A Dead Sea Scrolls Forgery Casts Doubt on the Museum of the Bible

Controversy over the dubious sourcing of artifacts has dogged the museum since its inception. Why hasn’t it learned its lesson?

The Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., has confirmed what many scholars have long suspected: Five artifacts it had been displaying as Dead Sea Scrolls fragments are probably forgeries.

The announcement, which came after several experts raised questions over the fragments’ authenticity, is the latest in a string of controversies that have plagued the museum over how it acquired its artifacts.

Jeffrey Kloha, its chief curatorial officer, said in a statement that this week’s revelation is “an opportunity to educate the public on the importance of verifying the authenticity of rare biblical artifacts.” And while that’s certainly true, this is also a lesson that the Museum of the Bible has had ample opportunity to learn before. Concern over the dubious sourcing of artifacts has dogged the museum since its inception.

The Green family, the evangelical owners of the craft-supply chain Hobby Lobby, started to collect artifacts pertaining to the Bible and its cultural context in 2009, with the goal of eventually founding the Museum of the Bible. In just four years, they amassed more than 40,000 artifacts, raising questions among scholars of the items’ authenticity and the possibility of illegal origins.

Many of the artifacts the Greens acquired lack provenance—documentation detailing their origin and history of ownership. Without this documentation, there’s no way to know that an artifact was not looted and sold on the black market.

A high-profile example of this came to light when the papyrologist Roberta Mazza discovered that the Green collection had acquired an unprovenanced fragment of the New Testament’s Book of Galatians that had previously been spotted for sale on eBay, where it was posted under a Turkish account. In 2017, Hobby Lobby was even forced to forfeit thousands of Mesopotamian artifacts and pay a $3 million fine after the U.S. Justice Department filed a civil forfeiture complaint against the company for illegally importing the artifacts from Iraq.

The revelation about the five Dead Sea Scrolls fragments reflects an ongoing tension between biblical-studies scholars and the museum. In their book Bible Nation, the scholars Candida Moss and Joel Baden criticized the Green organization for lacking “any sense of due diligence.” Judicious sourcing of artifacts is especially important given the rampant looting of archaeological sites in the Middle East in recent decades. Since the 1990s, hundreds of thousands of artifacts have been looted from Iraq alone.

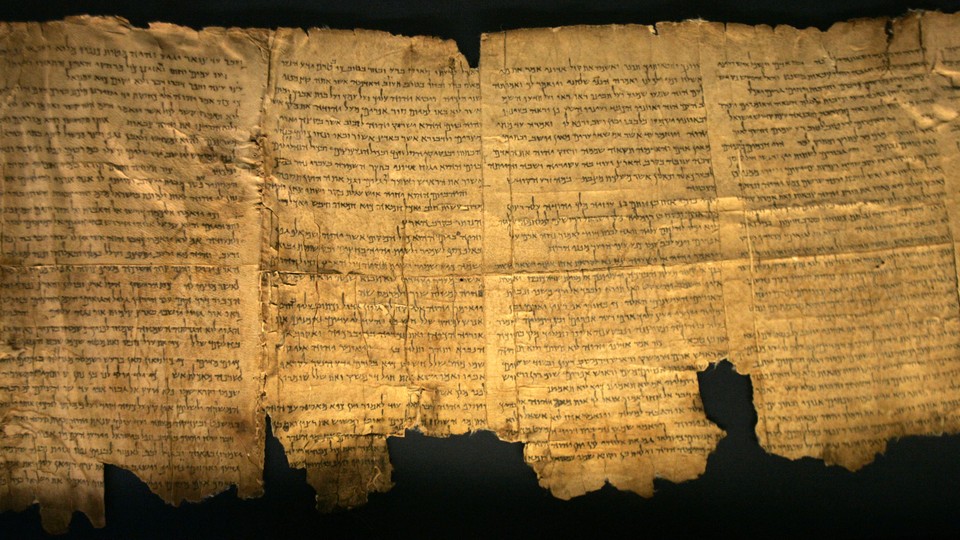

At this point, any recently discovered artifact being billed as an authentic fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls has to be met with cautious scrutiny. Dozens of unprovenanced Dead Sea Scrolls fragments have come to light since 2002. They are a favorite among forgers, perhaps not least because the collection of 900 mostly fragmentary scrolls was hailed as one of the most significant archaeological finds for biblical studies after it was discovered in the 1940s and ’50s in caves around Qumran in the West Bank. Many of the texts discovered were fragments of well-known passages from the Hebrew Bible, while others were previously unknown passages that shed light on Judaism during the Second Temple period.

Archaeologists have long argued that when it comes to forgeries, the supply continues because the demand is there: So long as organizations like the Museum of the Bible are willing to purchase and display these artifacts, they will continue to be offered up on the market.

It’s worth noting, though, that it’s sometimes very difficult to detect forgeries, even when using the same scientific methods of analysis recently applied to the museum’s Dead Sea Scrolls fragments. Forgers have been known to write text on scraps of authentically ancient papyrus. That appears to have been the case with another infamously unprovenanced fragment, the so-called Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, which came to light in 2012. Radiocarbon dating determined that that fragment was from the late-antique or early-medieval period. But on the strength of scholars’ textual analysis and the journalist Ariel Sabar’s investigation tracing the fragment’s chain of ownership, it was ultimately widely conceded to be a modern forgery.

The Museum of the Bible has now removed the five Dead Sea Scrolls fragments from display. Kloha, the chief curatorial officer, said the museum remains committed to transparency. But has the museum learned its lesson? It has said it will replace the five fragments with “three other fragments that will be on exhibit pending further scientific analysis” and that “labels will continue to inform guests that there have been questions raised about the authenticity of these fragments.”