As a prolific social critic covering topics from AIDS to American interventionism, Susan Sontag seemed almost fated to run afoul of the Bureau. Although her association with the “New Left” of the 1960s first put her on the FBI’s radar, it was her writing in opposition to the Vietnam war that earned her her own investigation and the personal attention of no less than Director J. Edgar Hoover.

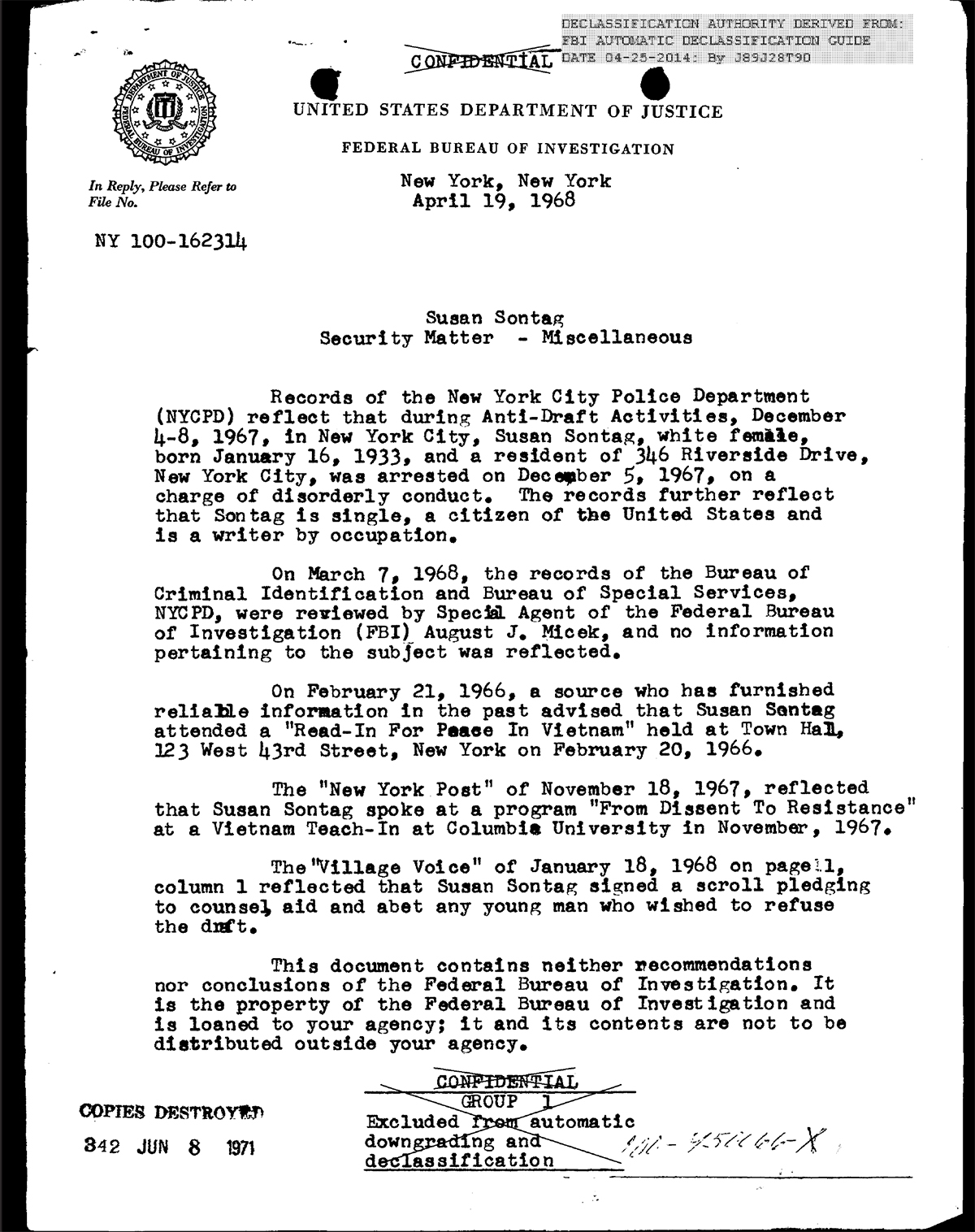

Sontag’s file begins in early 1968. By this point Sontag had already participated in several antiwar demonstrations, including a 1966 “Read-in for Peace” alongside several other New York authors and a three-day protest of a Selective Service station in 1967 that ended in her arrest for “Disorderly Conduct,” none of which escaped the attention of the Bureau, who noted these activities in a “Security Matter” file categorized as “miscellaneous.” Through infiltrators and informants within the antiwar movement, the FBI received a tip that Sontag had visited Hanoi at the invitation of the North Vietnamese government—a violation of her passport’s restriction on visiting communist countries—but lacking evidence, the special agent in charge of the New York Field Office recommended no further investigation unless advised contrary.

A few months later, they were advised contrary and then some. The New York Field Office was told to have a full report on Sontag’s travel in two weeks, with Hoover himself demanding that the case be given immediate attention. What had happened in the meantime to warrant this sudden interest in Sontag?

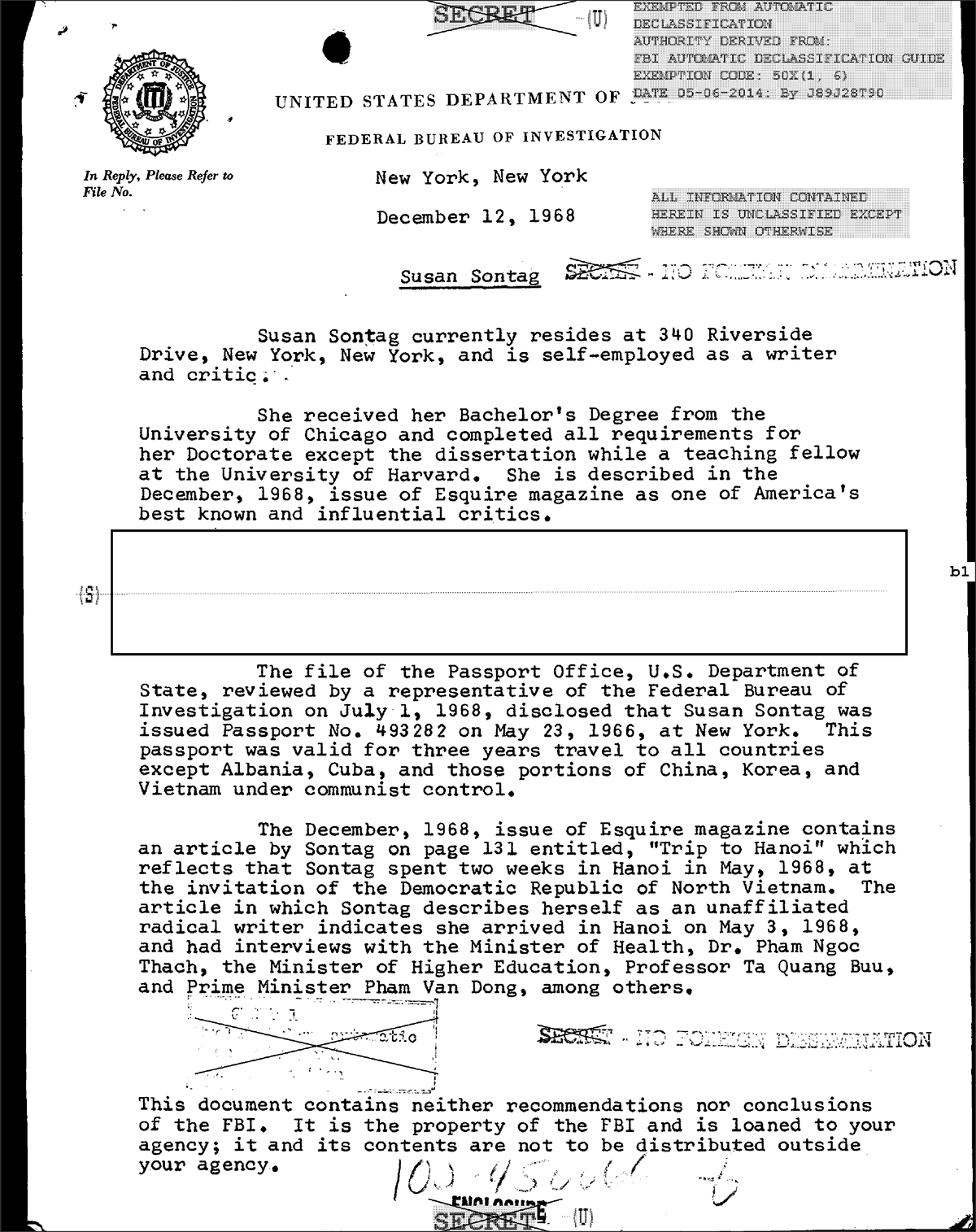

The Bureau had received credible evidence regarding Sontag’s trip to Hanoi—a feature in Esquire describing her experiences talking to leading figures of the North Vietnamese government, including Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, that would later be adapted into the book Trip to Hanoi.

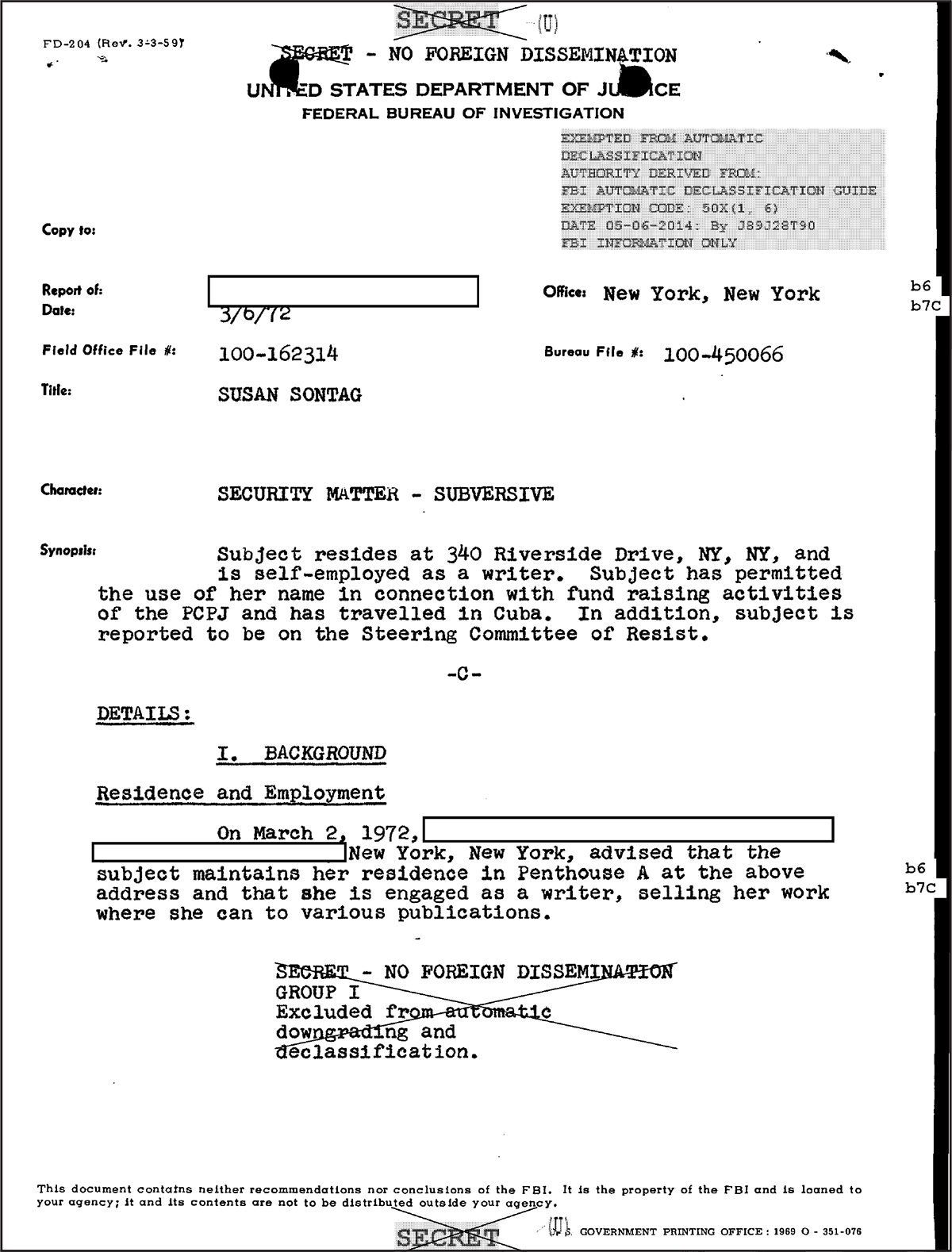

Though the New York office did produce a comprehensive report on the origins of the article and all of Sontag’s previous antiwar activity (citing a total of nine informants, whose names remain redacted) within the two week deadline, the investigation into Sontag stretched on for another two years. A 1971 memo from the Department of State confirmed that Sontag hadn’t sought or received permission for her travel to North Vietnam, and another memo from what appears to be French intelligence was passed on from the CIA.

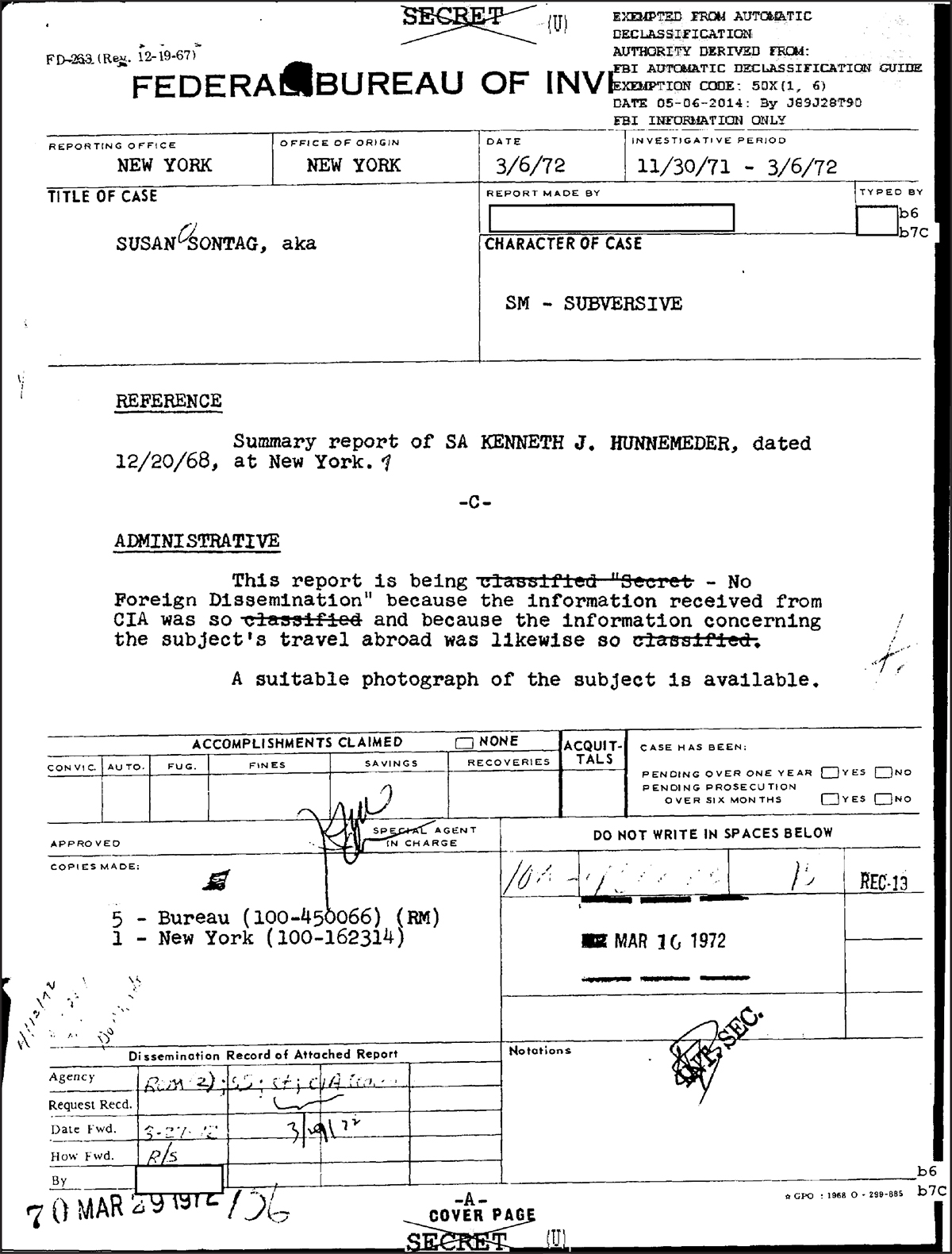

A final report dated in March of 1972 upgrades Sontag’s “Security Matter” to full-blown “Subversive,” and offers two conclusions. First, it was not recommended that the Bureau interview Sontag on, on account of her “status as a writer” which “could result in embarrassment. Second, her activities, though indeed subversive, were not enough to qualify for her inclusion into the ADEX, the FBI’s “Administrative Index,” of people “considered to be a threat to the security of the country.” Similar to Allen Ginsberg, Sontag was deemed more of an irritant than a danger, and for the second time in four years her file was closed. Hoover’s death a little over a month later ensured it would stay closed.

Click any of the following documents to enlarge.

From Writers Under Surveillance: The FBI Files, ed. JPat Brown, B.C.D. Lipton, and Michael Morisy. Used with permission of MIT Press. Copyright © 2018 by Massachusetts Institute of Technology.