Why the Dancing Makes 'This Is America' So Uncomfortable to Watch

The new music video from Childish Gambino weaponizes the viewer’s instinctive bodily empathy.

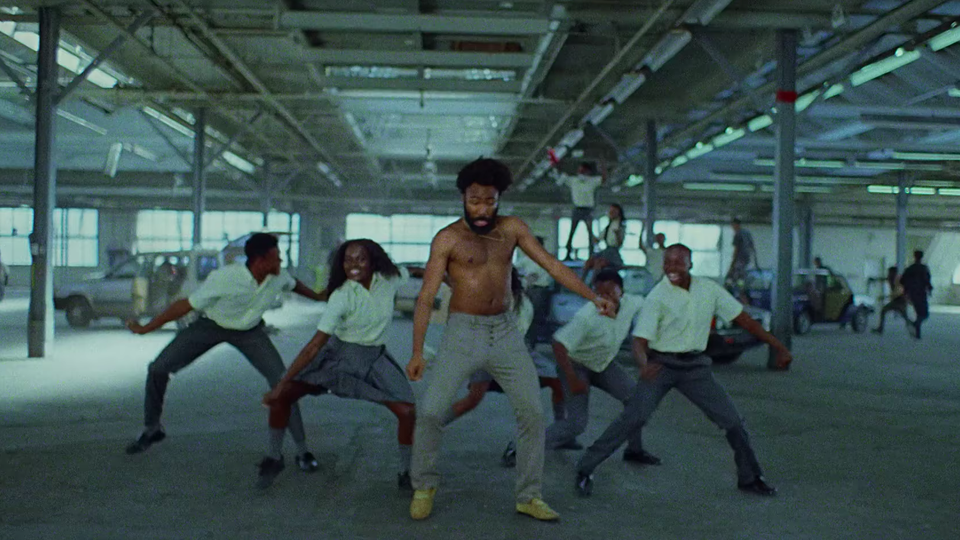

“This Is America” isn’t the first time that Donald Glover, as his musical alter ego Childish Gambino, has harnessed dance in service of surrealism. But the art form has a conspicuous symbolic significance in the artist’s latest single, which Glover debuted on Saturday Night Live: The song’s emphasis on dance was apparent in his live performance on the show, in the cover art for the track, and in the remarkable music video itself, which has more than 36 million views on YouTube as of publication. In the video, a grinning, shirtless Glover dances through a giant warehouse, occasionally accompanied by black school children in uniform, as chaotic scenes of violence unfold behind him—and are sometimes enacted by him.

One popular interpretation is that the short film—directed by Glover’s frequent collaborator Hiro Murai—is a denunciation of the distractions that keep many Americans from noticing how the world around them is falling apart. Those diversions are represented by Glover and the schoolkids’ performances; their choreographed moves include at least 10 different popular dances, such as the shoot and the South African Gwara Gwara. Viral dances tend to be associated with frivolity and vapidity, despite the fact that dancing has always been a communicative art of great cultural significance that spreads joy through movement. Glover, however, subverts an uplifting communal activity to deliver a powerful indictment of the unsettling contradictions in American society.

Though the word viral is so associated with internet-sharing now, the virus-like quality of dance was being analyzed long before the existence of social media. John Martin, one of the first prominent dance critics, described the medium’s effect on its audience as a contagion. He suggested in his book Introduction to the Dance (1939) that when we watch others dance, “we shall cease to be mere spectators and become participants in the movement that is presented to us, and though to all outward appearances we shall be sitting quietly in our chairs, we shall nevertheless be dancing synthetically with all our musculature.”

Decades later, inspired by ’90s research on so-called mirror neurons—cells discovered in the brains of monkeys that react equally when the body performs an action as when it sees the action performed—modern dance theorists such as Ivar Hagendoorn and Susan Leigh Foster applied the idea to humans. Kinesthetic empathy, critics like Foster have argued, is what makes dance feel so infectious—and what prompts the body, upon seeing another body dance, to internally simulate the movement.

If you watch “This Is America” on YouTube, you might stumble on videos of people who recorded their own reactions to it. Many of these viewers sway along with Glover at first, rolling their own shoulders, nodding to the afro folk–inspired melody as the musician twists his bare torso, revealing his own musculature and contorting his body in ways both alluring and disturbing. But the benign nature of that contagion is shattered when the first gunshot rings out 53 seconds in, and with the jarring transition of the melody to dark, pulsing trap. In the reaction videos, mouths fall open, and people are stunned into paralysis. The shooting itself is shocking, but so is that fact that Glover carries on dancing as if nothing happened.

An internal struggle begins in the viewer’s body, which is pulled between joy and horror. Just as the video questions how we can dance when there is pandemonium all around, the audience struggles with whether to continue moving, too, after witnessing such brutality, especially after Glover shoots an entire choir of gospel singers, supposedly in reference to the 2015 murder of nine churchgoers by Dylann Roof in Charleston, South Carolina.

Susan Leigh Foster, in her paper and performed lecture Kinesthetic Empathies and the Politics of Compassion, outlines Martin’s idea that the internal mimicry of movement extends to emotion, which gives dance the ability to transcend class, cultural, and racial barriers. While there’s certainly value in this potential for universalism, “This Is America” complicates the question of empathy (intentionally or otherwise) because of its references to racial trauma and racist violence. Does the video—which foregrounds black suffering—aim to send a single message to all viewers, to all Americans, regardless of race? Some people were especially troubled by the shooting of the choir: If the scene is meant to evoke an atrocity committed by a white terrorist with a specifically anti-black agenda, what does it mean to see a black man re-create it? And to bring the issue back to the video’s use of dance, what does it mean for nonblack viewers to internally simulate movement inspired by black pain?

Because of all the thorny debates it prompts—and because of how much there is to process, both intellectually and emotionally—“This Is America” seems made for repeat watching. But the dancing, too, reveals its power in a second and third viewing. The dramatic irony is pervasive. It even feels like Glover is aware of your presence. His satisfaction that the viewer has been lulled into a false sense of security seems apparent in the languidness with which he pulls out that gun from his waistband, poses, and then shoots the hooded man in the head.

The scientist Vittorio Gallese, who was part of the team of researchers who discovered mirror neurons, describes kinesthetic empathy as “involuntary and automatic.” Therein lies the dilemma for viewers of “This Is America,” who might recoil at the chaos and yet feel a strong impulse to dance anyway. One man, recording his reaction, summed up this tension when he remarked: “I’m lowkey scared of him right now. But I have to bop my head.”

This kind of empathy means viewers cannot, really, just be passive observers. The video’s juxtaposition of carefree dancing with carnage and disorder, the vacillation between the gospel-Afrobeat hybrid and the harsher, sparse rap reflects the discord in the audience’s bodies, our faces perhaps displaying discomfort while our bodies betray us. In doing so, “This Is America” perverts the positive potential of dance’s collective nature, taking it from something celebratory to something far more disturbing that implicates us all.