The generations-long battle to have artworks stolen by the Nazis restored to the original owners or their heirs teaches many lessons about cruelty, greed and the failure to reckon with the past on the part of foreign governments and art museums.

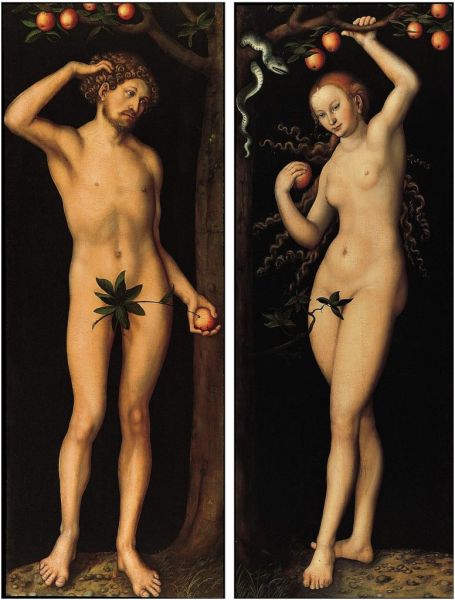

On July 30, a three-judge panel of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision to permit the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, to keep a pair of oil-on-panel paintings by Lucas Cranach The Elder (1472-1553), Adam and Eve, which had been among hundreds of paintings confiscated from the Dutch Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker by Hermann Göring after the German invasion of the Netherlands in 1940. This ruling on the pair of oils, which were eventually sold to Norton Simon himself in 1971, offers yet another such lesson, this in the Act of State Doctrine.

The historical facts are not in dispute: Goudstikker worried about a German invasion of Holland in the late 1930s when he applied for an American visa, and he and his wife were able to book passage on one of the last ships to depart the country, leaving all the contents of his gallery in the hands of two of his employees. Unfortunately, the dealer himself died aboard ship, falling through an open deck hatch and breaking his neck. A forced sale turned over the majority of the 1,241 artworks to Göring. Shortly after the war, Goudstikker’s widow, Desi, returned to the Netherlands to seek compensation for the lost property, involving her in litigation with the Dutch government to whom the Allied Forces had returned paintings captured from the Germans.

In 1952, Desi reached a settlement with the Dutch government, returning to her not the actual artworks but the supposed purchase price paid for them by Goring. By 1997, the Dutch acknowledged that it had acted unjustly but, when Desi’s daughter-in-law, Marei Von Saher, appealed the 1952 settlement, she was told that the family had relinquished her claims back then.

Under the Act of State Doctrine in U.S. law, which says that every sovereign state must respect the independence of every other sovereign state, the California court ruled that it would follow the Dutch government’s decision that the 1952 settlement conferred good title to the Netherlands. That decision then legitimately permitted the Dutch government to sell the two Cranachs in 1966 to George Stroganoff-Sherbatoff, who sold them to Norton Simon five years later. The California ruling stated that “the act of state doctrine deems valid the Dutch government’s conveyance to Stroganoff,” which means that “the Museum has good title. Holding otherwise would require us to nullify three official acts of the Dutch government—a result the doctrine was designed to avoid.”

“This was a complicated case, and I wasn’t surprised by the result,” said Nicholas O’Donnell, a partner in the law firm Sullivan & Worcester and the author of A Tragic Fate: Law and Ethics in the Battle over Nazi-Looted Art. “The 9th Circuit accepted the case in order to say that the U.S. courts wouldn’t revisit an issue that had been resolved by the Dutch government. That would be considered an insult to international relations.”

The sale of the Cranachs to Stroganoff-Sherbatoff, he claimed, was considered a “sovereign act, something that only a nation can do, as opposed to a commercial act, which would be a private sale by one individual to another.” The degree to which the California appeals court ruling may have bearing on other instances where U.S. museums have Holocaust-era artworks in their possession on which claims might be made is limited. However, “it will continue the debate over which kinds of transactions warrant judicial review,” said O’Donnell.

A somewhat more sanguine view of the July 30 ruling was expressed by New York art lawyer William Pearlstein, who called the decision “fact-specific and law-based. The court acted in a neutral manner, which you want. It was a little bloodless, perhaps, due to the Holocaust context, but as a legal matter it was altogether appropriate to defer to the lawful authority of a foreign government.”