In the space of nine days in the summer of 1985, film-maker Arthur “Artie” J Bressan Jr made a low budget drama called Buddies. It was a small film, an intimate two-hander that received a muted showing at a handful of cinemas just months after it was completed, a speedy release that was reflective of the urgency behind its conception and rapid shooting schedule.

It has been unavailable ever since, a hushed legacy belying a ground-breaking significance because Buddies is quite possibly the most important film you’ve never heard of.

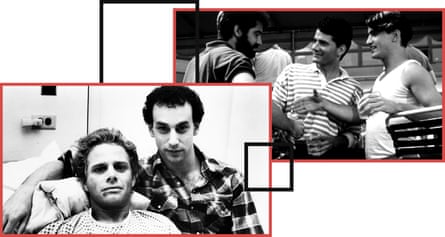

Bressan Jr’s film was the first to ever tackle the Aids pandemic four years after the first clinical diagnosis. It told the story of David, a gay man volunteering as the “buddy” of Robert, dying alone in a hospital bed after being abandoned by his family. The buddy system was a real and regrettably necessary initiative at the time for those in need of support and those involved in the film were making it while witnessing their community crumble around them.

“It was a really bleak time,” David Schachter, who starred in the film as David, says to me in a Manhattan bar, blocks away from where the film was shot. “There was a lot of misinformation and a lot of panic. I was 24, and at that point I didn’t know anyone who’d died. But Artie passed away two years after we made the film and Geoff [Edholm, who played Robert] passed away four years after and life started to imitate art.”

Thirty-three years later, Buddies is receiving a 2K restoration and a theatrical rerelease preceding availability on Blu-ray and DVD for the first time. Its belated recognition given that it pre-dates Philadelphia by almost a decade, the film that brought Aids to the multiplex and the Academy stage, and shines a light on a group of brave performers and film-makers who made a small, often forgotten set of films that served a vital dual purpose.

During his presidency at the height of the crisis, Ronald Reagan was notably silent, having expressed homophobic views during his 1980 campaign trail. (“I will never forgive Reagan and his administration for what he did not do,” Schachter says.) It took the FDA seven long years to approve a pill aimed at combatting the disease, by which time over 25,000 lives in the US had been lost. As well as offering dramatically compelling narratives, these films were also providing visibility to those who felt unseen and unheard by not just the government but also by society at large.

“We were all very much aware of the importance,” says Aidan Quinn, who starred in TV movie An Early Frost which premiered months after Buddies. “You can do some things with the best of intentions and they can fall flat and be flaccid and terrible but this was the opposite.”

Right: John Bolger and Richard Ganoung in Parting Glances. Composite: ITV/REX/Shutterstock/Alamy

Quinn played the role of a young man forced out of the closet after being diagnosed with HIV in a drama which premiered on NBC to 34 million viewers, a mammoth figure that would be unheard of in a modern age of streaming. It helped to humanize a panic for millions, yet panic was also an unavoidable part of the creative process.

“Brandon Tartikoff, the head of NBC at the time, was literally faced with his board as a lot of them were against showing it and didn’t want to make it,” Quinn says. “They lost all the major advertisers. They had to advertise their own shows instead. It was an incredibly brave thing for them to do as there was such a huge battle.”

The network lost an estimated $500,000 as a result.

During production, Quinn tells of a standards and practices team who were sent to oversee, “like an FBI of the network”, to ensure that no same-sex hand-holding or kissing took place in the film. It took him threatening to walk off set for them to relent.

The film went onto win four Emmys with another 10 nominations and Quinn says that its influence continues to endure. “Still, occasionally I’ll get someone grab my hand and say, ‘Thank you for doing that, that allowed my father and mother to accept me as gay,’” he says. “It was very very gratifying to be a part of it.”

At the same time, writer-director Bill Sherwood was keen to make a film that represented the gay New York community he was a part of and on a shoestring budget he made Parting Glances, a lively comedy drama that was revolutionary in its understatement. While focusing on the lives of a middle class gay couple, the film also included a character with Aids, played by a young Steve Buscemi. His illness wasn’t a defining trait of the character or the movie.

“We didn’t push it as ‘come and see a gay movie about Aids’ because who’s going to see a gay movie about Aids?” says lead actor Richard Ganoung. “I believe it’s done with grace, I believe it’s done with humor and it was done in the same way that Bill made the movie, it’s what he knew. It’s all he knew at that time. We didn’t know what we know now.”

Ganoung was a gay actor in his 20s when he signed on and admits that he wasn’t fully aware of the crisis.

“It was very very early,” he says. “This was only 1986 and while people were still ill, it was mysterious to most of us. It didn’t rear its ugly head in my life until after filming when I moved out to Los Angeles and that’s when I was really like ‘Oh my God, this is taking everyone I know.’”

