Trapped in a purgatory of masterplans, consultations and yet more plans, east London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is no stranger to revisions. Proposals for a £1.3bn cultural hub, announced by former mayor Boris Johnson in 2013 and unveiled in 2016, have just been redesigned, rebranded and relaunched by the current mayor, Sadiq Khan, who, in a moment of deja vu, hailed it on Tuesday as “the most ambitious new project of its kind for decades”.

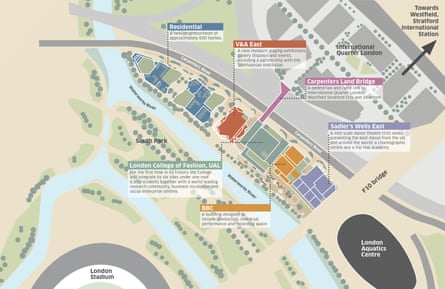

Featuring an outpost of the Victoria and Albert Museum, a Sadler’s Wells dance theatre and a new home for the London College of Fashion, along with residential towers, the park’s planned arts district, once known as Olympicopolis, in tune with Johnson’s penchant for ancient Greek, has been reborn as East Bank, with the addition of a new base for the BBC symphony orchestra and recording studios. It now features four towers rather than two, the V&A has been slashed to a third of its size and what was a parade of dour brick blocks has been jollied up in more expressive clothing.

Its architects say it is now a “more urban” place, a “piece of city” to line the edge of the park rather than a row of individual buildings. It does indeed look like care has been taken with thresholds, undercrofts and open edges that will “enable people to be ‘within’ the buildings without actually entering them”. But why the total rethink?

Successive mayors always want to make their mark, but the main reason for the redesign – which entailed starting from scratch, with a revised budget of £1.1bn – is to be found more than 12 miles west, thanks to a baroque quirk of London’s planning system.

The parkgoers of leafy Richmond might not know their power, but they have been bestowed with the sacred right to an unencumbered view of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, nine miles away, behind which the 47-storey twin towers of the original Olympicopolis plan would have poked up when viewed through a telescope mounted in Richmond park for the purpose. The breach of the protected view was only discovered when the cheeky concrete shaft of one of Stratford’s other towers, Manhattan Loft Gardens, appeared on the skyline at the end of 2016, leering like a middle finger behind St Paul’s, to the horror of conservationists with telephoto lenses.

Despite the view already being despoiled, the London Legacy Development Corporation decided to chop its blocks in half in deference to the protected prospect, making four towers of 23 storeys. As a result, the neighbouring cultural and educational buildings have been forced to shrink and must now huddle together at the end of the site, as if retreating from the incessant march of luxury flats. But are there improvements in the redesign?

“Moving the buildings closer together has created a more dynamic place,” argues architect John Tuomey, one half of the celebrated Dublin practice O’Donnell + Tuomey (ODT), which won the competition to design the cultural quarter in 2015, with Allies and Morrison and Spanish practice Arquitecturia. Bob Allies agrees: “It’s a tougher, richer, more interesting project. And those 40-odd-storey towers did seem a bit weird.”

When the first scheme was unveiled, it was criticised in some quarters as a missed opportunity. “Dull as ditchwater,” was Will Alsop’s verdict, while Peter Cook compared it to the kind of “under-amplified Vivaldi … fed to you in a gift shop”. It was deemed too square and too beige. The pressure to perform has led the architects to indulge in a wider variety of shapes and materials, some of which is welcome, but it feels a little contrived when squeezed on to the newly reduced site, as if trying too hard to give each institution its own identity. After public consultations and multi-headed client input, the result is design by committee.

The V&A, once the star of the show, now looks like a dinky trinket, sandwiched between the bulky fashion college and the blocks of flats. Designed by ODT, it has gone from a shifting stack of brick blocks to a faceted concrete pavilion, with the air of an angular octopus standing on tiptoes. Squeezed for space, its open archive will be relocated across the park in the former Olympic broadcasting centre, reborn as Here East, in a space designed by New York firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro. It has freed up ODT’s building to be pure galleries, wrapped in a pleated concrete skin, where a meandering staircase will take visitors on an intriguing journey up to a roof terrace, with echoes of the architect’s magical brick ziggurat for the London School of Economics. It is small, but potentially perfectly formed.

The London College of Fashion, by Allies and Morrison, is the same size as before, but has ditched its zigzag brick facade in favour of a simple white concrete frame with big factory windows. The chunky columns form a three-storey colonnade around its base, drawing you into an airy world of high-ceilinged studios and wide staircases. The BBC stands next door, by the same architects, as a polite composition of boxes clad in weathering steel and concrete, containing performance space and recording studios, where free events will take place. The lineup is completed with Sadler’s Wells, designed by ODT as a purplish brick shed containing a 550-seat theatre and dance studios. It’s topped with a sawtooth factory roofline, recalling the industrial history of the site. It is a consciously tough edifice to stand opposite the voluptuous curves of Zaha Hadid’s aquatics centre, and a ground-floor corner will be devoted to a community dance space, providing a shop window of cavorting bodies to lure people inside.

“It’s ready to work,” says Sheila O’Donnell. “We didn’t want the building to feel institutional, but to be a creative place where things are being made.” It is a principle that Allies says has informed the approach across the site. In line with the crafted ethos, the materials will all bear the marks of being cast, whether in brick, concrete or ceramic tile, while Arquitecturia has designed a pleasingly fleshy bridge of sculpted pink concrete and steel. Care has been given to the landscaped podium on which the buildings stand, creating a place of cascading terraces, steps and ramps to bring people down to the water’s edge, where performances and events are planned to animate the space.

In this, the design takes a cue from the multi-levelled terraces of the Southbank Centre, from where East Bank draws inspiration for both its mixed functions and its name. It will have a similar cocktail of retail outlets stuffed into its podium, and there is every chance that some of the 50 million people who flock to Westfield each year might be lured across the bridge to inject some South Bank bustle. While both sites were the legacies of international events – the 1951 Festival of Britain and the 2012 Olympic Games – the glaring difference is that East Bank is being conceived in a climate when the sale of private flats is expected to pay for the public bounty; for all the architects’ best intentions, the apartment-to-culture ratio feels painfully imbalanced.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion