On the Doha corniche, on the route into the city from its airport, a monumental pile of fibre-cement discs is nearing completion. It is the new National Museum of Qatar, where the country’s “cultural heritage, diverse history and modern developments” are to be displayed. It will, says its silver-tongued Parisian architect Jean Nouvel, “symbolise the mysteries of the desert’s concretions and crystallisations, suggesting the interlocking pattern of the blade-like petals of the desert rose”. It does indeed look like the clusters of sandy crystals that go by that name.

This is the same Jean Nouvel whose outpost of the Louvre opened last year in Abu Dhabi, which for now is one of Qatar’s enemies. He also designed the 238-metre Burj Doha, completed in 2012, which is from the same genre of anatomically suggestive towers as his Torre Glòries in Barcelona and Norman Foster’s Gherkin in London. The burj is the most memorable building in an instant downtown called West Bay, an extravagantly variegated constellation of vertical glass of a type now familiar from China to the Gulf to the US to London.

The museums and towers are at once expressions of progress and weapons in a cultural and architectural arms race. They combine good intentions and political calculation. They are signs of a hunger for identity and status in lands transformed within a lifetime by oil wealth. They are currency in the tricky and obscure negotiations that the leaders of the Gulf nations conduct, between conservative forms of Islam, authoritarian rule and selective versions of western liberalism. These states are surrounded by convulsions and conflicts in which they are themselves implicated, while aiming at home for prosperity, stability and the survival of their ruling regimes.

The physical transformations are manifestations of a fantastically speeded-up version of the processes by which cities were historically made, an evolution at x64 speed from small coastal towns to metropolises furnished with skyscrapers and universities. It is hard to overstate how radical this change is: these regions were at the limits of human habitation, made harsh and lightly populated by extreme heat and aridity. Oil and air conditioning have brought both physical comfort and influxes of migrants and expatriates, but the numbers of native Emiratis, Qataris and Kuwaitis remain small. There are, for example, 300,000 Qatari citizens, which is rather less than the 580,000-odd population of Luxembourg.

As one involved in their development puts it, these are “very small populations with very big ambitions”. They find themselves with power and influence disproportionate to their size, beyond the imagination of recent generations and outside the scope of traditional mechanisms of government. Their cities are therefore works in progress, raw and unprocessed, in which assertions of possible futures jostle for priority. Readymade chunks of imported building types – malls, museums – appear without much thought to the spaces between them. And, always, they need to deal with the environmental factor that governs everything else in the region: sheer, overwhelming, dominating heat.

Gulf cities and states are, importantly, not identical. Dubai and Abu Dhabi, though both within the United Arab Emirates, differ, the former favouring tearaway private enterprise, the latter more stately public investments. Qatar, with works such as the 2008 Museum of Islamic Art, has been the most consistent patron of culture. Oman, seeking to stay out of trouble, is the least ostentatious. A number of these states are currently in conflict – Qatar is the subject of a blockade by several neighbours on the grounds that it supports extremism and terrorism. Coming from the likes of Saudi Arabia, this accusation is rich.

At the same time, Gulf cities follow similar patterns. They have been through identifiable phases, starting 60 years ago when they were still coastal towns, clinging to the margin between sea and desert, living off fishing, pearl-diving and/or piracy. Their low buildings, mostly built of mud and rubble, huddled against the heat. Bahrain airport, recalls one who knew it in the 60s, consisted of two Nissen huts, one for buying Coke and another for getting your passport stamped.

In the 70s and 80s came an influx of hotels and office blocks, mostly by western architects, who added Arab styling and space age flourishes to generic corporate boxes. From the 90s onwards, Dubai pioneered the attention-grabbing landmarks, Instagram-friendly avant la lettre: the sail-shaped Burj al Arab hotel, the artificial islands shaped like palm trees and a map of the world, culminating in the pride and hubris of the tallest building on the planet, the 830-metre Burj Khalifa. Others follow similar paths – a pearl-shaped island in Doha, for example, and that Nouvel tower.

This century has seen the rise of the sporting icon – the stadiums for Qatar’s 2022 World Cup, the Formula One circuits in Abu Dhabi and Bahrain that manage to make races look weirdly like computer game versions of themselves – and of the cultural icon, the Louvre Abu Dhabi above all. Famous brands such as Formula One, Fifa and the Louvre are supported by the branded styles of the most famous possible architects – Nouvel, the late Zaha Hadid for one of the football stadiums, Frank Gehry for a currently stalled Abu Dhabi Guggenheim. All are winners of the Pritzker prize, the most prestigious of their profession, the widely recognised imprimatur of the iconicity of an architect.

Both the trading of respected cultural names and their reinforcement by iconic architecture are games developed elsewhere in the two decades since Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim started them off in northern Spain. But the Gulf countries play them with particular aplomb. The deal for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, whereby name, expertise and exhibits are being lent in return for (it is reported) a billion or so dollars, is the most audacious yet, both because of the great fame of the mother museum and the previous improbability of seeing canonical classical painting and sculpture in this Muslim desert emirate. It is also one of the most spectacular and, by many accounts, successful works of Nouvel’s hit-and-miss oeuvre, with dappled light filtering through a great perforated dome into courts cooled by pools of water. “An Arabic-Galactic wonder”, wrote the New York Times.

The exact purpose of this magnificence is a subject of debate. At one level, the Louvre does what great museums do everywhere, which is to give the public access to the beauties of art and to a shared social space. It gives another dimension to the somewhat depthless cultural life of what is mostly a very new city. Jonathan Jones, art critic for the Guardian, saw it as “a turning point in cultural history… to create a new global museum in the Arab world with an Arab perspective is a revolutionary subversion of the old European imperialism of knowledge”.

It would, however, be naive to see this (or any major museum, the original Louvre included) as an expression of pure love of either art or the common people. The wealthy dynasties who rule the United Arab Emirates and the other Gulf states have their reasons for such huge investments, such as the stabilities of their societies, their perception abroad and their continued grip on power. According, for example, to Alexandre Kazerouni, a French academic of Iranian origin, projects like the Louvre are about strengthening the authority of the ruling classes by putting culture within their control. He also points out, in his book Le miroir des cheikhs, that the funds for Abu Dhabi’s cultural projects come from payments foreign governments have to make when they sell the UAE arms, which are managed by something called the Offset Program Bureau.

Similar complexities arise in Doha, where, in a grand ceremony in April, the emir inaugurated the Qatar National Library. I was one of a group of foreign journalists flown in by the Qatar Foundation. Tech guru Nicholas Negroponte, who once declared the death of the book, was paid a reportedly vast fee to speak for a few minutes on how, after all, the book was still alive. The former French president Nicolas Sarkozy mingled with other eminent guests. If the event was ruffled by a denunciation of authoritarian power from the Palestinian poet Tamim al-Barghouti, it was soothed again when it became clear that he was referring to Israel.

The library is the culmination of more than two decades of patronage of education projects led by Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser al-Missned, whose husband, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani, was the ruling emir of Qatar until he stepped aside in 2013. The sheikha has received more than her share of puff and guff, getting called a “glamorous ambassador”, “the actual ruler of Qatar” and, in the Huffington Post in 2011, “First Lady of the World … a doting mother, a global visionary and an international inspiration”. She has achieved both a George Bush award for excellence in public service and an induction into the Vanity Fair international best-dressed hall of fame.

Since 1995, Sheikha Mozah has been head of the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development, an organisation that has created Education City, a zone of 14 sq kms that contains branches of such major academic institutions as University College London, Georgetown University and the Weill Cornell Medical Center. Masterplanned by the Japanese architect Arata Isosaki, the complex also includes schools, an equestrian centre, well-tended parks and a mosque designed by London-based practice Mangera Yvars in a style of “Islamic modernity”, whose swooping, soaring, organic lines try hard to resemble as little as possible traditional motifs of dome and minaret.

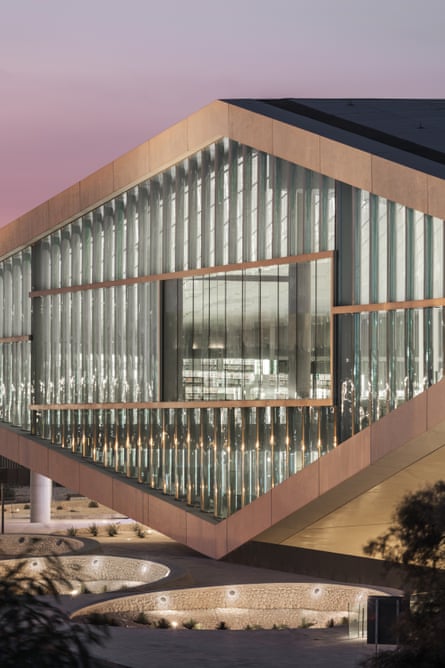

Brooding like a rectangularised brain over one end of Education City is the headquarters of the Qatar Foundation, an inscrutable whitish cube perforated by square openings and sliced by a long horizontal slit. Designed by the Dutch practice OMA, it suggests both fortified power and a complex intelligence that may or may not be benevolent. Towards the middle of the campus is the national library, also by OMA, a dynamic lozenge whose corners are raised off the ground to create sheltered approaches underneath. The library’s intentions, in contrast to the HQ, are about openness. “It is about access to everyone, from a six-year-old child to an 80-year-old researcher,” says Sheikha Hind bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Sheikha Mozah’s daughter, who is vice-chairperson and CEO of the foundation.

The aim is to create “a place where a community can gather”, as Ellen van Loon, the OMA partner in charge of the project puts it. “We want children to run and shout,” says Ibrahim al-Jaidah, an architect who works with the foundation. “We want their voices to be heard.” The library thus becomes a kind of civic place in an area where summer temperatures of 40-50C make European-style public squares quixotic and the shopping malls, with their mechanical coolness, become the main zones of gathering. The library, like a mall, is a managed space, but less controlling in its experiences and less prescriptive in its products.

“The idea of a library has changed,” says Rem Koolhaas, OMA’s Pritzker-winning leader, “from a place that imprisons books to one that is a place of learning in any way you like.” The design creates an “arena” in which shelves full of the those humble-looking and allegedly endangered objects – books – rise up in great shallow terraces under a single ceiling, in what OMA says is the biggest single room it has so far created. A “theatre” it also calls it, in which books occupy the space of spectators and readers that of actors.

There are subtleties and inflections within this simple idea, its grandeur unbending enough to allow more intimate spaces for reading the books once you’ve picked them up from the open-access shelves. A primary condition of architecture in these regions is expanse – the feeling that terrain continues indefinitely into the desert, that a settlement might as well be elsewhere as somewhere and can therefore seem both puny and random. The library deals with this phenomenon nicely, by extending views to the horizon through glass walls, while also suggesting a distinct place through its folds and surfaces. It implies more than encloses, as a landscape does.

Reflective surfaces in ceiling and floor multiply the inner life of the building. In the centre, formed out of the ground like an archaeological dig, are marble-lined spaces containing a collection of rare books and documents. It is a moment of rootedness, a symbolic foundation in a building that elsewhere wants to levitate. It adds another element to a building that Koolhaas calls “almost Roman in its dimensions”, that is “transparent” but has “depth”. “You could therefore live in so many worlds in this volume,” he says.

It’s a striking-looking object that flirts with the easy metaphors that tend to thrive in locations parched of historical references – a Bedouin tent, a spaceship – without succumbing to them. For me, it’s part of the design’s skill that it engages with the Gulfian desire for spectacle while also realising a serious idea of what a library might be. Koolhaas bristles, however, at the implication that this might be another in the world’s ever more wearying list of architectural icons. “It’s a very direct approach to making reading more attractive,” he says. “It’s about generosity rather than spectacle.”

The Qatar National Library poses, as does the Abu Dhabi Louvre, the great Gulf question: to what extent is this institution, which embraces the ideals of the European Enlightenment, for real? To what extent is it a vast act of sophisticated PR and soft power, part of a game of influence that also includes patronage of al-Jazeera and the acquisition of property landmarks such as the Shard in London? How far can it go, in a country where homosexuality is a crime and the government supports Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist Islam?

Sheikha Hind says the Qatar Foundation wants to “encourage a generation that will debate and think for themselves”, but how free can they be when her family is permanently in charge of culture, government, business and city planning? All over the city, storeys-high on buildings and on the sides of cars, are emblazoned stylised images that portray her brother, the reigning emir, somewhat firmer-jawed and more dashing than in reality, as an unlikely sort of Che Guevara. The story is that this image, known as “Tamim the Glorious”, is the creation of a local artist that was spontaneously adopted by the Qatari people. But giant images of rulers tend not to be signs of open societies.

Then there is the question that rightly dogs every building project which claims to be progressive – the region’s notorious labour practices, whereby migrant workers are deprived of rights and can lose their lives on dangerous sites. Architects involved in Gulf projects tend to express both regret and the view that things are getting better, but that there is not much they can do about it.

Many questions you ask receive answers satisfying to a European liberal. Does the library contain Lolita and the works of Salman Rushdie? I ask its executive director Sohair Wastawy. Yes, she says. And 60% of students in Education City, says Sheikha Hind, are women. Koolhaas says he has never worked on a building project where so many of the leading decision-makers were female. Qatar, along with other Gulf countries, is generally considered to be highly patriarchal.

There is much to like, too, about the newest phase of Gulf urbanism, which is to challenge the car-based and energy-hungry imitations of north American cities that have dominated until recently. Abu Dhabi has for some time been building the Foster-designed Masdar City, a satellite that aims for exemplary sustainable design and planning. In Doha, the Qatar Foundation is trying to revitalise the oldest part of the city with Msheireb, a development between the country’s seat of government, the Amiri Diwan, and the main souk. The British architect Graham Morrison, whose practice Allies and Morrison helped design it, calls the project a “game-changer”. In West Bay, the skyscraper district that includes Nouvel’s Burj Doha, you can’t walk from one building to another across the multi-lane highways. In Msheireb, the aim is to adapt traditional principles to achieve an environment in which it is pleasant to walk, achieved with the help of natural means.

Shade and wind direction are used, as in traditional Arab cities, to lower the temperature, along with technology that uses the spare cooling capacity of the air conditioning that, inevitably, is used inside the buildings. A square, shaded by something resembling horizontal Venetian blinds, creates a type of outdoor gathering space not seen before in these parts. A consistent palette of off-white stone and render is used throughout, to create what Morrison calls “a proper piece of city-making”.

Much of the approach could be called common sense, the application of good practice with the help of budgets that allow a degree of quality in the finishes, except that it is something not much seen in the Gulf or indeed in many other parts of the world until now. He calls Msheireb “several steps in the right direction” and a “platform” for the future development of Middle Eastern cities. As evidence, he cites Madinat al Irfan, a much bigger project in Oman, on which Allies and Morrison are working. Here, a residential population of 60,000 people are to be housed along similar principles to Msheireb’s.

“What’s not to like?” asks Morrison about the investment of oil wealth in good city building. Msheireb, the library and the Louvre Abu Dhabi walk the walks of their cultural proclamations enough that they should not be easily reversed. “I find it surprising that countries such as Qatar and the Emirates,” Koolhaas has said, “are attacked when they are trying to make Islam and modernity compatible.” The Louvre Abu Dhabi gets criticised, he tells me, for only showing “three naked men.” But “you could say it’s fantastic to have that many.”

The New Yorker, in an article on the ethical issues of Gulf art projects, quoted the take of Mishaal al Gergawi, an Emirati intellectual, on his government’s perspective: “You sit there on the throne, thinking, My country is only 45 years old and I’m trying to fight Isis, develop a post-oil economy, foster a tolerant society by building museums and universities, and I’m getting criticised for labour issues? Give me a break.”

The dilemma in other words is that posed by China, or Azerbaijan or any number of repressive regimes, which is whether it is better to avoid or engage. Should well-intentioned and influential outsiders refuse to legitimise what should be challenged or might they hope that (for example) the conditions of migrant workers will be improved through the attention brought by the Louvre and the World Cup? Does the presence of Nabokov on the library shelves outweigh governmental support for extremism? Where on the scale from Faustian to Abrahamic is the bargain being struck?

The truthful answer is that nobody knows, including those ruling families who are playing multi-sided games of which libraries, universities and museums are part. Because these games are ongoing, their outcome uncertain and because these families and the societies they rule are not themselves homogeneous but contain different aspirations and ambitions. What can be said is that these cultural and architectural projects are, in themselves, for the good. There doesn’t seem much to be gained by wishing they weren’t there.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion