The sale of seven works by some of America’s best-known 20th-century artists has pushed a Baltimore art museum to the forefront of an international debate as to how the great publicly owned collections can thrive in a rapidly changing world.

Paintings by Andy Warhol, Franz Kline, Kenneth Noland and Jules Olitski will be auctioned at Sotheby’s New York on 16-17 May. A Robert Rauschenberg mural and a second Warhol will be sold separately. It is hoped the “transformative” move will create a “war chest” of $12m (£8.8m) to fund acquisitions of more recent art, with a focus on work by women and artists of colour.

In pushing through the sales, Baltimore Museum of Art’s Scotland-born director Christopher Bedford has squared up to one of the great taboos of the museum world: the disposal – “deaccession”, in art world parlance – of artefacts that are no longer needed or wanted, and could valuably be replaced with something else.

All five artists whose work is up for sale are white and male and have other pieces in the Baltimore collection.

Explaining the move to Artnet, Bedford said: “I don’t think it’s reasonable or appropriate for a museum like the BMA to speak to a city that is 64% black unless we reflect our constituents.”

He added that the sale came at “a historically significant moment … in that the most important artists working today, in my view, are black Americans”.

The massive overrepresentation of white, male artists is a problem the BMA shares with galleries all over the western world, and cuts to the heart of a UK museum heritage that grew out of 19th-century philanthropy, endowments and bequests.

Recent research revealed that female artists account for just 4% of the National Gallery of Scotland’s collection, 20% of the Whitworth Manchester’s and 35% of that held by Tate Modern.

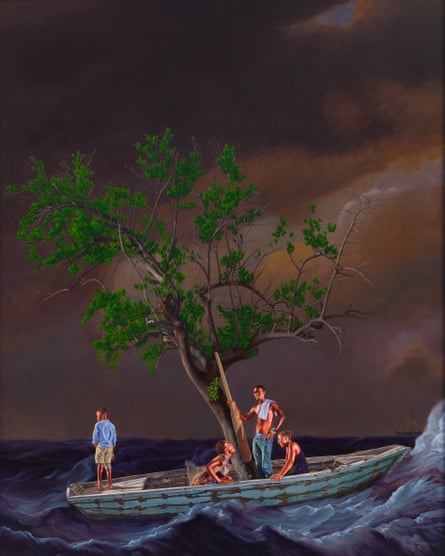

When it comes to BME artists, the picture is even bleaker. Last week, Royal Museums Greenwich announced the acquisition of a painting by Kehinde Wiley, the African American artist who recently made headlines with his portrait of Barack Obama. Ship of Fools – modelled on a picture by Hieronymus Bosch – is the first painting by a known black artist to be bought by the museum, and the first Wiley work to enter a public collection in the UK.

It will form a gang of two with Ship in Bottle, by the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, which went on permanent display outside the Greenwich museum after its stint on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. A bottled replica of Lord Nelson’s ship Victory, it was bought for Greenwich with the help of £264,300 raised through a public appeal.

While most people agree that collections need to be allowed to grow and develop, the question of how – when museum budgets have been slashed in line with other public spending – is an emotive one, as Caroline Douglas, of the Contemporary Art Society, points out.

The CAS was set up in 1910 to help fund public art acquisitions and has a budget of just under £400,000 to spread every year among 70 museums in England, Scotland and Wales. “[Bedford’s] statement about how the museum should represent a community is a conversation I’m having with a lot of museums, about how to speak to their cities,” said Douglas. “Many museums have no acquisitions budgets.”

But she draws the line at deaccessioning. “It’s quite a red line. We give on condition that the museum never sells our gifts. Museums are the forever proposition – that’s why artists want to be in them,” she said. “My view is that we can’t wipe out our history but we need to keep on reflecting society, and use museums as great engines for rethinking that history.”

Stephen Deuchar, of the Art Fund, which gave £40,000 towards the £122,000 cost of Ship of Fools, believes attitudes towards deaccessioning are changing, though it remains a thornier issue in the UK than in the US. “When I started out in the 1980s it was a word you couldn’t even use, but bit by bit that’s been eroded. It’s good that there is a real discussion and it’s now accepted, provided the museum does it in a proper way.”

In part to stimulate that discussion, the Art Fund earlier this year published a report on museum collecting by the historian David Cannadine, which included case studies of good and bad deaccessioning.

On the good side was the Imperial War Museum’s carefully planned sale from 2015 onwards of books, films, weapons and aircraft “where they were not significant to the collection or did not meet the museum’s remit”. On the bad side was the sale of an ancient Egyptian statue by Northampton Museum and Art Gallery to raise money for “key heritage and museum projects”.

Despite an 11th-hour export bar, to enable a UK buyer time to come forward, the statue was released in 2016 to an anonymous buyer, believed to be from the US. As a mark of how seriously such infringements are taken, the museum’s owner, Northampton Borough Council, was stripped of its Arts Council accreditation and banished for five years from membership of the Museums Association.

As Cannadine pointed out in his report, Why Collect?: “Although deaccessioning has ceased to be the taboo subject it largely remained in this country until the end of the 20th century, and has undoubtedly increased since then, most curators would prefer to add to their collections rather than diminish them.”

But despite talk in museum circles about the importance of being dynamic and mobile, “it seems likely that many collections are not managed at all,” he wrote. “A significant proportion of acquisitions do not represent the deliberate and successful implementation of a carefully worked out and discerning policy, but instead result from the acceptance of what are often random gifts and bequests, or from a patriotic determination to ‘save’ for the nation a great work of art that has suddenly and unexpectedly been sent to auction, and which might be ‘lost’ if sold to a buyer from overseas.”

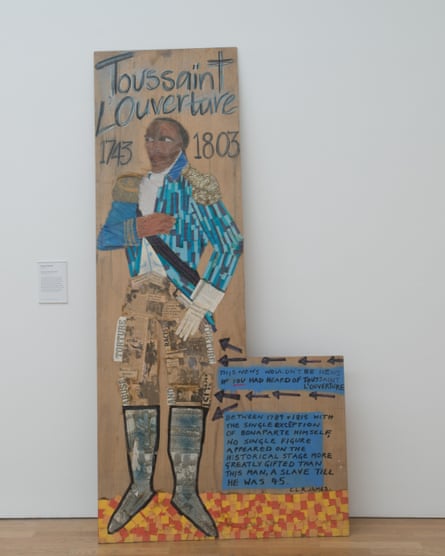

Among those that have taken steps to implement a “discerning policy” are several small regional museums, including the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), whose recent acquisitions include work by black British artists Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce and 2017 Turner prize winner Lubaina Himid.

Mima, which has a collection of art and craft going back to 1900, describes itself as a “useful” museum “with a desire to develop civic agendas that reconnect the museum with its social function, promoting art as a tool for change”.

Senior curator Elinor Morgan said: “Through acquisitions and long-term loans, we are making an effort to feature more historic and local pieces rarely seen in contemporary museums as well as more works by women artists, artists of colour, and those working internationally. In addition, we are challenging conventional models of showing art by mixing chronologies and styles, disciplines and media and histories.”

But when it comes to selling off any of its existing 2,250 art works to fund this mission she is unequivocal. “As a sanctioned museum we cannot deaccession works.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion