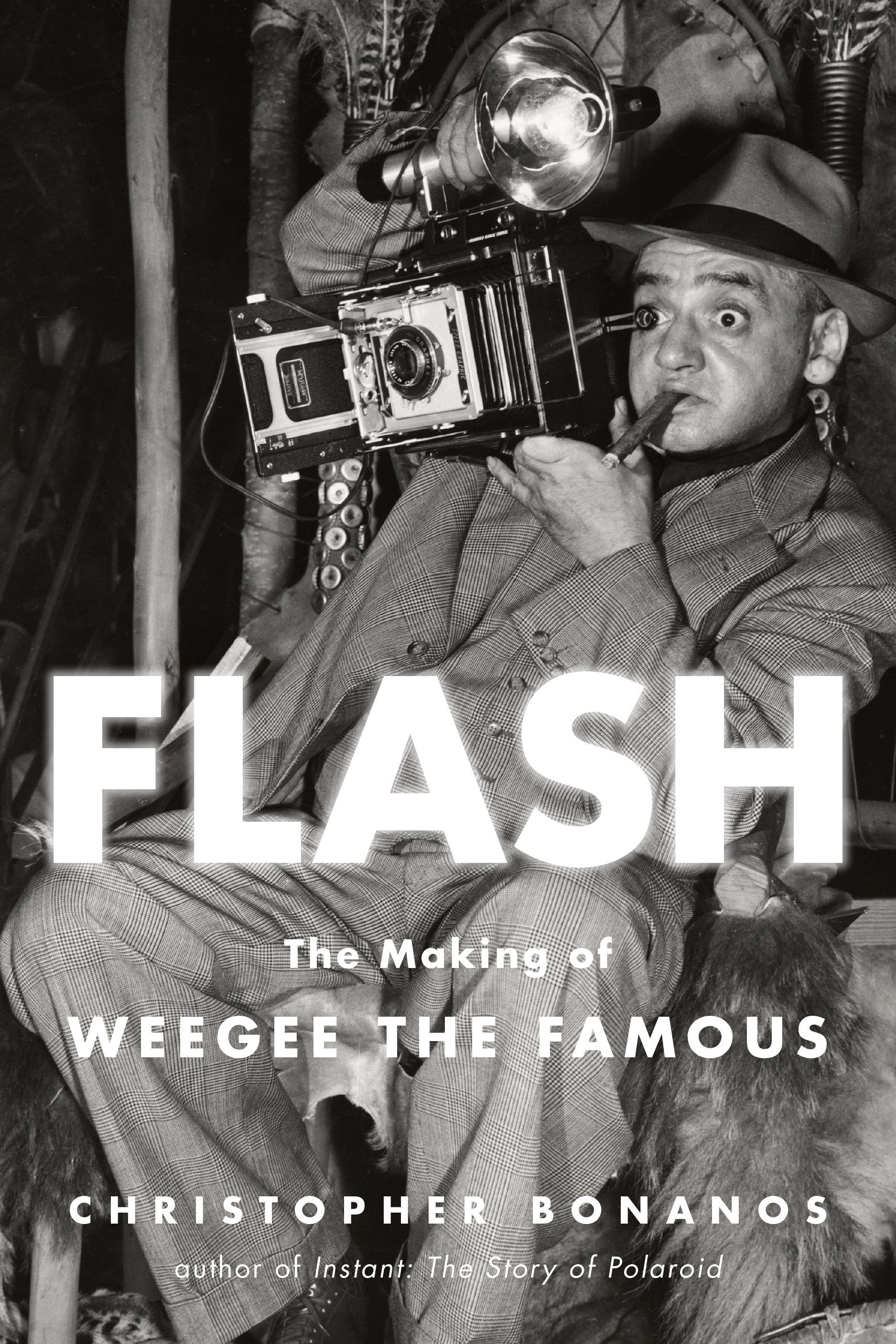

In 1963, Arthur Fellig, the photographer known as Weegee, was past the peak of his career. He had been the most famous press photographer alive in the 1940s, especially after he published his best-selling book Naked City, and had moved on into filmmaking, experimental trick-lens photography, and (trying out) acting. He spent a few years in Hollywood, then returned to New York. Increasingly, though, he was having trouble getting assignments and earning money, and in the late 50s had begun working more often in Europe, where he was still somewhat of a novelty. In 1961 and 1962, he worked on three Z-grade exploitation movies, two of which were set at nudist camps, in which he had a pair of brief walk-on roles and served as photographic consultant. In the third one, directed by a fly-by-night character named Sherman Price, Weegee was the star, with his name not only above the title but in it. The Imp-Probable Mr. Weegee was shot in Paris on a tiny budget, and it’s terrible. Shortly before the end of the shoot, he left Paris, and his last few scenes were shot with a stand-in. Weegee sold the director his hat and overcoat, at a shakedown price, before he took off.

He had good reason to leave on time, though. Whereas Sherman Price occupied the absolute basement of the film world, Weegee’s next project was with a man who was working at its zenith. Stanley Kubrick, coming off the successes of Lolita and Spartacus, had begun the meticulous production of his next movie, a black comedy starring Peter Sellers about a Cold War scenario that goes very wrong. Kubrick was rapidly becoming one of the best-regarded filmmakers in the world, but his early life had been spent with a Speed Graphic in his hand rather than a Bolex. He’d worked as a press photographer from the age of 17, principally for Look magazine, making extraordinarily good photographs that owed some of their look to Weegee’s. He even shot a few with infrared film. The two men had crossed paths regularly—“I knew him around,” Weegee later explained—and Kubrick had been attentive to Weegee’s work and career. As Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb began filming at Shepperton Studios, Kubrick found himself able to, after a fashion, repay the artistic debt, and he hired Weegee to work on the set, taking still pictures—but not the stills that anyone would have made, which were left to Columbia’s in-house photographers.

As Weegee explained:

Stanley says to me, “Look, all the photographers nowadays, they’re using available light,” and so forth. He doesn’t quite like it. He’s a nut on sharp pictures. He says, “Weegee, when you make pictures for Naked City they were very crude. You had the flash bulb right on the camera. This is … If you took pictures like this nowadays they’d laugh at you. But I want it like that.” So you’ll notice I’m the only one that makes flash pictures. I don’t have to actually. But I do it to make Stanley happy.

The production notes do not list Weegee as a set photographer, but there’s a 750-pound fee in the records for an unnamed “technical advisor,” and that’s almost surely Weegee. He loved the experience: Staying at the Mapleton Hotel, he had a luxury car taking him to and from Shepperton every day and free rein on the set. It was supposed to be a one-month residency, but given Kubrick’s slow and madly obsessive work habits and an A-lister’s budget, it was extended to three.

The pictures turned out to be superb. They’re the last truly great body of work Weegee made in his life, a real return to strength. They had that intense caught-in-action strangeness, the otherworldly is-this-real quality that suffused his best nighttime New York photos. And because the principal film set on which he was working was Kubrick’s war room, the backgrounds are nearly black, tailor-made for him. He documented Kubrick in action from every angle: as the director was framing shots, climbing on stepladders, lying on his back with a movie camera in hand, and, in one case, peering through a tiny peephole in a curtain on the set. Once again, the voyeur photographed the watcher—and was there ever a more acutely focused watcher than Stanley Kubrick?

Inadvertently, Weegee also showed the world a part of the film that most of us cannot otherwise see. Dr. Strangelove was meant to end with an enormous slapstick pie fight in the war room, and the scene was filmed as Weegee snapped away, his Rolleiflex sealed in a case built for underwater photography. Everyone, including the photographer, ended up covered in custard. Kubrick later decided that it was too glib a finale for a story about nuclear annihilation, and he rewrote and reshot the ending. The unused scene went into the vaults, and only from Weegee’s pictures can we get a sense of how it looked. (Often said to have been destroyed, the pie-fight footage does exist. It was shown in public once, in 1999, at the National Film Theatre in London.)

Peter Sellers had three roles in the picture, and the scenes in which he played Dr. Strangelove were scheduled toward the end of principal filming. By the time they came around, Sellers had been watching Weegee at work for weeks. He found him fascinating, as anyone obsessed with accents and eccentricities would, and he not only observed Weegee but absorbed him. A few months later, on Steve Allen’s TV show, Allen asked Sellers about Strangelove’s peculiar high-pitched German-accented English, and Sellers told him where the accent came from:

I was stuck, you see, because I didn’t want to do sort of a normal English broken-German-accent thing. So on the set was a little photographer from New York, a very cute little fellow called Weegee—you must’ve heard of him. And he had a little voice, like this, used to [and here Sellers steps into an uncanny impression of Weegee’s voice] walk around the set talking like this most of the time. He’d say, “I’m looking for a girl with a beautiful body and a sick mind!”

And I got an idea, I was really stuck for this … I put a German accent on top of that, and I suddenly got [in Strangelove’s voice] dis thing, you know, where—going up here and … so I got him into Dr. Strangelove. So really it’s Weegee. I don’t know if he knows it.

Of all the Zelig moments in Weegee’s latter years, this has to be the most extraordinary: that his very voice is infused into one of the great tour-de-force performances ever put on screen. Sellers even liked Weegee enough to interview him (judging by a couple of lines in the conversation, it was intended to air on the BBC) around the time filming ended. Sellers was absolutely neutral and laconic, hanging back to let Weegee rush in and fill the pauses. Weegee chattered on about knowing Kubrick as a youngster and told yarns about his recent work at the nudist camp. “Where do you put your filters?” deadpanned Sellers in response. “I don’t use filters!” Weegee cheerily replied, adding that his fellow nudists had granted him special dispensation to carry a little camera case, but that he used it only for his cigars.

From the book Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous by Christopher Bonanos. Copyright © 2018 by Christopher Bonanos. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Co.