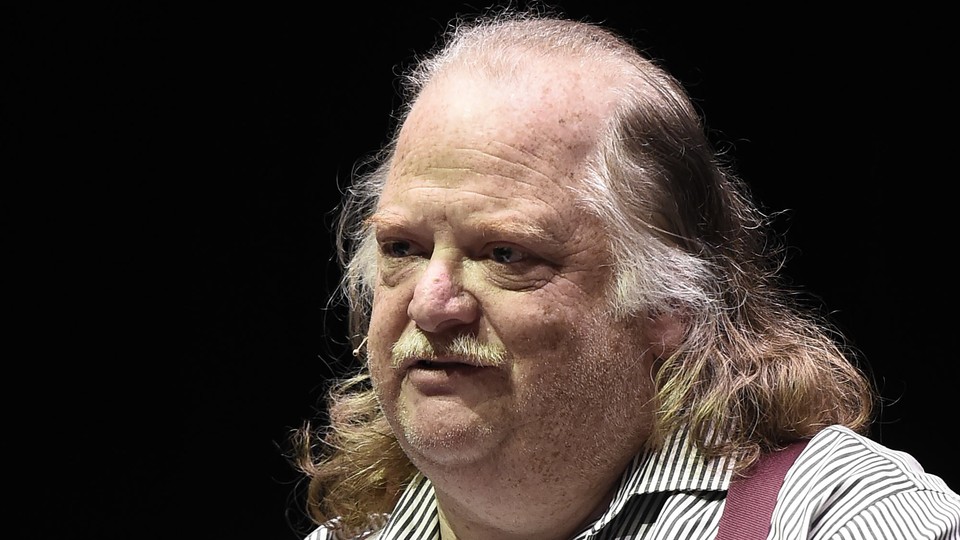

Remembering the Inimitable Jonathan Gold

The beloved critic, dead at 57, was the first food writer to win a Pulitzer Prize—and a vital champion of L.A.’s culinary riches.

Every so often, I would send the food critic Jonathan Gold a fan note when one of his pieces seemed even better written than usual. He would always reply with something gracious like “Too kind, as always,” or with a reciprocal compliment for a piece of mine he’d happened to see. What I never said and always meant was, “Reading your latest piece made me think, as I always do the minute I start anything with your byline, Why do I even bother to write?” There seemed little point in trying to be funny, or original, or stylish, or to distill years of experience and acres of reading into 2,000 compressed words as long as Jonathan Gold had access to a keyboard.

The fact that he no longer does is tragic and incomprehensible: diagnosed with pancreatic cancer that the Los Angeles Times reports came at the beginning of this month, then gone in a matter of weeks. But it also seems to be the greatest possible cheat. Now what I think is, Why bother to write when I don’t have your next piece to live up to? He was an endless, and for food writers slightly frustrating, joy to read:

Does it matter that my favorite [taco] stand, set up most evenings in front of an auto body shop, has no name, no license, and may not be there tomorrow or next week? Does the stand’s precariousness, the fact that its lights are powered through cables attached to the battery of a constantly running old car, and the surreptitious nature of the transaction flavor the experience? Or is it the lashings of cumin in the meat’s marinade, the careful grilling and the elegant green salsa that has a family resemblance to a hotly spiced Punjabi chutney?

Or:

Great gelato makers specialize in capturing the ephemeral, the flit of resinous complexity across the midrange of a white peach, the bare hint of sweaty afternoon sex in the scent of a juicy midsummer melon, the phenolic fugue inscribed in the taste of a ripe banana. When you look at a Chardin painting of fruit, the cherries are sweeter, riper, more impossibly aromatic than an actual cherry could ever be. When you taste the cassis sorbet at Paris’s Berthillon, it is more than cassis: rounder, subtler, more exquisitely perfumed than cassis, which in its natural form is a fairly boring kind of black currant. And then there is Bulgarini’s pistachio.

I mean, “the bare hint of sweaty afternoon sex in the scent of a juicy midsummer melon.” You see what I mean.

Gold’s way-too-early death what seems like two weeks after Anthony Bourdain’s marks the loss of two men with the same aim: to bring the world together by learning about and sharing underappreciated foods cooked and consumed by people so deeply woven into the fabric of their communities that the sheer act of downing a dish of, say, cha shiu pork would initiate you into their tribe. They democratized food, and blew out its horizons and what could merit the most discerning attention from the most demanding connoisseurs. They turned the hierarchy of restaurants upside down, and white-tablecloth temples fell to the bottom—worthy of respect and careful attention, certainly, but far less vital than a fugitive taco stand or new gelato cart in front of a Pasadena museum. The difference was that Gold launched his cultural revolution in the mid-’80s, decades before Bourdain filmed his transformational television series.

A UCLA music-history major who spent his high-school years practicing cello behind a closed door, Gold worked after college as a performance artist—mostly naked, he would specify to interviewers—before taking up music criticism for L.A. Weekly and mainstream music magazines. At the Weekly he met Laurie Ochoa, a talented intern who became a gifted editor; as a couple (they married in 1990), they helped bring Los Angeles, the city Gold grew up in and loved beyond measure, into the mainstream of both literary and food consciousness. It was Gold’s fascination with the marginalized interstices of society that informed his appreciation of rap as a music writer, and then his bighearted, citywide exploration and mapping of every hidden purveyor of every kind of food.

Gold was a gracious and avid listener, several streetcars running on parallel tracks in his head at any one time. His typical stance in a group was benign watchfulness; he hesitated before answering a question, then would come forth with a verbal aria. (His music training never left him, and when driving from one end of Los Angeles to the other he would listen to opera in his green Dodge Ram pickup.)

I first discovered Gold through the “Counter Intelligence” columns he wrote for the Weekly while he was still music editor, and they made me aware of the myriad variations of, say, Korean dishes and what they said about the people who cooked and ate them. He made me widen my own definition of food—something he did for generations of aspiring food writers. Our paths would cross at various events and restaurants, but I hung out with the couple most when they moved to New York City so that Ochoa could follow her friend Ruth Reichl to become executive editor of Gourmet, and Gold became the magazine’s New York restaurant critic. Seeing the city through their eyes opened mine: They viewed it as a place of wonderment, both for the parade of endlessly striving humanity and also the deprivation of the vibrant jostling of cultures they loved in their own city, which was clearly the future. So back they went after too short a stay. Their moving together to the same publication was typical: As Pete Wells wrote in his superb tribute in The New York Times, Gold and Ochoa contrived to work together wherever they lived. They were each others’ greatest supporters and readers. They were crazy about about each other.

It was utterly apt that Gold became the first food writer to win a Pulitzer. He wrote miles around the rest of us. But aside from his sui generis, incomparably pungent prose, Gold’s lasting inspiration for all writers is to review restaurants as a way of celebrating and forming community. This was something he did from the time of the “Counter Intelligence” columns on, and a point he brings up again and again in City of Gold, Laura Gabbert’s 2015 documentary about him.

Last year Gold named Locol, a brave and pathbreaking restaurant by Roy Choi and Daniel Patterson in East Watts, which I visited and was greatly impressed by a few days before it opened, the restaurant of the year. The food, designed to mirror and improve on the food available to its neighbors who default to fast food, had come in for criticism because it didn’t live up to some of the standards of the fine-dining founders—though they were deliberately trying to create a new, accessible kind of cuisine. Gold awarded Locol, he said, not just because he happened to love it but because it was a restaurant with a mission. “An ideal candidate [for best restaurant] has delicious food—that’s a given—but also a sense of purpose, a place within its community and the ability to drive the conversation forward,” he wrote of his decision. “It should feel like L.A.”

Jonathan Gold was a writer with a mission: exalting the overlooked. Now it’s up to all of us—Gold couldn’t resist using the second person—to carry it forward.