I spent the summer of 1977 trekking through the mountains and rivers of the Brooks Range—in what was then called the Arctic National Wildlife Range, and in the country that would soon come to be known as Gates of the Arctic National Park. In my backpack I carried two slim books: Winter News by Alaska’s great poet John Haines and Desert Notes by Barry Lopez.

Within a few years, both of these men would become close personal friends of mine. But in that summer, my 24th, I knew them only through their writing. I was captivated by the intensity of their words and by the striking similarity of their visions, drawn from such apparently different landscapes. In time, Lopez would underscore those affinities with Arctic Dreams, a major volume that greatly expanded my understanding of the circumpolar North.

But reading those two earlier books in the mountains of the Arctic that summer helped me begin to discover my own nascent vision of music grounded deeply in place.

The landscapes of the North have profoundly shaped who I am and what I do. For almost 40 years I lived in Alaska, and I imagined I would spend my entire life there. Yet even as a younger man I sometimes said that if I ever left Alaska, it would be for the desert. Now, in my sixth decade, this has happened.

I still think of Alaska as my home. And leaving home doesn’t feel like any sort of renunciation of the North. In fact, it doesn’t feel like that much of a change. As I’d sensed all those years ago, the tundra and the desert aren’t as different as they might seem. Climatically speaking, the Arctic is a desert. Both landscapes have few if any trees. Both have enormous skies and extraordinary qualities of light. And for me the feeling of being on the tundra or in the desert is remarkably similar.

Throughout my years in Alaska, I dreamed of a new music drawn from the light, the air, the landscapes, and the weather of the North. Now as I’ve begun to learn the landforms, the light, the weather, the plants, and the birds of the desert, I’ve begun to dream of music that resonates with these extraordinary landscapes.

Become Desert is a 40-minute symphonic work that completes a trilogy that I didn’t set out to write. In all three of these works, space is a fundamental compositional element. I’m not speaking only of poetic or metaphorical space, but also of the physical, acoustic, and volumetric space of the musical ensemble and the place in which the music is heard.

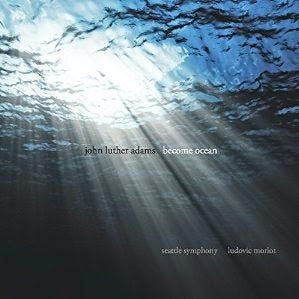

In Become Ocean, a full symphony orchestra is deployed in three different ensembles separated as widely as possible. Each of these groups has its own distinctive instrumental and harmonic coloration, and each moves at its own tempo.

Become River is scored for a smaller orchestra, turned upside down. Rather than their usual position near the edge of the stage, the violins are seated far upstage and elevated, and the entire ensemble is arranged on a decline from there. Over the course of 20 minutes, three different musical streams moving at different speeds flow downstream, from high sounds to low—taking the listener on a musical journey from the headwaters to the edge of the sea.

Become Desert is the same length as Become Ocean. However, this new work encompasses an even larger musical space. Five different ensembles moving at five different tempos are stationed around the audience.

For decades now, one of the most fundamental questions I ask myself when I begin a new composition is: “What are the instruments?” With Become Desert, this became two questions: “What are the instruments? And where are they located?”

For a long time, I pondered the floor plan, the physical deployment of the instrumental and vocal choirs within and around the performance space. Ultimately, I decided to disperse the strings all over the stage, with four harps and four percussionists interspersed among them.

The other four choirs are elevated on high risers, in balconies, lofts, or boxes around the performance space. Upstage, a choir of 16 woodwinds and a percussionist playing crotales (antique cymbals) is elevated as high as possible above the strings. A choir of eight horns and a percussionist playing chimes is elevated on one side of the space. A choir of four trumpets and four trombones and a percussionist playing chimes is elevated on the other side of the space. And a choir of singers and handbells is elevated at the rear of the space.

Only when I arrived at this layout, only when I could begin to hear this sonic space in my mind, was I ready to begin writing the score.

You might wonder why this desert space is even larger than my musical ocean. It has to do with the location of the listener. In Become Ocean we’re out on the water, riding the tides and the musical waves as they rise and fall. In Become Desert we are immersed, not in water but in stillness, space, and light.

In the desert we don’t simply look at the light. We swim in the light. Here, as Octavio Paz observes: “That which is not stone is light.” Here you can “close your eyes and listen to the singing of the light.” It was this image of listening to the light that made me feel this music needed to include human voices. The chorus in Become Desert sings a single word throughout: luz (the Spanish word for “light”).

Like the tundra, most deserts are places in which there are few people. It’s true that this is part of the reason I’m drawn to these landscapes. But for me, the essence of the desert is not absence. It is presence.

In the space and stillness of the desert, we listen for that singing of the light, and for the many voices of the wind unbroken by little more than stone and distance. In the desert there are moments when, as Paz says, you sense that “there is no one, not even yourself.” Those moments are invitations to surrender our expectations, to lose ourselves in listening to the music of the present.

Most of us these days live lives in which we’re trying to hear less. In a world filled with unwanted sound, we use our earbuds to shut ourselves off from the world, retreating into our own private aural caves. In the desert, we are challenged to open our ears again, to come out of our caves and listen to the never-ending music all around us. For ears accustomed to constant stimulation, this can be challenging, even unnerving.

As dramatic as the landscape may be, the music of the desert is subtle. At first it can seem static and monotonous. But the longer we listen, the more we begin to notice change. Our ears become attuned to the slightest shifts in the breeze. The brief song phrase of a single bird can resonate in our mind’s ear for a very long time. We may even begin to hear the low hum of the earth itself.

In the desert, it’s difficult to perceive scale. This is true not only for our eyes, but also for our ears. Is that a motor somewhere far off? Or is it the wing beats of a nearby bee? Am I hearing human voices just beyond the field of my vision? Or is that the low mumbling of hidden water running over stone? Is that the sound of distant thunder? Or is it the rumble of a breath of wind passing over my ear?

Somewhere I read that the ancient Greeks regarded music as the child of memory and weather. Like most of us these days, I’m deeply concerned about climate change. But if climate is what we expect and weather is what happens, then I seem to be more interested in the weather of music.

It’s impossible to escape our memory of what has happened in the past, and it’s difficult to let go of our expectations of what might happen in the future. Yet listening to the music of the desert—however faint, however uneventful it may seem—I hope to lose myself in the fullness of the present moment.

This is what I want for myself. It’s also what I want for a listener to my music. I’m not interested in telling you about my experience of the desert. Rather, I hope that you may have a moving experience that is uniquely your own.

From time to time, speaking of Become Ocean, people have asked me: “Which ocean is it?”

My answer to that question is always the same: “Your ocean.”

My own deserts are in Mexico and in South America. However, Become Desert is not a musical painting of any particular landscape. This music is, I hope, its own inherently musical landscape that extends beyond the place in which it was composed. In the ears and the imagination of the listener, I hope it becomes a private desert of your own.

Living in Alaska for much of my life, I’ve experienced firsthand the accelerating effects of anthropogenic climate change on the tundra, the forest, the glaciers, the plants, animals, and people of the Far North. While composing Become Ocean, I was haunted by the image of the melting of the polar ice and the rising of the seas.

Now, in my new home, I’ve become aware of a very different manifestation of global warming—desertification. Wildfires in California, the rapid evaporation of Lake Poopó in the Bolivian altiplano, and deep droughts in the Sahel of Africa and in large parts of Australia are signs of what is to come. As human population continues to explode, vast regions of grazing and agricultural land all over the earth will soon become desert.

I find myself pondering more deeply the observation attributed to François-René de Chateaubriand: “Forests precede civilizations, and deserts follow.”

Become Desert will make its world premiere with the Seattle Symphony in March.