In 2017, almost 50% more short story collections were sold than in the previous year. It was the best year for short stories since 2010. Booksellers are reporting a surge in popularity for the form, commentators note publishers are buying more collections and issuing them with greater care and enthusiasm; in December the newcomer Kristen Roupenian cut five- and seven-figure deals in the UK and US after her New Yorker story “Cat Person” went viral. On top of all that, collections are being reviewed more than ever before, the Sunday Times EFG short story award (worth £30,000) has received its highest ever number of entries and the BBC national short story award continues to grow in popularity. We are experiencing the renaissance of the short story form, right?

Wrong; which isn’t to say 2017 wasn’t a good year for the short story – it was, but the “renaissance of the short story” story is an old one that is rolled out year after year. Does that matter? I think it does. By getting caught up in this recurring phantom narrative, and dwelling on press release froth rather than the work being produced, we spurn the opportunity to talk about short stories in a way that might actually deepen how they are understood and engaged with by readers.

The Times Literary Supplement reflected in 2012 that the short story “has perhaps never been more alive”. In 2013 the New York Times announced that short stories were “experiencing a resurgence”. That same year the Irish Independent informed us that the short story was enjoying “a welcome renaissance”, which had become a “powerful renaissance” by the time the Spectator identified the trend in 2016, just as the Daily Telegraph almost simultaneously asked: “Has the short story come of age?” This was a surprising question, given that the same paper had bullishly announced the form’s “irresistible rise” two years earlier, and the year before that noted it was “finally getting the accolades it deserves”. Needless to say, all these restorations took place after “decades of neglect”. But how can the short story ever have time to wither, given the frequency of its rebirth?

Plodding through these random explosions of joy, the short story continues to exist with or without the glare of widespread attention. Each year, good collections are published; some are noticed, some are not. Most don’t sell many copies (a debut collection from one of the major publishing houses might have a print run of 3,000, with little expectation of a reprint). When a collection is fortunate enough to be reviewed, it will very often be a discussion not just about the book but also the form generally.

This is understandable: given the ubiquity of the renaissance narrative, reviewers would be neglectful journalists if they didn’t. And so the sense we are always experiencing some kind of “moment” for the short story is perpetuated, and they are prevented from simply being short stories in the way that novels, generally speaking, are allowed to be novels.

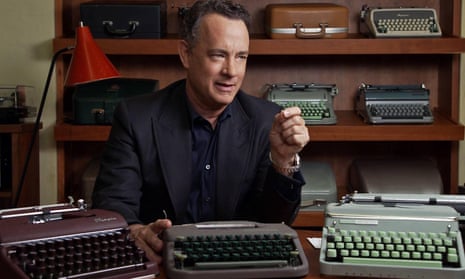

But if we aren’t living through a renaissance of the short story, how to explain those booming sales figures? Let’s break them down. Collections by Tom Hanks, one of the world’s biggest film stars, and Jojo Moyes, one of its bestselling authors, represent 22% of that total: £1.3m in sales.

Only the most Panglossian observer could believe the tens of thousands of readers who bought Tom Hanks’s Uncommon Type, or even the sellout audience of 2,900 who attended his reading at London’s Royal Festival Hall, will all convert into committed readers of the short story. Likewise with Moyes. These books sold because of who wrote them, not because of what they are. In Moyes’s case, you could say fans bought her book in spite of it being a story collection; Still Me, her third Louisa Clark novel and the current bestselling hardback fiction title in the country, will doubtless outsell it many times over. Remove Hanks and Moyes from the equation and yes there has been an uptick, which is great news – but not the 50% year-on-year sales surge the papers are talking about.

That still leaves Roupenian, however, and those enormous deals she secured on the strength of a single short story: just over $1m in the US, and just under £100,000 in the UK. Here again, a closer look is revealing. The deals were triggered by the wild success of a short story about female/male sexual relations that caught the mood of the #MeToo movement, but the deals were for two books: the story collection You Know You Want This and a novel. I don’t know the precise breakdown, but I would be very surprised if the majority of those sums weren’t for the novel. Certainly two of the two-book contracts I signed last year apportioned more of the advance to a novel that didn’t exist than to Mothers, the short story collection that did. (There, sadly, the similarities to Roupenian’s deals end.)

Why should this be the case? Because compared with the novel, short stories are a minority interest. On one level, all these recursive announcements of the renaissance of the form amount to is PR: if short stories are made to seem like “a thing”, maybe a few more people will buy collection X or Y. The fallout from this approach is that short story writers must address endless questions about The Short Story as opposed to short stories. What is a short story? Why should we read them? Are they coming back? Did they ever go away? And on and on and on.

I would love it if we could forget the form for a little bit and focus on the work instead, because 2017 really was a vintage year for collections: Ottessa Moshfegh’s bleak and brilliant Homesick for Another World; Jenny Zhang’s Sour Heart, packed with hilarious and moving stories about Chinese and Taiwanese immigration to the US; the hypnotic meditations of László Krasznahorkai’s The World Goes On; Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-busting Her Body and Other Parties (a 2017 National Book award finalist in the US); the sad lives and humane observation of Akhil Sharma’s A Life of Adventure and Delight; the compelling enigmas of Darker With the Lights On by David Hayden; the thrilling streams of consciousness described in Eley Williams’s Attrib.; the disturbing alternative realities of the newcomer Camilla Grudova (The Doll’s Alphabet), and of Sarah Hall (Madame Zero); the grimly fierce invention of June Caldwell’s Room Little Darker; and the powerfully moving stories of dislocation in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees.

These are all exceptional books that deserve space on any serious fiction reader’s shelves. But you know what? Pick any year and you’ll find some great story collections were published then, too; sometimes even more than in 2017, sometimes less, but enough to suggest a healthy genre.

Like any art form the short story needs attention, of course that’s true; but if you really care about it then please, don’t call it a comeback

Chris Power’s Mothers is published by Faber. To order a copy for £8.50 (RRP £10) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion