In 1968, The Graduate was nominated for seven Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography, and Best Director. The film would go on to clinch the Best Director Oscar for Mike Nichols, launch the career of Dustin Hoffman, and stir nationwide controversy for its transgressive plot: 21-year-old Benjamin Braddock returns home from college, struggles to find direction, and is seduced by a woman who is twice his age—Mrs. Robinson, the wife of his father’s business partner, played to critical acclaim by Anne Bancroft. Their lust-based affair is cut short when Ben falls in love with Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, Elaine, sparking an intractable conflict between the determined young man and his elders.

Discussing the now-classic motion picture 50 years after its win at the Oscars are Conor Friedersdorf, Adrienne LaFrance, Megan Garber, and Christopher Orr.

Friedersdorf: When I saw The Graduate at 20 or 21 it immediately became one of my favorite movies—I’d soon finish college; I hadn’t the foggiest notion of what I’d do next; and I could easily imagine myself like Ben in the opening scene: overwhelmed by a welcome home party; escaping to my childhood bedroom; wracked with anxiety about how to pursue a meaningful life. What did I want? Like Ben, I couldn’t have said, save that it wasn’t anything among my options, or that I could name … just a feeling. I too wanted my future to be … “different.”

All these years later, reading reviews of The Graduate for The Atlantic’s year-long retrospective on 1968, I was struck by how many critics emphasized something I was oblivious to on my first, second, and third viewings in college: the theme of 1960s generational conflict. Take Roger Ebert. Back then, he savaged the milieu of Ben’s parents as “ferociously stupid,” complaining that his family and their friends “demand that he perform in the role of Successful Young Upward-Venturing Clean-Cut All-American College Grad” and pronouncing Ben “so painfully awkward and ethical that we are forced to admit we would act pretty much as he does, even in his most extreme moments.”

Thirty years later, when Ebert returned to the film, his allegiances had changed:

Well, here *is* to you, Mrs. Robinson: You’ve survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in The Graduate. How could I ever have thought otherwise? What murky generational politics were distorting my view the first time I saw this film? Watching the 30th anniversary revival of The Graduate is like looking at photos of yourself at an old fraternity dance. You’re gawky and your hair is plastered down with Brylcreem, and your date looks as if you found her behind the counter at the Dairy Queen. But—who’s the babe in the corner? The great-looking brunette with the wide-set eyes and the full lips and the knockout figure? Hey, it’s the chaperone!

Great movies remain themselves over the generations; they retain a serene sense of their own identity. Lesser movies are captives of their time. They get dated and lose their original focus and power.

The Graduate (I can see clearly now) is a lesser movie.

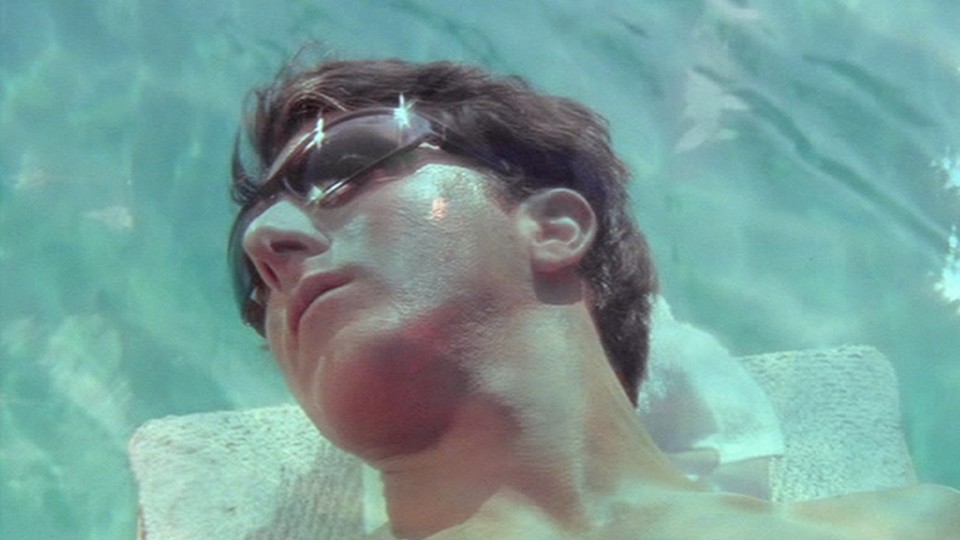

It comes out of a specific time in the late 1960s when parents stood for stodgy middle-class values, and “the kids” were joyous rebels at the cutting edge of the sexual and political revolutions. Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), the clueless hero of The Graduate, was swept in on that wave of feeling, even though it is clear today that he was utterly unaware of his generation and existed outside time and space (he seems most at home at the bottom of a swimming pool).

Today, I’m closer in age to Mrs. Robinson than to Ben. And I’d be revising my opinion of the movie, too, had I thought, on original viewing, that Ben struck a righteous blow on behalf of the younger generation. (Or, if I’d imagined, as the New Republic’s bygone critic did, that “what is truly daring, and therefore refreshing, is the film’s moral stance. Its acceptance of the fact that a young man might have an affair with a woman and still marry her daughter—a situation not exactly unheard of in America although not previously seen in American films—is part of the film’s fundamental insistence: that life, today, in our world, is not worth living unless one can prove it day-by-day, by values that ring true day-by-day.”)

But I wasn’t alienated from my parents or the values of their generation circa 2000; I sympathized with the taboo that would prevent someone from having an affair with a mother then dating her daughter; and I never thought Ben’s parents were anything worse than mildly annoying and a bit blind to their son’s anxieties. (And didn’t they keep advising Ben that he should date Elaine from the start?)

The movie remains a masterpiece, to me, because it captures the existential anxieties of both Ben and Mrs. Robinson, even if the youngish viewer may only appreciate the former’s perspective, and see the movie anew only after reaching the age when one realizes that one’s parents and their friends are people, too.

Orr: It’s funny that you cite those Ebert reviews, Conor. I remember them well, having read the latter years ago and then gone back to read the former. I thought his about-face wildly wrongheaded then and, if anything, even more so now.

What made Ebert such a great critic was that at his core he was an enthusiast, and this is a case where I think his enthusiasms got the better of him, in both directions. It’s obviously not The Graduate that underwent a change in identity between Ebert’s early and late opinions of it; it’s Ebert who did. If anything, his radical reevaluation of the movie speaks to how well it captured its generational divide: Ebert adored it when he was on the “right” side of the divide and reviled it once he reached the “wrong” one.

Like you, I didn’t see the film until college (I was 1 year old when it was released), and like you, it did not speak to me so personally that I felt any obligation to pick sides. It was not a vibrant, political cry, but already an acknowledged “classic,” tamed and domesticated by the passage of years. Nonetheless, rewatching it recently I was struck by the degree to which it is an almost perfect document of its moment—a moment that felt to many like a cultural “hinge” between a dreary present that was merely a monotonous continuation of the past, and an unknown future that, whatever it might contain, had to be better.

Nearly every scene in the film—nearly every line—makes this case in one form or another. In the opening party scene, there’s the line you cite about Ben wanting his “future” to be “different,” followed almost immediately by Mr. McGuire’s recommendation that there’s a great “future” in plastics. In the next scene, at the Robinsons’, Ben twice more expresses concern about his “future.” The older characters, by contrast, don’t seem to have any future ahead of them at all. Mr. Robinson laments that he’d like to be Ben’s age again, before vicariously recommending that Ben “sow a few wild oats.” Mrs. Robinson, of course, goes further, essentially living out her husband’s fantasy of youthful indiscretion.

Throughout the film, the adults around Ben have an almost vampiric attachment to him, as if they can regain their own youth by stealing his. Mrs. Robinson takes this to the greatest extreme, but it recurs repeatedly in lesser forms.

Ben’s parents use him essentially as a party favor on not one but two occasions (his homecoming and his fish-in-a-bowl 21st birthday party), and they exhibit an unhealthy obsession with getting Ben to date the daughter of his dad’s business partner. When Ben arrives at the Taft Hotel for his first assignation with Mrs. Robinson, he is met with an outflux of elderly guests. It’s as if by entering the building he is crossing the threshold not merely into adulthood but into middle age.