It took the life of Sherwood, whose breakout hit would be his only film (his next project, a second world war drama that attracted the attention of Robert Redford, failed to materialize after he got sick). “Bill’s own HIV status remained unknown to us for a long time,” Ganoung says. “He was a very private person. Unfortunately I only got to talk to him once when he was ill but fortunately, his illness took him quickly and he didn’t have to suffer.”

Parting Glances gained a cult following and for some, its existence was vitally important. A fan once came up to Ganoung to tell him that he was on the verge of suicide but watching a story about other gay men saved his life. “Over the years, so many people have said they’ve used it to show their parents that they’re gay,” he says. “Older men will tell me they saw it with their lovers who aren’t here anymore.”

But there were also some vocal detractors. Ganoung shares a story of an outraged audience member who once got on her feet at a Q&A to say: “The problem I have is that you made it look so normal.” He took it as a compliment.

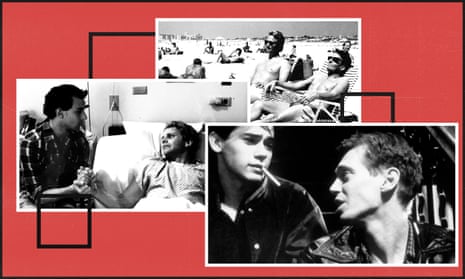

At the end of the 80s, producer Stan Wlodkowski was working on an ensemble drama called Longtime Companion, an indie that would take an ambitiously structured, decade-long approach to covering the illness, starting with the discovery of a small, terrifying New York Times article about a new ‘gay cancer’. It eschewed the freewheeling comedy of Parting Glances for tear-jerking poignancy (Ganoung tells me that after putting it off for years, finally watching it “devastated” him). It also placed Aids at the front and centre, something that made it a tough sell for many.

“We had a cast meeting and came up with names that we wanted,” Wlodkowski says. “We were pretty ambitious and we had some big actors on that list. When I look back now, they just all have strikethroughs through their names because we went after them one after another and really no one was willing to sign on. We struggled.”

Instead, performers who were little-known at the time signed on, including yet-to-breakout stars Dermot Mulroney, Campbell Scott, Mary Louise-Parker and Bruce Davison, while filling positions behind the scenes wasn’t straightforward either.

Right: Stephen Caffrey, Campbell Scott and Dermot Mulroney in Longtime Companion. Composite: Samuel Goldwyn Co/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock/Frameline

The team had their heart set on cinematographer Nester Almendros, whose credits included Sophie’s Choice and Kramer vs Kramer. “I didn’t know that he was HIV positive at the time and he called me back and said he’d just put down the script and would love to do it but he would find himself crying through the lens for the entire movie,” he says. “Then a short time later, he passed away and I made the connection that it would have been too personal for him.”

Other rejections weren’t quite so well-intentioned. A French composer, who Wlodkowski won’t name, was at the top of director Norman René’s wishlist, and without telling him much about it, a copy was sent to Paris. “He watched it right away and called me, saying: ‘I had no idea this was about homosexuals, I do not want to do a movie about them,’” Wlodkowski says. “He’s a very big composer these days. I have a feeling he’s probably, like a lot of people, evolved and become more sympathetic.”

For those involved, there was something both cathartic and frightening about creating art that was directly reflective of the world around them. During production, Wlodkowski was too scared to get tested, as a gay man living in New York, given the hopeless prognosis at the time. “I threw out an address book at one point because there were so many people who had passed away,” he says. “I think I had 22 people in my life that had passed from HIV and I couldn’t bear to look at that book anymore. I just threw it in the garbage.”

During production one day, Wlodkowski went to the hair and makeup trailer for a haircut and the main hairstylist revealed that he was HIV positive and didn’t think he had much longer to live. “He passed away soon after,” he says. “I remember him thanking me for helping put together the movie and that it was really personal to a lot of the crew. I remember that as a moment where I felt as if we’re doing the right thing.”

René also died of complications from Aids six years after the film was released.

Wlodkowski went on to produce a number of big hits, including Now You See Me and Arrival. Ganoung made a handful of films after Parting Glances but is aware of the overwhelming importance of his most recognizable role. “I used to joke and say, ‘I don’t want this on my tombstone: he’s the guy from Parting Glances,’” he says. “But now that I’m going to be turning 60 this summer, if that’s all that’s on my tombstone, I’m blessed.”

After Buddies, Schachter’s acting career turned into something far different, working as a community organizer for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the world’s first Hiv/Aids service organization. He now works at NYU. “Getting that callback just seemed less important to me,” he says.

As the only surviving member of the core trio from the 1985 drama, he has an understandably conflicted view of his luck, mentioning a “survivor’s guilt” but also something stronger. “Artie gave me a unique opportunity to represent something, to be a part of history frankly,” Schachter says. “As I look back on it now, I feel incredible pride to be part of this historical artifact during a very bleak period of time. Artie said he named the character David after me so he would condemn me to good health and I’m grateful for that.”

Buddies will be re-released in the US on 22 June via Frameline Distribution at the Quad cinema in New York with a DVD and Blu-ray release to follow

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion