The bicentenary of the birth of a Swiss historian might not seem the most glamorous of anniversaries. Unlike his contemporary Karl Marx, also born in 1818, Jacob Burckhardt never inspired any revolutions and doesn’t get his face on T-shirts. Yet some of us are celebrating the 200th birthday of Jacob Burckhardt lavishly. This week a British Academy conference reinterprets his intellectual legacy with contributions from leading international scholars and me, kicking off with a public event tonight at the Warburg Institute.

What’s all the fuss about? Take a look at the names of the Guardian’s online sections: opinion, sport, culture ... why culture? Once upon a time, newspapers used to have arts sections. Today, they’ve caught up – very belatedly – with Burckhardt. The use of the term culture to mean a broad and changing flow of forms from opera to video games may seem like an innovation of the postmodern age, but it actually goes back to Burckhardt’s 1860 book The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy.

Burckhardt invented culture as we know it – not just the official “arts”, but any human activity that has symbolic meaning.

Newspapers and their websites are still behind Burckhardt on this. Looking for articles about fashion and food? You’ll find them in “lifestyle”. Burckhardt saw these too as culture. Of course, so do we – it would just get hard to organise stuff if it was all classed in one big mix. But everyone knows today that clothes are significant cultural creations and that cooking is about meaning as much as flavour. The amazing thing is how clearly Burckhardt saw it 1860.

The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy has not one single chapter dedicated to Renaissance art. It does have, however, a section called Ridicule and Wit. Burckhardt explores every nuance of how people expressed themselves in 15th-century Italy, from cruel jokes to street festivals. In one of his most astonishing insights he even explores how people listened – he shows how sitting through long speeches was a cultural rite in itself. It’s a revelation that makes you think about music and performance in a totally new way. One day, someone will write the history of how we listen today, the cultural history of headphones and podcasts. And that historian will owe everything to Burckhardt.

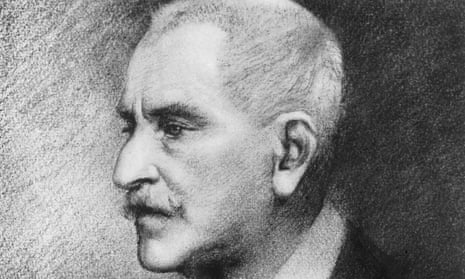

So who was this daring thinker? His portrait on Switzerland’s 1,000-franc note makes him look stern yet sensitive. Born in Basel to a wealthy family and educated in Berlin, where he was taught by the pioneering historian Leopold von Ranke, he doesn’t come across as much of a rebel. Yet Burckhardt’s work is an insidious attack on Germanic nationalism. Writing at a time when Prussia was leading the unification of Germany and pride in Teutonic northern virtues was growing, Burckhardt went out of his way to belittle north European achievements and show that Italy was the true source of European genius.

There is a sensual, amoral intensity to his vision of the Renaissance. He thrills to the ruthless violence of Cesare Borgia, and of Ferrante, ruler of Naples, who according to Burckhardt used to make his guests dine alongside the preserved corpses of his torture victims. It’s the kind of gory detail that makes his masterpiece a still-powerful read. It also widens his notion of culture still further. For Burckhardt, politics and war are cultural forms. He gets this idea from the Renaissance itself – one of his inspirations, Machiavelli, wrote a book called The Art of War.

So perhaps, in his bicentenary, Burckhardt has another, more troubling relevance. Writing when modern European states were being forged, he called his opening chapter The State As a Work of Art. After 1918, it would be dictators who forged a demonic art of mass politics. The Marxist Walter Benjamin accused fascism of “aestheticising” politics. Anyone who has seen Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will knows what he meant.

In 2018 we seem to be living in Burkhardt’s world – and it ain’t pretty. Not only is everything culture, but politics is a mad art form, ruled by symbolic forces and gestures that surge through social media. Are the new populist monsters of politics the descendants of the Renaissance despots who shocked and fascinated Burckhardt?

This quiet scholar’s great book helps us understand our world just as much as the writings of Marx. More so, I fear, in this age when culture Trumps reality.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion