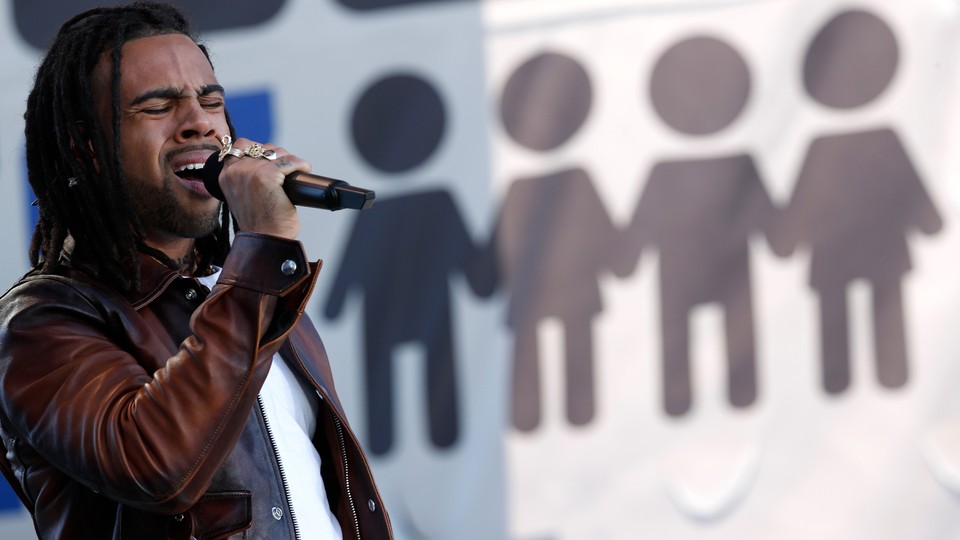

The Latin phrase de mortuis nil nisi bonum—“Of the dead, [say] nothing but good”—dates back thousands of years. But it echoed loudly across the hip-hop world last week. In a freestyle at the BET Hip-Hop Awards, the Chicago firebrand Vic Mensa was widely heard as dissing the late rapper XXXTentacion, and on his new album Quavo Huncho, Quavo of Migos chided a deceased drug user who many listeners took to be Lil Peep. The backlash to both instances voiced an ancient sense of outrage about of-the-moment ways. One tweet paired a pic of an angry Squidward from SpongeBob with the caption “When you have to explain Quavo and Vic Mensa that dissing dead people ain’t cool.”

The rappers seemed to realize they’d crossed a line. After the hashtag #FuckQuavo started trending, its target clarified that the subject of his song about reckless young rappers wasn’t Lil Peep and that he “N E V E R will speak on the deceased.” Vic Mensa taped a video saying he stands behind his lyrical condemnation of domestic abusers but didn’t mean to hurt XXXTentacion’s mother, who was in the audience at the BET Awards. Those delicate semi-apologies call to mind other recent instances of famous people tiptoeing to the edge of bashing the dead: Rose McGowan seeming to blame Anthony Bourdain for his demise even as she counseled doing just the opposite; Twenty One Pilots’ Tyler Joseph interrogating suicide victims in song while insisting he’s “not disrespecting what was left behind.”

It’s likely no coincidence that how to mourn—and how to prevent further tragedies—is at issue across pop culture right now. As the death rate in the United States continues to rise, fueled partly by spikes in suicides and overdoses and gun violence, the question of how to discuss lives taken prematurely will intensify. In each recent shocking celebrity death there are, plausibly, lessons—about mental health, substance use, social media, domestic violence, and other things—that might help curb the darker trends in American life. Can those lessons be heard and discussed without causing offense?

Vic Mensa’s BET freestyle weighed in on one of the touchiest issues of the past year: society’s worship of abusive men. While the #MeToo reckoning has haltingly spotlighted Hollywood’s creeps, reform in the music world has barely begun—and, in fact, some recent stories might indicate backsliding on sexual assault. XXXTentacion was a rising star with a horrifying rap sheet featuring allegations of beating a pregnant woman, charges of witness tampering and harassment, an admission of homophobic violence, and vile threats made to women on social media. When the 20-year-old was killed by robbers this past June, many critics tried to balance respect for a lost life with respect for the people he hurt in life. But fans went into sanctification mode, with many insisting that he’d been innocent all along, and others saying that he’d begun to atone for his behavior.

It’s unclear whether Mensa directly aimed at XXXTentacion in his BET freestyle. People who were at the awards show reported he had said, “Your favorite rapper is a domestic abuser / Name a single Vic Mensa song / XXX we all know you won’t live that long / I don’t respect n****s posthumously,” but the alleged “XXX” was omitted from the video eventually posted online. The line “your favorite rapper is a domestic abuser” could refer to a lot of folks, including Tekashi 6ix9ine, who pleaded guilty to three felony counts of “use of a child in a sexual performance” and who had earlier dissed Mensa by saying he couldn’t name a single song of his. But after backlash began to brew, Mensa didn’t deny that XXXTentacion was on his mind. “It was prerecorded weeks ago, and I had no idea a grieving mother would be in the audience to honor her lost son,” he said. “I never intended to disrespect her, and I offer my deepest condolences for her loss at the hands of gun violence. However, I vehemently reject the trend in hip-hop of championing abusers, and I will not hold my tongue about it.”

It is Mensa’s perceived break with manners—the calling out of a shooting victim in front of his mom—that appears to be generating the bulk of the blowback online. Others have cried hypocrisy, pointing out that Mensa once admitted to choking a girlfriend after she hit him, a situation he rapped about regretfully. Now he’s released “Empathy,” a conciliatory take on the criticism he faced. “I say what’s right, but they don’t hear me ’cause my past wrongs,” he raps between choruses about how he needs to work on his empathy. The song seems to recognize that the conversation has become about him as a messenger rather than about his message.

For Quavo, the alleged dis-of-the-dead happened on the way to addressing drug abuse and other dangerous behaviors. “Think you poppin’ Xanax bars, but it’s fentanyl / Think you’re living life like rock stars but you’re dead now,” he rapped on “Big Bro,” which also sneered about emcees who pose with guns on Instagram. Lil Peep, the emo-rapper who died at age 21 last November, was known to down Xanax bars and call himself a rock star. Of course, the same goes for lots of young artists—but Peep fans were nevertheless incensed. “No explanation will ever justify making someone’s death a diss line in their song,” went one of the many tweets tagged #FUCKQUAVO.

After Quavo shot back that Lil Peep wasn’t a target of his lyrics, he implied that he was really thinking about his barber, who died after taking fentanyl. “RIP TO ANYBODY WHO LOST THERE LIFE TO DRUG ABUSE!” he tweeted. Quavo thus asks that the song be seen not as a specific response to a specific tragedy, but as a general response to a general trend of substance use. Other rappers, such as J. Cole and Russ, have made antidrug messages part of their image, yet to hear it from a member of Migos, the rap trio whose lyrics have romanticized lean and other substances in the past, is fascinating. But the conversation around the song hasn’t been about whether Quavo is refining his stance; it’s been about whether he insulted a tragic icon.

The reasons not to speak ill of the dead are easily understood: They can’t defend themselves, and their loved ones are already in pain. And empathy—that trait Mensa now preaches—does matter. Moralizing about addiction without understanding it as a disease, or condemning abusers without examining the systems that created them, can be worse than futile. But there’s a hint of deflection in the defensive fan reactions to this past week’s earnest, if clumsy, attempts to talk about urgent problems. After all, Quavo and Mensa’s statements on some level were not about the dead but about the living: about the folks who might follow the same path as those who’ve died, and those who glorify stars for self-destructing. How to help those people before it’s too late makes for a more difficult conversation, perhaps, than the one about how to honor the departed.