How Wild Wild Country Explains Religious Freedom in America

The story of the Oregon cult community—as portrayed in a new Netflix documentary—is key to understanding the current muddled law surrounding the “free exercise of religion.”

My students know that I have based my life on television’s teachings. Hour-length dramas, sci-fi and fantasy shows, and even nighttime teen soap operas (don’t get me started on Buffy the Vampire Slayer) often offer clues to where the nation is heading that don’t show up on news programs until much later.

But in the Trump years, TV drama isn’t much help. None of the “political” shows—House of Cards, Scandal, Homeland, Madam Secretary, etc.—seems to have a handle on what is happening in the United States. But those looking for guideposts in the vast wilderness could do worse than watching Wild Wild Country, the six-part documentary series now streaming on Netflix. The story it tells—of the rise and fall of a cult in the Oregon desert during the 1980s—is fascinating in its own right, brought to life with rare film footage and interviews with the players. Beyond that, the story is key to understanding the current muddled law of “free exercise of religion”—which is the inescapable background to the landmark Supreme Court case of Employment Division v. Smith and its sequel, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

And finally, the story of the Oregon cult community of Rajneeshpuram weirdly foreshadows the nation’s situation in 2018—almost as if a Pacific Northwest Rip Van Winkle had fallen asleep under a Douglas fir three decades ago and dreamed a distorted but prescient nightmare of how American society would in a few decades go off the rails.

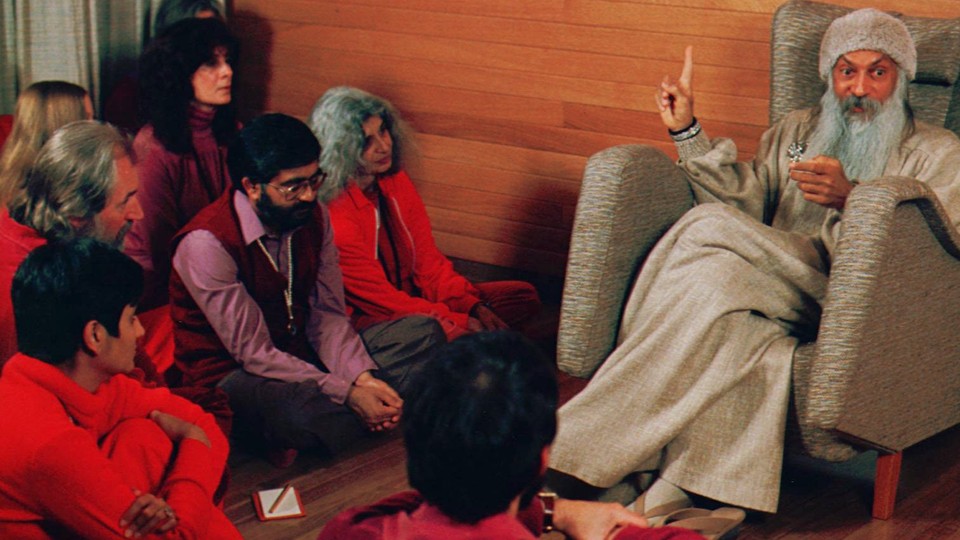

On the first point, I will provide no spoilers, mostly because you wouldn’t believe them. The rise and fall of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his followers is a staggeringly improbable mélange of religion, New Age psychology, land-use and constitutional law, group sex, credit-card scams, xenophobia and immigration terrors, fundamentalism, election fraud, germ warfare, terror bombing, assassination squads, and Putin-style poisoning, all enacted against the haunting background of the Oregon high desert. Viewers will spend the six hours of the film on the edge of their seats, and finish the final episode with a combination of relief—it could have been worse!—and sadness that such an astonishing story is over.

On the second point, the current constitutional doctrine of “free exercise” arises out of the Smith case, which I spent nearly a decade investigating as a professor at the University of Oregon. Smith arose when two men, one Klamath Indian and the other an Anglo, applied to the state for unemployment compensation. Both had been alcohol and drug-abuse counselors at a private social-services agency in Roseburg, Oregon. The Anglo man, Galen Black, attended a tipi ceremony of the Native American Church and ate some of the sacred peyote. When he told his bosses what he had done, he was fired on the spot. Enraged by the insult to Native culture, the second man, a Klamath named Al Smith, defiantly visited a tipi ceremony and took the sacrament. He was fired as well.

The two men applied for unemployment—and the state of Oregon drew an absolute line in the sand. No compensation to “drug” users, it said. The state supreme court ordered it to pay; the state took the case to the Supreme Court. The justices in Washington sent the case back to the state courts; the state supreme court once more told the state to pay. Religious leaders, tribal officials, American Indian activists, and the relatively tolerant Oregon public begged the state to drop the case—but the state’s attorney general, Dave Frohnmayer, insisted on going back to the U.S. Supreme Court.

At this point, without any warning, the high court rewrote the entire law of “free exercise.” From now on, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, that part of the First Amendment provided no protection for religious believers confronting the power of the state. “It may fairly be said that leaving accommodation to the political process will place at a relative disadvantage those religious practices that are not widely engaged in,” Scalia wrote, “but that unavoidable consequence of democratic government must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself or in which judges weigh the social importance of all laws against the centrality of all religious beliefs.”

This aggressive, sloppy, rhadamanthine decision stirred alarm among the whole religious community. A coalition of religious groups formed to reverse the result. Its first act was to exclude peyote religion from the coalition’s ranks, signaling Congress that only respectable religions deserved protection; the group then successfully pressed for passage of RFRA, and state “little RFRAs” as well. It was the federal RFRA which the current Court’s conservative majority used to hold that the Hobby Lobby corporation could cite their stockholders’ religion to opt out of the contraceptive-coverage requirement of the Affordable Care Act. It is in many cases state RFRAs that are being employed to limit the rights of LGBT people and same-sex married couples.

Smith’s landmark status is a persistent puzzle, because most people can’t quite understand why the state of Oregon chose this particular hill to die on. Why did Oregon insist on making such terrible law? The story of Rajneeshpuram sheds some light. As the Oregon cult descended into madness, terrorism, and mass poisoning during the early 1980s, its leaders publicly repeated one refrain American society in 2018 hears often: We are sincere followers of a harmless minority religion. We are being persecuted for our beliefs. The state and local authorities are bigots. The Constitution is our shield.

By the time the last Rajneesh death squad had been rounded up, I suspect, religious-freedom claims had worn rather thin among state officials—some of whom had been targets of the assassination plot. And by ill luck, it was at precisely this moment that Galen Black and Al Smith filed what was a genuinely harmless, entirely deserving unemployment claim. The state’s response was—to quote Ken Kesey’s great Oregon novel, Sometimes a Great Notion—“never give an inch!” Oregon would never tolerate religious claims by “drug users.” It wasn’t the money, it was the principle. No compromise. No discussion. No religious exemptions.

And here the nation is in 2018, with religious freedom brushfires burning all across the landscape.

Finally, the themes of the late-20th-century Rajneesh story are, in scrambled form, the themes of America’s increasingly unhinged 21st-century national dialogue. Rajneesh and many of his followers were immigrants; they insisted that their religious faith should provide them immunity from both land-use laws, immigration rules, fraud claims, and Establishment Clause guarantees. The internal structure of the cult was totalitarian, degenerating into a deadly Lord of the Flies power struggle, in which no one knew from week to week which followers of the leader were in and which were out. The townsfolk who opposed the cultists seem, to contemporary eyes, to have sprung directly out of one of the “Trump voters tell us yet again one more time why they voted for Trump” articles in major media; the cult’s takeover of the tiny town of Antelope, changing its name and harassing longtime residents with a new armed “Rajneesh Peace Force,” embodies the fear of many white Americans about their future as a minority in “their own country.” The cult’s defensiveness was sparked by a genuine terror bombing (carried out, though the film doesn’t make this clear, by an American-born convert to Islam, apparently enraged because of the cult’s Hindu roots). Like Bundy Brothers in orange robes, they then armed themselves with assault rifles and threatened violent resistance to the law.

It doesn’t map precisely, but in the story told by Wild Wild Country, to use a line from W.H. Auden, “the menacing shapes of our fever are precise and alive.”

The Oregon episode ended without mass death or civil conflict. Americans in 2018 can only hope the current nightmare will do the same.