And I very much doubt that it is a coincidence that the montage set to “The Sound of Silence” and “April Come She Will” ends with the line, “A love once new has now grown old.”

As the movie progresses, the theme of generational warfare only becomes more conspicuous. In the middle of their tryst, Mrs. Robinson tells Ben, “I just don’t think we have much to say to each other.” He in turn calls her “a broken-down alcoholic.” Ben, who drives a trim and modern little Alfa Romeo, openly mocks the idea that Elaine was conceived in a Ford—literally, the oldest make of mass-produced car in existence. When Mrs. Robinson forbids Ben from taking out Elaine she is, for all intents and purposes, trying to prevent him from returning to his youthful tribe and keep him trapped in this simulacrum of middle age.

And when Ben does take Elaine out, it’s little wonder that he tells her she’s “the first person I could stand to be with.” She is literally the only person his own age that we have seen up to this point in the entire film. Ben appears to have no friends or contemporaries of any kind. He’s like Charlton Heston, but rather than apes he’s found himself trapped on the Planet of the Old People.

I think the movie starts to fall apart as soon as Ben follows Elaine to Berkeley. It loses focus and plausibility—can any human being actually be as passive as Elaine?—and plays almost like a wish-fulfillment dream sequence that Ben will eventually wake up from, a la Brazil. (It is, as Ben himself notes, “completely baked.”)

But the theme of generational conflict continues. His middle-aged landlord (Norman Fell!) wants him out, because “I don’t like you.” Mr. Robinson asks if Ben despises him or “just the things I stand for.” Even Ben’s romantic rival, Carl Smith, though theoretically of the same generation, is presented as prematurely aged. Who brings a pipe to the zoo? I think the proper answer is no one. But if anyone did, they would almost certainly be old. When Elaine tells Ben that Carl proposed to her, he replies, “He didn’t get down on his knees, I hope?” as if that would be the squarest, most old-fashioned gesture imaginable.

In the end, of course, Ben rescues Elaine from the premature old age that Carl represents. (Note, again, that apart from bride and groom there appear to be virtually no young folk at the wedding—Elaine is essentially marrying into the Planet of the Old People.) Elaine flees the altar, despite having already married Carl, and she and Ben hop a bus to get out of there. (Whatever else you may think of it, that’s certainly not square or old-fashioned.) Which leads to the most crucial scene of the movie, and the one that I think puts the lie to Ebert’s latter-day assessment. As the bus pulls away to “The Sound of Silence,” it finally dawns on Ben and Elaine that they have absolutely no idea what this future they’ve been clawing toward might hold for them. (Anyone who remembers the ’70s will recall that the decade was on no level paradise.) The new, highly dubious couple is, belatedly if appropriately, terrified. Loathing the present is a far cry from having any idea how to build a better future.

LaFrance: I can’t believe I never noticed there are no young people at the wedding! I love The Graduate. It is, to me, a perfect film. No shot is wasted. Every moment is deliberate. The “Sound of Silence/April Come She Will” montage still amazes me—not just the clever cinematography, but also because of how it condenses all of the film’s tension into four Oedipal minutes, all without dialogue.

One thing that’s always perplexed me about the film, though, has to do with the generational divide that you both mentioned. The film is set in the late 1960s, and the soundtrack is decidedly of that moment, but everything else about it feels stuck in the late 1950s. There is no mention of Vietnam—barely an allusion to it, other than Simon and Garfunkel’s lyrics. There is no pot-smoking or protesting. Benjamin Braddock is clean-cut and clean shaven—we actually see him shaving in multiple scenes. He often wears a tie. Even the drive-up hamburger joint where Benjamin and Elaine go after their first date has a decidedly Tab Hunter vibe to it. And when the kids parked in the car next to Benjamin’s (forever-dreamy) Alfa Romeo start blasting “The Big Bright Green Pleasure Machine,” Benjamin leans over and asks them to turn down the volume.

Maybe all this is by design. The moment at the burger stand underscores how Benjamin was already hopeless against any effort to avoid turning out just like his cocktail-generation parents. He’s just as phony as they are. Besides, a moviegoer in 1967 wouldn’t have needed a reminder of the war, or of the extent to which it fueled resentment among the Baby Boomers being drafted at the time. I don’t quite understand how young audiences would have seen Benjamin’s stupefaction in the face of a future beyond his control as righteous—or even particularly rebellious. There’s really nothing countercultural about running off with the pretty girl next door.

Orr: You’ve inspired me to offer a super-quick response, Adrienne. In my entry, I’d considered throwing in a few lines about Rebel Without a Cause, another of the defining examples of the American generational-conflict subgenre. (It’s even set, like The Graduate, in L.A. County.) But it didn’t occur to me that, among their many similarities, the two movies seem to catalogue a similar generational divide, despite the fact that Rebel was released 12 years earlier—and 12 years that, given what was happening in the country at the time, might as well have been 25. (The Charles Webb novel that The Graduate was based on was written in 1963, but still.)

I’d honestly never given much thought to the way that The Graduate is simultaneously of its moment and seemingly from another decade altogether. Even the Simon and Garfunkel soundtrack, while technically mid-to-late 60s, is really a form of throwback music. One of their principal influences was the Everly Brothers; the two duos even toured together in the early 2000s. As noted, I was (literally) a baby in 1968, but it’s hard to think of a less rebellious, more “square” choice of contemporaneous musical accompaniment than old Paul and Art.

Garber: Those are such good points—I’d never considered how out-of-its-time The Graduate is. And I think one generous reading of the ’50s/’60s thing—generous to The Graduate itself—is one that sees the decade discrepancy serving the other theme you three were discussing: the generational tensions at play. The way young people and older people can have of talking past each other, of willfully misunderstanding each other, even of battling each other—a dynamic the movie so deftly captures.

One of the things I appreciate about The Graduate is how horribly hermetic Nichols et al. managed to make its universe (that universe being, like you said, Chris, L.A.—traditionally a place of sunniness and breeziness and fantasy and possibility). Here, though, L.A. is stifling. That plane. That pool. That fish tank. That diving suit, with its ridiculous flippers smacking awkwardly on the kitchen floor. There’s so much visual emphasis on doors, here, too … doors open, but, much more often, doors shut. Possibilities foreclosed.

And—here’s, maybe, a connection to the film’s (lack of) overt political context you were discussing—that sense of thwarted potential nicely emphasizes Ben’s (and, really, pretty much all the other characters’) extreme myopia: their inability to see, or really to care, beyond themselves. A self-absorption that is so all-encompassing that it never occurs to anyone involved to question or attempt to correct it.

So, in that sense, maybe it’s fitting that there’s no war in this movie. Or, for that matter, a civil-rights struggle, or a women’s movement, or political strife of any kind. Those absences could definitely be an oversight, but they could also be part of the point: In a movie about people who are as thoroughly selfish as these characters are—a movie that is about stifled people as much as it’s about stifled dreams—the broader world has no place. This universe is small, and solipsism reigns.

But! That’s, like I said, the generous reading of things. And I’m not actually sure that I’m fully convinced by it. Because, overall, I’m with Roger Ebert: I largely disliked The Graduate on rewatching it. Which isn’t to say that I didn’t appreciate it, still (I completely agree, Adrienne, there is some amazing filmmaking in it), but it is to say that it frustrated me and angered me and left me, in the end, cold.

Chris, you mentioned how the movie falls apart in its second half, and I so deeply agree. As far as I’m concerned that’s in large part because its plot hangs so insistently on the motivations of one Elaine Robinson. And those motivations … make no sense at all. Like, truly, none. She goes on one horrible-and-insulting-but-then-better-because-burgers(?) date with Ben; she thinks (or maybe allows herself to believe) that Ben raped her mother; she realizes the full truth; she comes back to him anyway. He asks her to marry him; she initially says no; he is legitimately surprised that she won’t acquiesce to him. I realize this is the era of the feminine mystique, and that Ben might represent to Elaine the very strain of rebelliousness that her mother represented to Ben … but that’s another generous reading, because the film treats Elaine, for the most part, as an eyelash-batting plot device. “I know what I’m doing is the best thing for you,” Elaine writes to Ben in a note about her future, and: sigh.

I could definitely be missing something. Maybe, sure, all the absurdity is the point. The New York Times review, from late 1967, called The Graduate “one of the best seriocomic social satires we’ve had from Hollywood since Preston Sturges was making them.” Maybe my sense of satire has been so thoroughly calibrated to 2018 standards that I can no longer appreciate the strain of “seriocomedy” Elaine’s character arc represents. Maaaaaaaybe The Graduate is a kind of pre–Breaking Bad Breaking Bad: a good guy slowly transformed into an agent of chaos, the transformation propelled not by financial need, but by its opposite. Maybe we’re watching Ben’s descent into conformity/rebellion/an exciting future in plastics. Maybe we’re seeing the makings of the “me decade,” festering in the L.A. sun. Maybe Elaine’s baffling passivity is a work of sly feminism. Maybe?

Still, though: Team Ebert.

Because, watching The Graduate in 2018, I was not at all convinced that the film is self-aware enough to know what it’s mocking, and for that matter what it’s endorsing (besides, evidently, the work of Simon and Garfunkel). The movie seems, itself, thoroughly Team Ben—despite his moral descent, and maybe even because of it.

The film that is named for him gives Ben everything he wanted. It asks basically nothing of him in return, save for a lot of car-driving and flop-sweating. And: It turns Elaine into a stooge, robbed of reason and agency. (And that’s not even getting to the character of Mrs. Robinson—which, Team Ebert again.) The violin the audience is being asked to play here is so very, very small. And as much as I appreciate The Graduate, still, on a scene-by-scene and frame-by-frame basis—on that level, it is magisterial—overall, I couldn’t get over its Poe’s Law failings. The movie didn’t sell me as satire. But if it’s not satire … what is it?

LaFrance: Maybe I’m going too easy on Mike Nichols, the director, but I always figured the Robinson women (not to mention Mrs. Braddock) were so one-dimensional because we’re seeing the events of the film totally through Benjamin’s eyes and delusions. Consider again the famous “April Come She Will” montage: all of those tight shots on Ben’s face; and the fact that we pretty much only see Mrs. Robinson’s torso, in various states of undress, to mark the passage of time; and then the view of his mother in the final shot of the sequence, where she’s basically indistinguishable from Mrs. Robinson. (Of course you’re right that Elaine is absurdly and unreasonably passive, but I have to say Katharine Ross’s eyelashes are legit amazing.)

There’s a story I once read about a dinner-party exchange between Nichols and his long-time comedic partner Elaine May. She apparently asked, off-handedly, something like, You know what I can’t stand about God? And Nichols replied, without pausing, That he hates arrogance but doesn’t mind cruelty. I always remembered that line because it’s pithy, and also because it’s pure Benjamin Braddock: hates arrogance, but doesn’t mind cruelty. Resents the establishment, and fights back by conforming. And just like the rest of The Graduate, if it weren’t so sad, it’d be hilarious.

Orr: I find myself caught between your two poles of outright Graduate-love and Ebert-y disdain. I find the first two-thirds of the movie genuinely brilliant but, as noted, feel it falls apart badly in the final act—like you, Megan, largely because nothing Elaine Robinson does makes a lick of sense. You’re right, Adrienne, that the movie is told almost exclusively from Ben’s perspective, but that doesn’t prevent Mrs. Robinson from being a complex and fascinating character.

Elaine is just a dud.

Megan went through most of the particulars, though I’d add that Elaine contemporaneously tells not one, but two men—neither of whom seems remotely appealing—that she “might” marry them. Then ultimately she lets her parents make the decision for her (what is she, 9?) before impulsively abandoning her now-husband for a glass-banging lunatic who she knows slept with her mother. She seems devoid of even the slightest hint of agency, literally inclined to do whatever the last male character to speak to her tells her to do. And, no Megan, I think there’s zero chance that this was a deliberate bit of sexual satire.

Not to throw stones unnecessarily, but the failures of the character are exacerbated by the fact that Ross is simply not a good actress. She lucked into roles in two classic films (The Graduate and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid two years later) and two other culturally relevant ones (1975’s The Stepford Wives and 1976’s Voyage of the Damned), but she’s not particularly good in any of them. Ironically, while we’re on the subject of marital indecisiveness, Ross had four brief marriages during the period of her semi-stardom. Happily, she seems to have finally gotten it right in 1984 by marrying Sam Elliott, whom she’s still with. Perhaps there’s hope for Elaine after all.

Garber: Chris, you mentioned that Mrs. Robinson is “a complex and fascinating character,” and, YES, I so agree. To me, she redeems this movie in so many ways. Even though, like you said, Adrienne, so much of her character, just like so much of Elaine’s character, is filtered through Ben-o-vision … there’s still such richness that comes through. And in some part, I think, precisely because of the psychic distance the movie imposes on her.

Mrs. Robinson has such a feline quality to her: She moves so quickly, so intentionally, so efficiently. She swathes herself in leopard print, and tiger print, as if she were trying to summon the spirit of the creatures in question. (According to Wikipedia, which would totally never lie about such things, the use of the term cougar to suggest an older woman who dates a much-younger man didn’t come about until this century; I wonder whether the deeper roots of it, though, aren’t in Mrs. Robinson and her jungle-feline-tastic loungewear.) There’s something so … I don’t know, precarious about her character. She threatens. She lurks. She seethes, quietly. One of the things I appreciate so much about Bancroft’s performance is how deftly she strikes a balance between coolness and ferocity: There’s so much simmering beneath that self-controlled surface. So much anger. So much pain. So much sadness that she takes out not just on her husband, and not just on her daughter, but also on “Benjamin.”

And, speaking of that! One of the things that struck me in a way it hadn’t quite before was how deeply predatory Mrs. Robinson is toward Ben—especially at the beginning of their (romantic) relationship. (And that’s doubly striking, of course, and sadly ironic, given that Hoffman himself has been accused of sexual assault.) After Ben drives Mrs. Robinson home from his party, he tries to leave; she will not let him. He resists; she ignores him. She slams the door. She takes her clothes off. He resists again. She insists. It is not necessarily played as an interaction that is deeply uncomfortable; it struck me as deeply uncomfortable nonetheless. We said in the intro to this conversation that Ben and Mrs. Robinson have a “lust-based affair,” but this is another question I had about the movie: Were we really witnessing lust? Perhaps that was Nichols’s and the other filmmakers’ intention, that Ben was successfully seduced; for me, though, I got no sense at all of (sexual) chemistry between Hoffman and Bancroft, and thus between Ben and Mrs. Robinson. Their affair felt to me like an ongoing case of mutual exploitation. Two sad people, using each other. A time bomb, ticking.

And, of course, that could be the point, as well: an affair that is profoundly cynical, but—both despite and because of the cynicism—cinematically interesting.

To return to the generational tensions you guys discussed above, one of the things I find most fascinating about Mrs. Robinson is how aligned she and Ben ultimately are in their anxieties. Ben, here, is being confronted with a kind of death: of youth, of possibility, of freedom. So, too, is Mrs. Robinson—not with a physical death, necessarily, but with the death of her purpose, her value, her identity. She lived during a time when upper-class women were appreciated primarily as wives and mothers, when little more was expected of them than to marry and procreate; as the film plays out, though, her daughter leaves for college, and for a life of her own. Her marriage is stifling. She has, seemingly, no job, no hobbies, no friends, nothing but an empty house that she fills with meaningless symbols of distant wildness. She is rich, and, at the same time, she is robbed—of the stuff that makes a full life and a full person. The film never reveals her first name; she is merely “Mrs. Robinson”: a name, but not a self. What’s that you say, Mrs. Robinson? The song, gah, never bothers to find out.

Friedersdorf: You’re so right, Megan, that the complexity of Mrs. Robinson is among the film’s strongest features—and one accomplished so efficiently! Is there any more efficient dialogue-driven scene in any film than Ben’s failed attempt at pillow talk, which begins with Mrs. Robinson declaring that she has no interest in talking about art and ends with her admission that she majored in the subject?

To me, the film is impossible to imagine without Bancroft—and as impossible to imagine with Robert Redford cast as Benjamin Braddock, which almost happened. The alternative Elaine Robinson was Candice Bergen. Chris, maybe you’d have liked her better? But I’m going to undertake a brief defense of the film as it was made, granting that Elaine’s motivation was obscure enough to be a weakness, but defending the last third of the film nevertheless.

Begin with what I take to be the most charitable reading of Elaine: Nichols is showing us the character through Ben’s eyes, as Adrienne suggested—and for that reason, those parts of the story almost require her to be devoid of personality, because Ben isn’t ever seeing her for who she is—he sees in this person he barely knows the woman of his dreams because that’s what inexperienced, self-centered, insecure 21-year-old men do amid hopeful, anxious, romantic fantasies about being destined for a “different” future.

Had Ben ever seen the real Elaine you wouldn’t have that moment on the bus, at the ending, when it suddenly occurs to Ben that he doesn’t actually know Elaine at all.

But we do.

That late scene in church is when the audience gets its best glimpse of Elaine, and in it her actions make more sense, I think. We don’t really know how long she’d dated Carl or what their relationship was like (though one surmises “the old makeout king” wasn’t unlike Mr. Robinson and his Ford). But we do know she was raised by Mrs. Robinson. We know how assertive, acerbic, manipulative, quick to anger, and vindictive Mrs. Robinson could be. And that she was an alcoholic.

Imagine being raised by someone like that—or check out any website for adult children of alcoholics:

Many of us found that we had several characteristics in common as a result of being brought up in an alcoholic or dysfunctional household. We had come to feel isolated and uneasy with other people, especially authority figures. To protect ourselves, we became people-pleasers, even though we lost our own identities in the process … We preferred to be concerned with others rather than ourselves. We got guilt feelings when we stood up for ourselves rather than giving in to others. Thus, we became reactors, rather than actors, letting others take the initiative. We were dependent personalities, terrified of abandonment, willing to do almost anything to hold on to a relationship in order not to be abandoned emotionally. Yet we kept choosing insecure relationships because they matched our childhood relationship with alcoholic or dysfunctional parents.

Of course Elaine barely stood up for herself on her first date with Ben, quickly forgave him, and acceded when her parents pressured her to marry Carl. She’d spent her whole life avoiding conflict, trying to please, going along to get along—and hatred of having to do so finally erupted in a spectacular at-the-altar rebellion. What strikes me about that scene in the church is that Elaine’s decision to run off with Ben has less to do with him than the reaction his appearance evokes in others: the hatred on the faces of her mother and father, and her horror-struck realization that Carl’s face is warped by the very same expression.

Elaine didn’t run to Ben—she ran away from a relationship with her mother so broken that she disbelieved her claim that she’d been raped, and from a marriage like that of her parents. Ebert was wrong twice. He shouldn’t have been rooting for Ben or Mrs. Robinson. We all should’ve been rooting for poor Elaine all along!

Finally, about that ending: The Graduate has a fantastic ending! Yes, the genius “What have we done?!” moment on the bus—but also the climactic scene in the church that preceded it, with a crucifix wielded to block the door; and the scene before that, with so much information conveyed in the faces of Elaine and her parents; and the moment before that, when Ben seemed to have arrived too late.

All that happened in the final third!

I admit that, more than most people, I am a sucker for sun-kissed footage of semi-suspenseful drives up and down Highway 101, which could be skewing my assessment here. But I submit that many folks remember liking The Graduate more on first viewings, when revisiting it years later, because they’ve forgotten the suspense and fun of seeing the film without knowing that final sequence.

What do you think, readers? Your thoughts on The Graduate are welcome, especially if you saw the film at different stages of life, or in late 1967 or 1968 and can speak to how it was received by the first generation to see it. Email conor@theatlantic.com and note if you don’t want your name used if I publish an excerpt.