The full extent of the damage caused to artefacts by the devastating fire at the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro will take some time to emerge. A spokesman for the fire brigade told Globo News: “We were able to remove a lot of things from inside with the help of workers of the museum,” leading to hopes that at least some of the collection may have survived. Pictures surfaced on social media showing people carrying small items out of the burning building.

Below are some of the scientific and historical highlights of a collection of over 20m items, whose loss was described as “incalculable” by Brazil’s president, Michel Temer.

Luzia Woman

Luzia Woman is an upper paleolithic period skeleton that was found in a cave in Brazil in 1975 by the French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire. At about 11,500 years old, she was believed to be the oldest human skeleton found in the Americas.

Debate has raged about her origins, with some anthropologists suggesting the skull showed signs that Luzia’s ancestors had come to the continent from south-east Asia. She would have stood at just under five feet tall.

In 2010, scientists reconstructed how her face may have looked in real life.

Mummified remains

Donated to Emperor Dom Pedro II, the second and last monarch of the Empire of Brazil, the museum’s collection included a rare Brazilian example of mummified bodies, belonging to a woman and two children. The woman, found in Goianá, was aged about 25, and died 600 years before Europeans arrived on the continent.

The museum also held mummified or shrunken heads produced in the Ecuadorian Amazon basin by the Shuar people. In the heavily ritualised processes, the skull was removed while leaving the skin and hair intact.

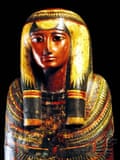

From further afield, the museum was also home to 700 items from Egypt, including the coffin of Sha-Amun-em-su, an unopened wooden painted coffin from Thebes, dated to around 750BC. X-rays of the item show that as well as the body, there are amulets still intact inside the casket. Other Egyptian relics in the museum included the 3,000-year-old coffin of the priest Hori and a mummified cat.

Indigenous art and artefacts

Established in 1818, the museum’s collection preserved irreplaceable art and objects from Brazil’s indigenous peoples. They tell the tale not just of the people who lived on the continent, but of how they were encountered and occupied by European colonists.

Some of the items in the museum were collected when Marshal Rondon was driving telegraph lines and roads through the Amazon basin in the early 20th century. As well as collecting weapons, the Rondon Commission also collected musical instruments, and in 1912 the anthropologist Edgar Roquette-Pinto, who accompanied them, made the first recordings of indigenous music on wax cylinders.

From contemporary native populations the museum held striking feather art by the Karajás people, as well as examples of their ceramics. Only about 3,000 of the Karajás survive, living in a few dozen villages in central Brazil.

The collection included a total of about 1,800 artefacts from the pre-Colombian era, including pieces from Andean cultures such as the Inca, Chancay and Nazca civilisations that illustrated textile and ceramic manufacture, and evidence of trading behaviour. A mummy of a Chilean man estimated to be at least 3,500 years old gave an insight into how people were buried – in this case in a seated position with the knees raised up to the chin.

The museum’s director, Alexander Kellner, said of the fire: “It is a pitiful tragedy. Inside it there are delicate and inflammable pieces, a fabulous library. The collection of the museum is not for the history of Rio de Janeiro or Brazil, it is fundamental to world history.”

Bendegó meteorite

The Bendegó meteorite, at 5,260kg, was the biggest iron meteorite found on Brazilian soil, and at one point the second largest ever found in the world. It was discovered in 1784 in Monte Santo, Bahia by a boy, and is one of the largest such items ever to be transported.

Frescoes from Pompeii

Frescoes that survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius were also in the museum’s collection, including one depicting two peacocks perched on stylised chandeliers, and two others featuring seahorses, a dragon, and dolphins, which originally adorned the Temple of Isis in Pompeii. With 750 pieces from Mediterranean culture in the collection, it was the largest grouping of such artefacts in Latin America.

Fossil records

Described as “a palaeontological paradise of international significance”, the Sertão region of Brazil has been particularly rich in fossils, enriching the museum with a large collection. Fossilised turtles from 110m years ago that were in the collection are the oldest found in the country.

The Angaturama limai dinosaur in the collection was also discovered in Brazil. The name is derived from the indigenous Tupi language, and is a tribute to the Brazilian palaeontologist Murilo Rodolfo de Lima, although there is some debate as to whether the fossil belongs to a previously identified species, the Irritator challengeri.

The creature was a fish-eating type of carnivore with a “sail” along their back. These fossils have close relatives in African fossil deposits, supporting the theory the continents of South America and Africa were linked. The specimen was the first large Brazilian carnivorous dinosaur to be displayed.

Also on display was a replica of a Maxakalisaurus topai dinosaur skeleton – the largest scientifically identified sauropod found in Brazil. The palaeontologist Alexander Kellner had said at the time of the discovery: “We have found the bones of what appear to be larger dinosaurs, but we still haven’t been able to put them together for scientific descriptions.”

The museum’s fossil collection was not just a record of the natural history of the continent, but also of the study of natural history in the South Americas in general. The museum, for example, housed Brachiopods, the first fossils of the Devonian period – approximately 390m years ago – that were collected and studied in Brazil in the 1870s.

Scientific library

The museum was home to a scientific library that contained nearly half a million volumes, including 2,400 described as rare works. Social media reports suggested that people were finding burnt pages in the streets around the museum.

- This article has been amended to clarify that the director of the museum is Alexander Kellner.