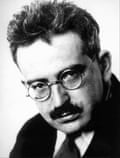

In June 1940, with Nazi troops on the verge of invading Paris, German-Jewish exile Walter Benjamin was preparing to leave the city. One of the leading European intellectuals of the 20th century, Benjamin was unable to acquire the necessary documents that would have made it possible for him to escape through the port city of Marseille. Instead, he joined other refugees trekking through the mountains into Spain, making their way to Lisbon where they’d fly out. Slowing Benjamin down was a heavy black suitcase, which contained a manuscript. Speaking to another traveller, Benjamin described the contents as more valuable than his own life.

In the border city of Portbou, Benjamin was informed by Spanish authorities that he would have to go back to France. That night, he swallowed 31 tablets of morphine that he had brought with him for a heart ailment. After his suicide, however, there was no trace of the black suitcase. The manuscript has never been recovered.

This story and other tales of disappeared books is recounted in Giorgio van Straten’s recent work, In Search of Lost Books. Among these lost works are those by Nikolai Gogol (Parts II and III of Dead Souls, which he burned); Sylvia Plath (a novel called Double Exposure which disappeared after her death); Lord Byron (his personal memoir, which his family had burned to protect his reputation) and Ernest Hemingway (an entire suitcase of early work, stolen from a train at Gare du Lyon).

For bibliophiles like me, the knowledge that these works once existed and are now gone evokes something akin to pain. Van Straten writes: “There is a quotation from Proust: ‘To release that fount of sorrow, that sense of the irreparable, those agonies which prepare the way of love there must be … the risk of an impossibility’. I think that passion for a lost book, often like love for a person, arises from the impossibility of reading it.”

In his book, Van Straten distinguishes between missing and lost works. If a manuscript is missing, there remains the hope that it was misplaced in an archive, waiting to be discovered. But with lost works – such as the novel Malcolm Lowry spent nine years working on, which went up in flames when his cabin burned to the ground – no hope is still possible. Yet it’s also clear that Van Straten still searches for lost books, even as he recognises the futility of it. He likens the search to his childhood notions of the quest, to his longing to be “the hero who will be able to solve the mystery”.

A lost book is also different from one that was never written; a work that existed creates what Van Straten calls a “void”, which we fill with ideas of what might have been. Did it answer an unanswerable question? Did it achieve perfection? Was it a work of art, that we are lesser beings for having lost?

Like Van Straten, I am fascinated by these book-shaped holes in the intellectual firmament. When I was a student, my greatest fantasy was that I would some day find a book or manuscript previously thought lost, or solve a historical mystery. The idea of a hunt resembled the sense of adventure I felt every summer as a child with my cousin, when the two of us would explore the beach, searching for pirates’ treasure.

Benjamin may be the person to explain the “authenticity” that lost works are thought to possess. In his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he posited that it is the ubiquity of mass-produced printed objects that causes us to lose our sense of awe when we hold a paperback in our hands. Is a book less special because we can all own a copy? It’s the same sense of disappointment that many visitors to the Louvre have remarked upon: after you’ve seen so many reproductions of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, what to make of the small painting that hangs on the museum’s wall?

One person who has experienced the frisson of excitement that comes from having contact with unique texts is Christopher de Hamel, whose Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts presents a treasure house of manuscripts that he has been able to study. The illustrations from the Book of Kells and the book of hours of Jeanne de Navarre – among others – are breathtaking, and de Hamel presents both the stories behind the manuscripts, but also his own reactions to them.

Why does a manuscript hold more value to us than a published, finished product? “It depends on what you want to experience,” says de Hamel. “It is quicker to read Chaucer in a modern edition. But that personal thrill of touching and turning the pages of the original is incomparable. We all want to touch hands with history.”

Does the Book of Kells lose any of its allure when a mass-produced paperback version is available to buy just feet away, in Trinity College Dublin’s gift shop? No, says de Hamel: “There are things you’ll see in an original manuscript that even a microfilm or digitised surrogate cannot convey – drypoint glosses, erasures, sewing holes, underdrawing, changes of parchment, subtleties of colour, loss of leaves, patina of handling – even smell and touch and sound, which can transform knowledge and understanding of the text when its scribes made it and first readers saw it.” So, when we mourn lost manuscripts, it’s not just over the disappearance of words, we are also losing an understanding of the process of their creation – the author’s scribbles, their hasty additions, their fraught deletions.

There are many lost books that de Hamel hopes to one day see: “The Book of Kells had more leaves in the 17th century than it does now. Are they somewhere in someone’s scrapbook? The 12th-century Winchester Bible, perhaps the greatest English medieval work of art, had a number of miniatures cut out, possibly as recently as the 20th century: some, at least, probably do exist. I really, really want to find one before I die.”

As painful as it is to contemplate what became of them, I find myself returning to Van Straten’s argument that lost books are like lost loves. Just as Tennyson wrote in In Memoriam (“Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”), knowing that these works once existed is oddly comforting, even if they’re never found or restored. The space for that knowledge is not empty – it is a void. As Van Straten writes, “By the end of the voyage I had realised that lost books possess something that others do not: they bequeath to those who have not read them the possibility of imagining them, of telling stories about them, of reinventing them.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion