There are three things the internet will seemingly never tire of: cute animals, bad takes, and Disney princesses. The popularity of each of these is rooted in updatability: We enjoy (or suffer through) an inexhaustible supply of adorable critters, an unavoidable string of dubious opinions, and ever-shifting forms of desirable femininity. Twitter illustrated the enduring obsession with the latter last week when the “We need a Disney princess who” meme—which ranged from earnest (“We need a disney princess who’s vegan and fights for animal liberation”) to bizarre (“WE NEED A DISNEY PRINCESS WHO IS LITERALLY SHIA LABEOUF ON PCP”)—reached a flashpoint after a regional Planned Parenthood center’s account tweeted, then deleted, “We need a Disney princess who’s had an abortion.” The outrage from the anti-choice right that followed was understandable enough. But what accounts for the internet’s chronic royal fever?

Spend enough time online, at least in the places I browse, and you’ll inevitably encounter Disney princesses reimagined in any number of fan-art guises. The top Google autocomplete results for “Disney princesses as” are moms, mermaids, sloths, queens, guys, warriors, anime, babies, and the hilarious “lukewarm bowls of water.” (If you like the idea of Disney princesses in container form but want a butcher variation, here they are as cement mixers.) A frighteningly high percentage of Tumblr and DeviantArt’s servers seem to be dedicated to hosting amateur drawings of Disney princesses, where they become online dolls that artists can dress up in different costumes.

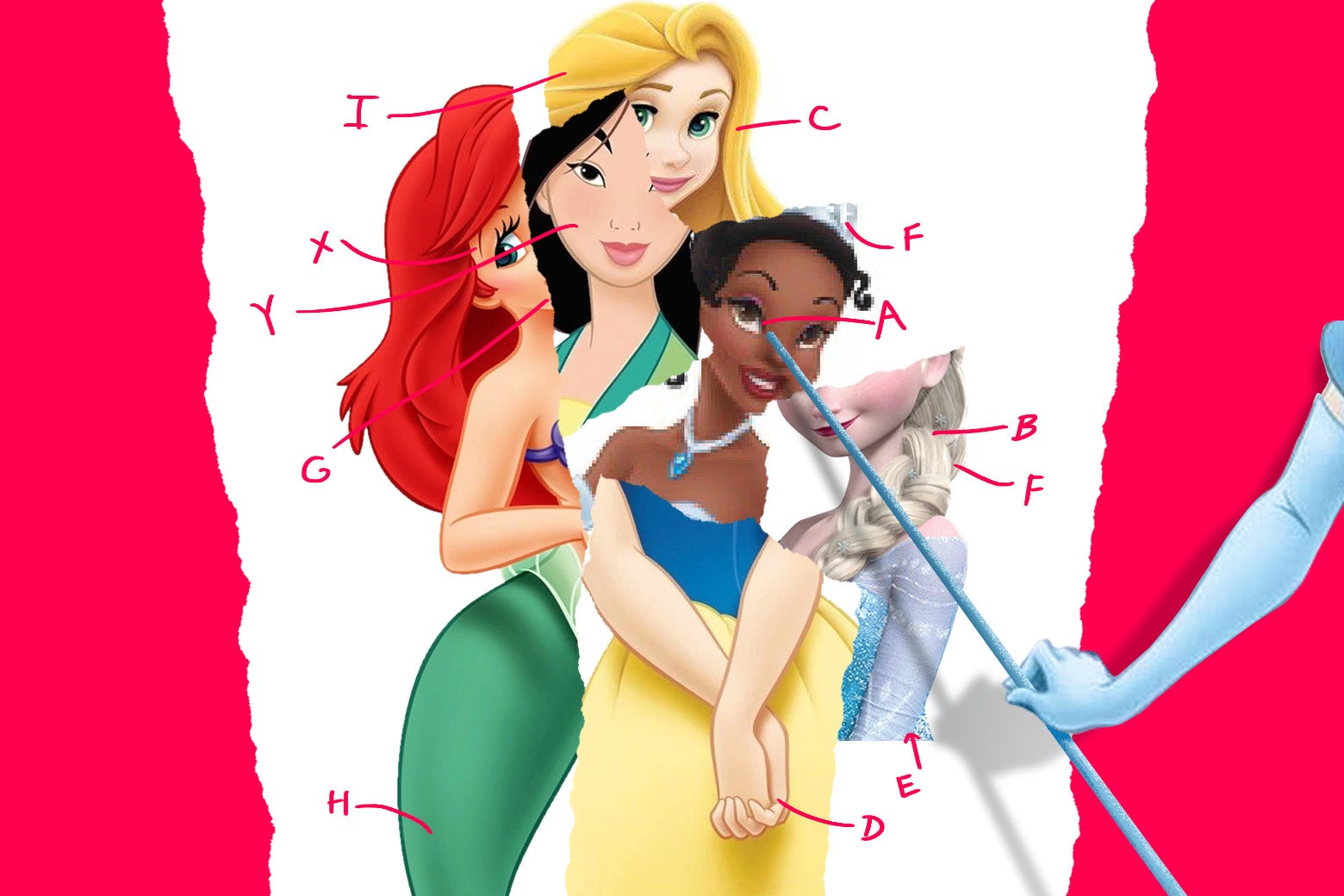

Nostalgia, especially for a monocultural time when most everybody saw Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, certainly contributes to Hipster Ariel’s virality. The adolescent urges to sneer at childhood treasures and dirty up wholesome figures play their role, too. The clickbait industry routinely corrals Disney detritus for reliable traffic, solidifying those listicles as a genre. But an underacknowledged factor in Disney princesses’ longevity may be their ideological messiness. The miscalculated Planned Parenthood tweet also dreamed up a union worker, a trans female, and an undocumented immigrant to join Snow White, Mulan, and Elsa in animated immortality. But modern Disney princesses haven’t aligned politically in one way or another—and it’s likely their contradictions that make them so memorable and appealing.

Once upon a time—around seven years ago—a campaign to portray princess culture as a modern-day scourge reached another (relative) high point. In Cinderella Ate My Daughter, author Peggy Orenstein links the “girlie-girl culture” that Disney princesses represent with a slew of daughterly dangers: “depression, eating disorders, distorted body image, risky sexual behavior.” Feminist critiques have only made further inroads into how we talk about mainstream pop culture since that book’s 2011 publication. The less dogmatic version of feminism embraced by young women today—no less a literary luminary than Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has spoken publicly about her love of makeup—has recast many of these nubile, impossibly waisted emblems of hyperfemininity into rebels and heroines, and convincingly so. Disney princesses signify traditional womanhood and class privilege—and often, the simultaneous refutation of those concepts. No wonder, then, that so many Star Wars fans delighted, after Lucasfilm became another room in the Mouse House, in General Leia’s newfound standing as a Disney princess.

Bookish Belle is widely perceived to be the ’90s Disney renaissance’s most forward-thinking role model. She’d rather read than do anything else, she seems unbothered by her lack of a love life, and she sacrifices her own safety to free her father from the Beast. But her town-weirdo status is softened by her doe eyes and long hair; it’s easier to be a misfit when you’re beautiful (just ask every Winona Ryder character of that era). More pertinently, Belle’s ultimate fate reifies social hierarchy (she’s now with a redeemed hottie, far from that despised provincial life) and in classic Disney princess fashion, teen marriage.

Anyone can love a ’90s Disney princess, including staff members at the Daily Caller—their ideological tangles make them palatable to liberals and conservatives alike. Jasmine’s attractiveness is wrapped up in her royalty but also her wish to be free of the throne’s constraints, like being married off to any neighboring prince. Beloved Nala—yes, not officially a Disney princess, don’t @ me—is characterized by her lovable feistiness, but she mostly exists to aid a brooding dude-lion’s journey. On the other side of the coin, Ariel usually gets dinged for her willingness to basically change the most essential part of herself for a guy, but there’s something admirable about her single-minded focus on getting the hell out of water world. There are anomalies, like Mulan and Merida, who manage to exist outside the compromised feminism of the princess system. But they’re the exceptions that prove the rule.

Admittedly, that broad ideological approach has been in shorter supply in recent years. Two of Disney Animation’s four most recent films, Frozen and Moana, were lauded for rewarding their heroines with something other than a wedding. (The other two, Zootopia and Big Hero 6, were achievements of inclusion, with an interspecies friendship at its heart in the former and an Asian Americanish protagonist who lives in “San Fransokyo” in the latter.) Disney, which has more than a few racially questionable characters in its vault, has become politically self-aware, maybe even woke.

The lean leftward is welcome and long overdue. It’s important for girls and boys to see interesting, progressive female characters, especially in a larger movie landscape where male protagonists outnumber female protagonists 3 to 1, and male characters crowd out female ones at similar levels across children’s entertainment. As flawed as some of their depictions and the movies around them are, Moana, Mulan, Tiana, Pocahontas, and Jasmine remain especially vital for offering images of girls and women of color at the center of their stories.

And yet: We need a Disney princess who … is something else. It’s difficult not to be wary of pleading with Disney, and only Disney, for a broader lineup of princesses, as if the only female characters that matter are the ones that Big Mouse puts out into the world. The more wackadoo “We need a Disney princess” memes rightly mock this unrealistic and corporation-empowering tendency. Disney is already Hollywood’s biggest and most successful studio—and the internet’s ongoing preoccupation with its princesses only strengthens that cultural dominance, ultimately ceding power to a corporation’s judgment of who gets to matter, and who doesn’t. I’ll support a Disney princess “with depression and horrible coping mechanisms,” or one who “drinks four lokos” or “lays eggs in men’s bodies.” But the Disney princess we really need is one who’ll rescue us from Mickey’s iron grip.