“This is where I paint, this is where I entertain, this is where I sleep,” artist Beverly Brodsky said as she made a sweeping gesture with her arm, encompassing her small Hudson River-adjacent apartment on Bethune Street, in Manhattan’s West Village. Indeed, her large abstract canvases were stacked five to seven deep against the far wall, “and there’s more under my bed, too,” she laughed.

She’s not bothered by the tight quarters, though, since as a long-time painter and art teacher—professions not typically known for sizable salaries—she’d be hard-pressed to find anything in her price range in this area, especially with an unfettered view of the river.

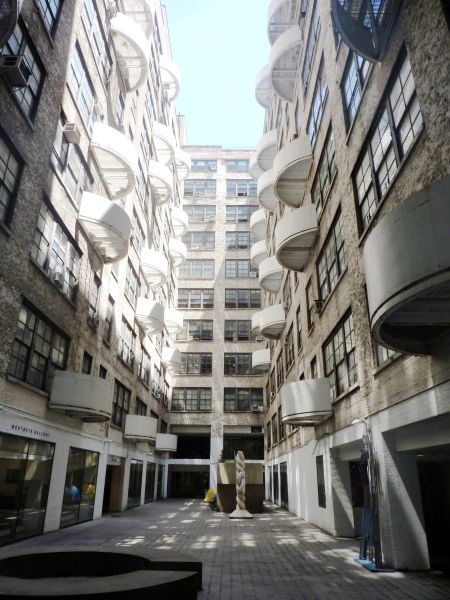

Brodsky is one of the 384 residents in Westbeth, an affordable live-work complex for artists, notable for not only being located in the historic Bell Labs complex—where major modern technologies like TV and radar were invented—but also the first and largest federally subsidized artist colony in the U.S.

Created in the for 1960s as an affordable housing project, Westbeth brought together icons such as Diane Arbus, Robert De Niro Sr. and Benny Andrews. Merce Cunningham headquartered his dance company in a cavernous space in the building in 1971. Once verified as a working artist—meaning a person derived a significant portion of his or her income from the production and sale of their work—residents were admitted by disciplinary committees ranging from music and performance to visual arts and writing. Rent was determined by income.

But what was meant to be a short-term solution for looking to build their careers quickly became a stronghold for artists as the city’s real estate prices rose throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

“For the first 10 years it was pretty come and go,” said Sandra Caplan, who has lived in Westbeth with her husband and fellow painter Ray Ciarrocchi since it was opened as a residential building in 1970. “It was supposed to be a temporary thing—artists would stay for five years or so, just while they were getting their careers going, then move on.” But no one wanted to leave, and there were no bylaws outlined that could make them. By the 1980s, the average wait-time for a unit was 10 to 15 years.

“There are still quite a few residents who are original to the development, about 60 percent or so,” Westbeth board member Don Sutton told Observer. Because there’s been so little turnover, the average age of Westbeth’s residents has substantially increased, with many now in their 70s and 80s, turning the establishment into a kind of de facto retirement community. In fact, a grant-subsidized geriatric social worker is even on hand several days a week.

That doesn’t mean Westbeth residents haven’t seen their fair share of change in the neighborhood, even if their immediate neighbors have largely stayed the same.

“Hookers on the streets, bodies in the river, fires on the piers. Remember that?” Ciarrocchi laughed, looking to his wife who nodded in agreement. “You had to create community here because there was no community here. It was a kind of a socialist mindset.”

Previously the couple had lived in a Chelsea loft that only had a potbelly stove and a toilet. “All we had was a potbelly stove, no shower. Drug addicts would fall asleep in the doorways and I’d have to push them out-of-the-way to go to work every morning,” Caplan said.

“It’s a great New York story, all and romantic and bohemian now, but it was rough back then,” Ciarrocchi noted.

They moved briefly to the Upper West Side, but found it too expensive after they had a baby, which prompted them to apply to Westbeth. But it didn’t offer much more in terms of child support according to Maya Ciarrocchi, Caplan and Ciarrocchi’s daughter, who grew up in the housing project. “There was nothing for children. No preschools. No day care. The kids would run through the halls; they were wild,” she said.

But that, too, has changed, as witnessed first hand by Cirarrocchi, now a working artist herself, and an independent resident of Westbeth from 1997 to 2015. “Now there’s all sorts of schools around here. There’s a private preschool around the corner that is $40,000 a year. It’s certainly not the same neighborhood I was raised in.”

Indeed, the West Village now boasts some of the priciest real estate in the nation. When Caplan and Ciarrocchi moved in, the average New York City apartment was going for $45 per square foot, or roughly $335 for an average space. Now the median square foot is going for about $2,000. While property values were well on the rise as early as the 1980s, Ciarrocchi said the shift in the neighborhood community became palpable in the new millennium. “It all began to change after 9/11, it was really a free for all around here,” he said.

A scramble for property in the neighborhood ensued in the early aughts as money poured into to rebuild the city and nothing had been landmarked west of Washington Street. Richard Meier—the architect behind Westbeth’s redesign a few decades previously—built his hotly contested glass towers on Perry Street and “all of a sudden the designer architects swooped in, and movie stars moved in—Hollywood on the Hudson, they started calling it,” Ciarrocchi recalled. Luckily, Westbeth was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009 and was then given landmark status two years later, meaning the buildings can’t be torn down or altered without the commission’s approval.

The need for affordable housing is only growing in Manhattan, especially as skyrocketing rents continue to displace thousands of low-income earners like artists, and as aging artists, who are unable to produce as much work or teach full-time, occupy some of the city’s most vital spaces. “We’re definitely still painting,” said Caplan, joking that, “you have more time to do it as you get older, but it takes twice as long to finish anything.”

Broadsky, who continues to teach painting at the New School several days a week, said being central in the city is important to the sustainability of her career since she feels a responsibility to stay up to date on what’s going on in the art world for her students. Getting around isn’t as easy as it used to be. Were she to move, “I wouldn’t be able to get back and forth to the museums and galleries as much,” she said. “Right now I can walk to school, too, which is a huge benefit,” one that helps her keep a fuller teaching schedule and better paycheck.

Although the waiting list for Westbeth has been closed since 2006, the board has plans to reopen it in the near future. “We’re trying to find ways to ensure more applicants can get in on an alternating basis and we ultimately want to be more inclusive so that our resident population reflects more accurately that of the city itself,” Sutton said, noting that they have by working with outside organizations, such as the Harlem Arts Alliance and another housing facility in the Bronx with a long waiting list, to build a more diverse and thriving community. “Westbeth was formative in the development of the West Village. It’s a cultural resource as much as it is housing project.”

But as growing wealth disparity continues to shape the city and areas like the West Village in particular, will cheaper rent be enough to offset the income stratification for a second generation of artists? Now living in the Bronx in order to afford a space that can accommodate herself, her partner, and her studio practice, Maya Ciarrocchi has her doubts.

“The last few years I was living at Westbeth, I started to feel this weird shame about being not wealthy while being surrounded by extreme wealth,” she said. Is the neighborhood surrounding the building now a deterrent for artists in search of a thriving creative community in which to base themselves?

Ciarrocchi believes her native neighborhood has become a transient space for “people with pied-a-terre properties,” and recalls finding herself routinely the only one at the nearby D’Agostino’s doing her own grocery shopping, awash in a sea of personal shoppers.“What Westbeth offered was not just cheap rent, but also a creative community in which artists could grow. I think this area has actually lost that sense of community.”