Seventy-three thousand years ago, an early human in what is now South Africa picked up a piece of ocher and used it to scratch a hashtag-like mark onto a piece of stone.

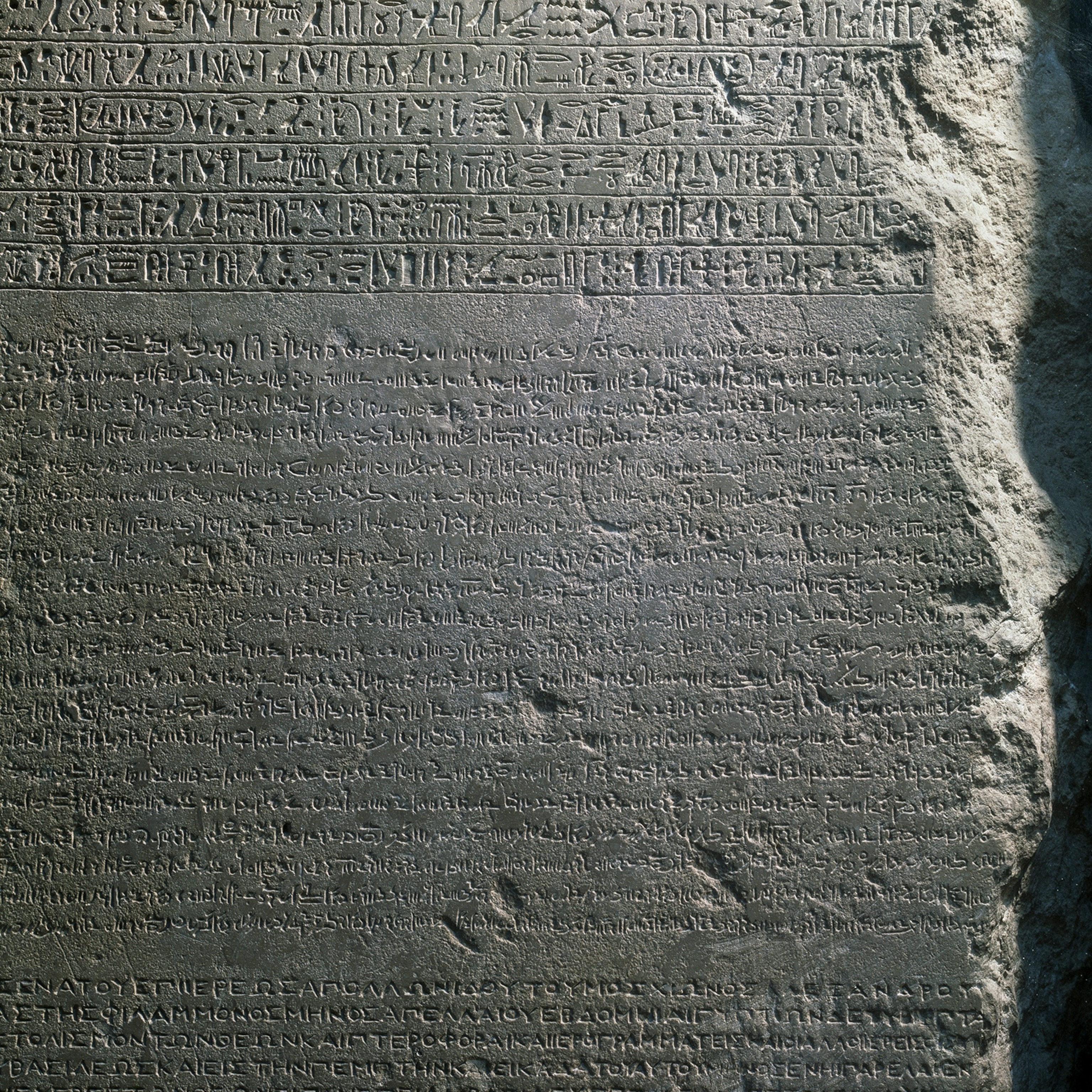

Now, that stone has been discovered by an international team of archaeologists who are calling it the earliest known drawing in history.

According to their report, published today in the journal Nature, the stone predates the previous earliest known cave art—found in Indonesia and Spain—by 30,000 years. That would significantly push back the emergence of “behaviorally modern” activities among ancient Homo sapiens.

But how solid is the find, and can it really be labeled as art? Here’s what you need to know about the discovery and its possible implications.

What did the scientists find?

The archaeologists found a smooth flake of silcrete, a mineral formed when sand and gravel cement together. The inch-and-a-half-long flake is covered in scratch-like markings made with ocher, a hardened, iron-rich material that leaves behind a red pigment.

Where was the stone discovered?

The team found the flake of stone in a dense deposit of artifacts that early Homo sapiens left in Blombos Cave, which lies about 185 miles east of Cape Town, South Africa. Nestled inside the face of a cliff overlooking the Indian Ocean, the cave seems to have given small groups of humans a place to rest for brief periods before they headed out to hunt and gather food.

About 70,000 years ago, the cave closed, sealing in the artifacts from these visits. The cave opened and closed again over the years as sea levels and sand dunes rose and fell, and that did archaeologists a big favor by sealing the cave instead of letting its contents be swept away by the sea.

“The preservation is absolutely perfect,” says the paper’s author, Christopher Henshilwood, an archaeologist who heads up the Center for Early Sapiens Behavior at the University of Bergen. Henshilwood, who has previously received National Geographic grants, has conducted digs at the site since the 1990s.

Inside the cave, scientists have found other evidence of Homo sapiens being crafty from as far back as a hundred thousand years ago. Discoveries so far include perforated shells that archaeologists think were used as beads; tools and spear points; pieces of bone and ocher with scratched faces; and a group of artifacts that seems to point to production of a liquid form of ocher pigment.

Why do researchers think this stone is important?

The discovery shows “that drawing was part of the behavioral repertoire” of early humans, the researchers write. If people were making paints, stringing beads, engraving patterns on bones, and drawing, then they were behaviorally modern as early as 70,000 years ago, and perhaps earlier, Henshilwood says.

“It’s the fourth leg of the table,” he says. The same types of evidence have been used to show the development of early modern humans in Europe, he points out.

Do other experts agree with their conclusions?

“This is well dated,” says Margaret Conkey, an archaeologist and professor emerita at the University of California, Berkeley, who has extensively studied cave and rock art. “The context is good. They've been working on this stuff for many years. They're very thorough.”

However, says Conkey, she takes issue with the interpretation that modern behavior first arose in southern Africa. “They're focusing on an Afrocentrism,” she says, which challenges a view that puts the origins of behavioral modernity in Europe. (Here’s evidence of the oldest modern human found outside Africa.)

“Neither centrum is good, because human evolution and behavior are complicated,” she says. “There is no one single origin.”

Researchers call the artifact a “drawing.” But is it art?

“We don’t know that it’s art at all,” says Henshilwood. “We know that it’s a symbol.” But since the stone flake has similar cross-hatchings as the ones found on bones and pieces of ochre in Blombos, he does believe the design was deliberate. “Art is a very hard thing to define. Look at some of Picasso’s abstracts. Is that art? Who’s going to tell you it’s art or not?”

But Conkey thinks the wording chosen by Henshilwood and his team points to a particular interpretation, especially when it comes to the way they describe the ocher used to depict the hash marks. “They’re calling it a crayon,” she says. “That automatically leads you to think they’re drawing something. Why not be a little more neutral and call it a piece of ocher?”

Conkey sees the use of words like “drawing” and “crayon” as rhetorical tools used by Henshilwood and his team to imply that the early humans’ behavior was, in fact, modern. She sees the hash marks as perhaps nothing more than a doodle—an example of an early human engaging with the world around them.

Did the early human pick up that piece of ocher deliberately? Was it meant to portray an object or even an abstract concept? Without a time machine, we’ll never know. Nevertheless, says Conkey, “this is exciting stuff. This adds to the complexity of the material record from early Homo sapiens in South Africa.”

Related: Pictures That Capture the Wonder and Thrill of Archaeology

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital